Chapter 4b: Environmental Waste Management Policy Statements

“ESG looks at how the world impacts a company or investment, whereas sustainability focuses on how a company (or investment) impacts the world.”

-Brightest.io

Objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers will be able to:

- Explain the significance of having a comprehensive waste management policy for businesses and its impact on sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

- Avoid common barriers that prevent consumers from adopting sustainable behaviors to craft messages that address and overcome these barriers.

- Create human-centric sustainability messages that effectively communicate the value of sustainable practices to consumers and build trust.

Introduction

Businesses may adopt policy statements to reflect their unique business situation and philosophy. [1] Common statements are similar to the following:

Example

____________ (your company name) is committed to protecting the environment, the health and safety of our employees, and the community in which we conduct our business. It is our policy to seek continual improvement throughout our business operations to lessen our impact on the local and global environment by conserving energy, water and other natural resources; reducing waste generation; recycling; and reducing our use of toxic materials. We are committed to environmental excellence and pollution prevention, meeting or exceeding all environmental regulatory requirements, and to purchasing products which have greater recycled content with lower toxicity and packaging, that reduce the use of natural resources.

Such a statement is a good start, but is too vague the way it is. It could use more quantifiable information as well as the following:

- Maximize post-consumer recycled content.

- Minimize packaging and other wastes.

- Minimize toxicity.

- Mention what is durable and reusable.

- Add what is locally available to minimize transportation.

- Add anything made from sustainably produced materials.

- Mention if anything is compostable or biodegradable.

- Conserves energy, water and other natural resources.

More Specific Example

The goal of this policy is to ensure that products and services purchased or contracted for conform to the goals of our company’s environmental policy. We will strive, where feasible, to purchase environmentally preferable products and services to meet the company’s office and operational needs. We will also favor suppliers who strive to improve their environmental performance, provide environmentally preferable products, and who can document the supply chain impacts of their efforts.

Wherever possible, purchasing decisions will favor products and feedstocks that:

- Reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

- Are made with renewable energy.

- Reduce pollution from all discharges (releases to air, water, and land).

- Reduce the use of toxic materials hazardous to the environment, employees and public health.

- Contain the highest possible percentage of post-consumer recycled content.

- Reduce packaging and other waste.

- Are energy efficient.

- Conserve water.

- Are reusable and/or durable.

- Minimize transportation (local sources, concentrated products).

- Serve several functions (examples: copiers/printers, multipurpose cleaners) to reduce the number of products purchased.

Environmentally preferable products and services that are comparable in quality to their standard counterparts will receive a purchasing preference. In situations where the most environmentally preferable product is unavailable or impractical, secondary considerations will include production methods and the environmentally and socially responsible management practices of suppliers and producers. Environmentally preferable purchasing is part of our long-term commitment to the environment. By sending a clear signal to producers and suppliers about this commitment, we hope to support wider adoption of environmentally preferable products and practices. [2]

Understanding Barriers to Writing Waste Statements

Recognizing potential obstacles is the second stage in creating a behavioral communication strategy. Perceptions or assumptions about the unattractive behavior are likely to be the main reason of hesitation when a new habit is initially suggested. After the habit such as composting is well-established, the primary obstacles will probably change to those that organizations really face when trying to gather food scraps. Reviewing the obstacles encountered at every stage will optimize help readers embrace the behaviors required for the entire implementation process. UK research [3] identified the following barriers.

- Belief: People think separating food scraps is too hard and others won’t adopt it.

- Attitude: People don’t trust that the food scraps will actually get processed.

- Attitude: People think food scraps can be smelly and attract vermin (the ‘yuck’ factor).

- Knowledge: People don’t know the issues of food waste in landfill and the benefits of food scraps recycling.

- Habit: A small subset of people are already composting or worm farming and don’t believe they need another system.

- Physical: not having free or easy access to (more) liners when provided benchtop bins

Aotearoa research [4] with those not using an available food scraps collection found the most common reported reasons for not participating in the collection were:

- physical – dirty or smelly

- physical – flies and pests (in kitchen and outside bin)

- habit – already compost

- belief – not having enough food waste to make it worthwhile.

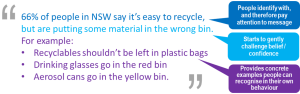

An example in the image below shows that people identify with the statistic so they pay attention to the message, then they are introduced a fact that gently challenges their belief or confidence, and then are provided tips with concrete examples so readers can recognize their own behavior. The statistic says “66% of people in NSW say it’s easy to recycle, but are putting some material in the wrong bin.” Then “For example, recyclables shouldn’t be left in plastic bags, drinking glasses go in the red bin, and aerosol cans go in the yellow bin”:

Communication Tips on Discussing Waste Management

The Ministry for the Environment (2023) has the following advice in its public document, Best practice communications for waste minimisation: A guide to support effective behaviour change within households. [6]

Generic Waste Management Communication Strategies [7]

The New Zealand Ministry of the Environment (2023) gathered helpful message ideas that may aid in writing about one’s waste management and encouraging others to handle waste more effectively by using general behavioral understanding, even without officially performing formal research on specific behavioral obstacles. [7]

Based on typical obstacles to participation and proper sorting, the Library’s following insights have been proven to be useful in promoting curbside recycling behaviors.

Generic guide to choosing behavioural insights from the Library of Behavioural Insights

Insights to make behavior (seem) easier

| Insight | Definition and example |

| Commitments | Encouraging a declaration to perform the behaviour, often publicly “I took the ‘Recycle Right’ pledge.” |

| Feedback | Providing information to reinforce, correct or modify the behaviour “60% of homes on Beach Road collect all their food scraps. The average for the region is 50%.” |

| Instructional | Providing clear instructions or guidance on how to perform the behaviour “Here are the food scraps you can put into your green bin…” |

| Prompts | Providing reminders or cues to perform the behaviour at an appropriate time ‘Eat me first’ stickers for food containers. |

| Self-efficacy | Increasing confidence in ability to successfully perform the behaviour “Simple swaps you can make to reduce single-use plastic…” |

Insights to make behavior more attractive

| Insight | Definition and example |

| Consequences | Indicating what will happen if the behaviour is performed or not performed “Recycling correctly helps create employment and supports the local economy.” |

| Emotions | Evoking specific emotions that motivate the behaviour “Don’t be a bad apple: check dates and eat older food items first.” |

| Outcome efficacy | Increasing confidence that the behaviour will achieve the desired outcome “Every food scrap counts.” |

| Social norms | Presenting the behaviour as common or socially acceptable “Over 85% of New Zealanders already recycle packaging. It won’t be long before we match that with food scraps.” |

Word Choice

When discussing sustainability in business, it is essential to specify the relevant collection channel, such as “kerbside recycling” or “kerbside recyclable,” rather than vague terms like “recyclable at store.” This clarity helps people understand that recycling occurs through various collection channels and not everything recyclable belongs in the kerbside recycling bin.

Avoid highlighting the scale of the problem, as this can create a negative social norm that food waste is normal and leave people feeling powerless to make a difference.

Use the term “soft plastic packaging” generally when describing soft or flexible plastic to households, as it aligns with existing product stewardship schemes and packaging labels. Initially describe it in full to familiarize people with the term, and subsequently remind them of its meaning with brief descriptions in the body of the text.

Emphasize the “single-use” aspect in messaging to prevent confusion with the incorrect belief that “all plastic is bad.” Broaden the focus from single-use plastic to single-use items of any material to emphasize behaviors that reduce waste rather than just substituting one material for another.

Communication Tips on Handling Food Waste

When communicating changes to the list of eligible items, messages such as “Only these things are/will be accepted…” are necessary but insufficient to prevent contamination. These messages need to be supplemented with specific instructions about what is no longer accepted and alternative ways to recycle or dispose of these items, such as placing them in the rubbish bin.

Distinguishing between the inside container, like a “kitchen benchtop bin,” for daily food scrap collection, and the outside food scraps bin for weekly or fortnightly curb collection, helps people recognize the different behaviors involved in collecting and transferring food scraps.

Highlight a range of benefits to motivate food waste minimization. While financial savings are a key motivator, other influential factors include the quantity of waste, the effort and resources involved in food production, and the appeal of being organized. Messaging that emphasizes these aspects can effectively engage households.

Visual and Strategic Messaging

Use vibrantly colored photos in a flattering light to attract the attention of both highly and less engaged households. Avoid monochrome photographs and ensure the images are appetizing and seen as usable.

Using easily interpretable icons instead of photos for instructions is recommended, as photos of “old” food can raise concerns about messiness and smell, while photos of “good” food can evoke a sense of wasting good food.

When using images of fruit and vegetables past their best, make the future use of the food clear, such as showing over-ripe bananas being used to make banana bread. This helps engage less engaged households who might otherwise be alienated by images of food past its best.

Include images that include two or more people, as they are effective in drawing attention and emphasizing the positive social association of waste. Avoid images showing just “hands” or individuals on their own.

When using imagery that conveys the negative impact of single-use plastic, such as on wildlife, always accompany it with tangible and positive actions that show how people can make a difference. This approach avoids producing emotions like sadness or guilt, which can undermine behavior change.

Communication Tips on Behavior Change Strategies

When introducing a new service, make the desired behaviors as easy as possible to adopt before starting any behavior change campaigns. For example, provide appropriate benchtop bins and liners. Making it easy is crucial to achieving the new desired behavior, as communications alone cannot overcome physical barriers.

Design communications to be multilayered over time. Start by introducing and explaining the new service, followed by encouraging and reminding households, and supporting them in dealing with barriers.

Provide timely reminders to support new behaviors, as services like food scraps collections face the challenge of forming new habits among households. Maintain momentum by communicating strong social norms around uptake and approval and sharing local stories that highlight how individual actions make a difference at the community level.

Each communication should focus on a single call to action. A single key message is most effective, as two or more messages can lead to “cognitive overload,” making it harder for people to process the information.

Use prompts to support those already intent on changing their behavior or who find the desired behavior easy. Pair prompts with other strategies for those with low awareness of the issue or need. Design prompts to be kept and positioned where the desired behavior occurs, such as the kitchen, and focus on key instructions rather than slogans or motivating messages.

Remind people of the value in individuals taking responsibility for what they can do, despite perceptions of the scale of the problem or others’ behavior. Provide visualizations of the impact small actions can have and the multiplier effect when many people join together to reinforce this message.

Tips on What Not to Write

When discussing waste management, it is advisable to avoid using the term “food waste” as many individuals do not see themselves as contributing to food waste. [8] This term also carries connotations of food-related waste, such as tea bags, food-soiled paper towels, cardboard, and paper from fish and chips, which many food scraps collections do not accept. Instead, using the term “food scraps” can be more effective as it resonates with more people and focuses directly on the food items themselves. [9]

Avoid using images of plate waste and half-eaten food in your communications, as these visuals can be off-putting to your audience. Such images can evoke negative reactions and may discourage engagement with your overall message.

It is important not to highlight the scale of the problem, such as the volume of contaminated recycling going to landfill, in an attempt to create a sense of urgency or importance. This approach can inadvertently evoke emotions of fear, disgust, helplessness, and/or guilt, either intentionally or unintentionally. Emphasizing the magnitude of the issue may also suggest that doing the “wrong” thing is a social norm, thereby undermining individual motivation to make a positive impact.

Refrain from referencing issues like climate change, either explicitly or implicitly through mentions of emissions. Such references can make people feel powerless and skeptical about the effectiveness of their actions. Messages about climate change tend to be more distant and future-focused compared to messages about avoiding landfill and creating compost, which are more immediate and actionable. [10] As mentioned in a previous chapter, mentioning climate change or global warming in the US may also make readers think a business is making a political statement, which may work for or against its favor.

Do not treat resident concerns lightly or dismissively, even if they seem minor. Research in New South Wales found that many concerns households had before a new service began turned out to be real barriers once the service commenced. Show how individual actions matter and their positive impact, reinforcing the message that “Every little bit counts – even your small actions will make a big change!” [11] Instead, focus your messaging on positive information that validates and addresses these concerns, providing constructive and supportive communication.

|

Concern |

Dismissive message | Validating message |

| Sorting out food scraps will take lots of extra effort | “Sorting food scraps is easy” |

“We’re providing benchtop bins to make it as easy as possible” |

Commitments, emotions (positive), outcome efficacy and social norms (positive) have the strongest evidence of encouraging audience to change their behavior.

Positive consequences (benefits) suggest that a good outcome will arise from doing a desirable action or by not engaging in an undesirable actions. For example, “recycling lowers the costs of dealing with your trash” demonstrates a positive consequence, and “these savings can be spent on other more important services” shows a benefit to the individual.

Negative consequences suggest that a bad outcome will arise from an undesirable action or by not engaging in a desired actions. For example, “wasting food is costing more than you think” demonstrates a negative consequence and “New Zealand households could save an average of $__ per week by making better use of the food they buy” shows a benefit to the audience/individual.

(IMAGE PLACEHOLDERS)

Other examples of consequences in messages include the following:

- Authority. Phrases such as “Contaminated bins won’t be collected, so make sure you are recycling right” convey the idea that someone in a position of power is watching behavior and rewarding good behavior while punishing bad behavior.

- Environment. Sayings like “…by reducing single-use plastic, you can help prevent harm to vulnerable species like…” indicate that good behavior will protect the environment while bad behavior will damage it.

- Financial. It is implied in messages that good deeds will bring you money while bad deeds will cost you money (e.g., “Correct recycling reduces costs to your council and therefore you”).

- Social. It is implied in messages that good deeds will benefit society, while bad deeds will harm it For example, “Put all of your food scraps in the green bin – your local farmers will thank you.”

Instructional messages teach people what to do with waste and give them the know-how they need to successfully participate in the desired behavior for managing waste. The following are some examples of instructional techniques for waste-related behaviors:

- details on what can and cannot be recycled;

- advice on how to get over recognized obstacles (such lowering the “yuck” factor associated with collecting food scraps);

- product ideas (e.g., to limit usage of single-use plastic)

- exchanging straightforward guidelines, practical advice, or tactics (e.g., how to keep food fresh for longer).

When providing instructional messages on waste management, keep it simple and clear. Provide concise instructions and tips that are easy to understand. When explaining complex tasks, break them down into manageable steps or offer simple rules, using diagrams or demonstrations to illustrate correct actions. Tailor instructions to specific waste-related behaviors and the community’s current practices. For instance, emphasize ‘No’ items to reduce recycling contamination and ‘Yes’ items to promote food scraps collection. To encourage avoidance behaviors, make tips fun and social, ensuring they are easy and appealing to try. [12] Pair these instructions with behavioral communication principles like visual chunking and streamlining. Avoid overwhelming individuals with excessive information or complex instructions, as this can lead to cognitive overload. Use instructional messages that clearly define ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ actions. [13] For curbside recycling, using ticks and crosses with brief explanations and color codes can help convey the message quickly and clearly. [14]

To ensure effective communication in waste management, be mindful of the tone; instructions that are too obvious, insufficient, or generic can come across as patronizing or unhelpful, while authoritative messages like “Stop food waste” can provoke resistance. [15] Avoid promoting behaviors that seem impractical or inappropriate, especially in cross-regional or national communications, by targeting universal barriers or behaviors. [16] Emphasize effective actions in behavioral communications and make them appear easy to encourage behavior change. Highlight self-efficacy by focusing on controllable aspects of the problem and breaking down complex behaviors into small, simple steps. Enhance outcome efficacy by presenting effective alternatives, such as reusable items instead of single-use plastics or proper food storage methods to reduce waste.

Case Example: Staples® Recycling Program (“Program”) [17]

Terms and Conditions (“Terms”)

In an effort to reduce waste going to landfills, Staples has created the Staples Recycling Program which offers Customers the option of bringing in select items to Staples® U.S. stores, where it’s easy and rewarding to recycle. These Terms are an agreement between you (“Customer” or “you”) and Staples (“Staples”), and they govern your use of and participation in the Staples Recycling Program.

This Program is available to all Staples customers that bring in eligible recyclable items. Customers who are 18 years of age or older with a valid U.S. mailing address and a valid email address may enroll in the Staples Easy Rewards™ program to earn points for eligible recyclable items that they recycle with Staples. The Program applies to Staples U.S. stores only.

- Eligible Recyclable Items – The items that may be recycled at a Staples U.S. store (“Eligible Recyclable Items”) include ink and toner cartridges, a variety of electronics, SodaStream® CO2 cylinders, select batteries, select kitchen appliances, select writing tools, phone and tablet cases and paper. The list may change from time to time, and the complete list of eligible recyclable items at any given time will be available on the Staples website at: https://www.staples.com/stores/recycling. Some locations may offer additional recycling services. Items that are determined by Staples, in its sole discretion, to pose a health or safety risk will not be accepted. Staples does not accept products that are subject to a Consumer Product Safety Commission recall. The eligible recyclable items may be recycled free of any charge to the Customer. Customer may recycle up to seven (7) items per day. Certain eligible recyclable items are or may become eligible for points through the Staples Easy Rewards program. For more information on and terms related to Staples Easy Rewards, please visit: https://www.staples.com/easy.

- Electronics Recycling – Eligible recyclable items include a variety of electronic devices. Customers that recycle eligible electronic devices at Staples relinquish all ownership rights in the devices when they give them to Staples to be recycled. Additionally, Staples is not responsible for any data left on devices turned in for recycling. The Customer is solely responsible for removing data from their devices, and the Customer acknowledges that submission of a device for recycling is at the Customer’s sole risk. Customer further represents that Customer either: (1) is the sole owner of the electronic device and of any data that was on the electronic device before Customer deleted all such data prior to recycling; or (2) has permission to proceed with recycling from all other owners of the electronic device or of any data that was on the electronic device before Customer deleted all such data prior to recycling.

- Self-Service, In-Store Recycling – Some Staples stores offer self-service recycling kiosks which permit Customers to complete their recycling without the assistance of an associate. Customers are responsible for following the steps to ensure that any coupons or Staples Easy Rewards offers that would be awarded are attributed to them or to their Staples Easy Rewards account. Customers assume the risks when it comes to participating in the self-serve process in those stores.

- California Residents – In order to comply with the conditions of The State of California’s Electronic Waste Recycling Payment program, Customers in California will be asked to provide additional information to allow Staples to submit the information required for the recycling payment. The provision of this information is optional, and Customer’s refusal to provide such information will not preclude them from participating in this Program or in the Staples Easy Rewards program.

- General – For information on how we protect your personal information, see Staples’ U.S. Privacy Policy on staples.com. Staples is not liable for unclaimed, expired, lost or misdirected statements or other communications from Staples to the Customer or the Customer to Staples. These Terms are governed by the laws of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, without regard to its conflict of laws rules. Any Customer’s legal action against Staples relating to the Program may only be filed in the state and federal courts of Suffolk County, Massachusetts. If any provision of these Terms is found to be invalid or unenforceable to any extent, then the invalid portion shall be deemed conformed to the minimum requirements of law to the extent possible. In addition, all other provisions of these Terms shall not be affected and shall continue to be valid and enforceable to the fullest extent permitted by law. The Program is void where prohibited by law.

Staples reserves the right to modify, revise or cancel this Program, the Terms or any part of the Program at any time for all participants or for any specific participant without prior notice. Staples’ decision on whether a particular item can be accepted for recycling or is eligible for points through the Staples Easy Rewards program shall be final.

By participating in the Program, Customers agree to and are subject to these Terms.

What can’t be recycled in store:

- Air conditioners

- Floor-model printers & copiers

- Home & kitchen appliances

- Lamps & bulbs

- Large electronics

- Medical devices

- Records & record players

- Scissors & other blades

- Smoke detectors

- Televisions

- Vaporizers

- Wet-cell & heavy batteries (over 11 lb.)

Conclusion

In conclusion, effective communication strategies are essential for implementing successful waste management practices in sustainable businesses. By integrating the tips on word choices and tone, businesses can enhance their waste management practices and promote a culture of sustainability. This approach would not only improve operational efficiency but also foster a sustainable mindset among stakeholders, benefiting both the environment and society.

Key insights in the guide

| Insight | Definition |

| Commitments | Encourage a declaration to perform the behaviour, often publicly |

| Consequences | Indicate what will happen if the behaviour is performed or not performed |

| Emotions | Evoke specific emotions that motivate the behaviour |

| Feedback | Provide information to reinforce, correct or modify the behaviour |

| Intrigue and gamification | Evoke curiosity or a sense of mystery around the behaviour

Incorporate fun or game-like elements to increase engagement |

| Instructional | Provide clear instructions or guidance on how to perform the behaviour |

| Prompts and priming | Provide reminders or cues to perform the behaviour at an appropriate time

Expose images, ideas or information that can influence future responses or decisions |

| Self-efficacy and outcome efficacy | Increase confidence in ability to successfully perform the behaviour

Increase confidence that the behaviour will achieve the desired outcome |

| Social norms and social proof | Present the behaviour as common or socially acceptable

Show that others are already engaging in the behaviour |

Note: * These insights are suggested to be effective based on qualitative research and theoretical insights. They have not been empirically evaluated and therefore the evidence is not as strong.

Checklist for behavioural communications

Overview

(TABLE PLACEHOLDER)

Written messaging and content

The ‘words’ in the communication

(TABLE PLACEHOLDER)

Visual design and images

The visual design of, and images in the communication

(TABLE PLACEHOLDER)

Message delivery, including channels of communication

The method and channel(s) of delivery to the audience

(TABLE PLACEHOLDER)

[1] The paragraph and examples are available from The New Hampshire Pollution Prevention Program, des.nh.gov.

[2] The New Hampshire Pollution Prevention Program is available to help with more waste reduction strategies. Please feel free to contact us at (603)271-6460 or email nhppp@des.nh.gov.

[3] WRAP UK. Food waste communications. In: Household Food Waste Collections Guide. Section 6.

[4] AK Research & Consulting. 2023. Food Scraps Collection Qualitative Research: Among Those Not Currently Using the Service. Prepared for the Ministry for the Environment.

[5] Ipsos. 2015. Waste and Recycling: Campaign Concept Testing. Prepared for NSW Environment Protection Authority.

[6] Ministry for the Environment. 2023. Best practice communications for waste minimisation: A guide to support effective behaviour change within households. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

[7] Ministry for the Environment. 2023. Best practice communications for waste minimisation: A guide to support effective behaviour change within households. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment.

[8] WRAP UK. 2021. Household Food Waste Collections Guide. WRAP UK.

[9] NSW Environment Protection Authority. 2021. Scrap Together: FOGO ‘Deep Dive’ Education Project Evaluation Report. Parramatta: NSW Environment Protection Authority.

[10] Metropolitan Waste and Resource Recovery Group. 2019. Food Waste Recycling Social Research Elements of Effective Communications.

[11] Macklin J, Jungbluth L, Raj K. Unpublished. Starting Scraps Co-Design Workshop Summary. Melbourne: BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University.

[12] McNally, B. (2016). Six tips for communicating the challenge of plastic pollution. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

[13] Downes, J., Borg, K., Tull, F., Kaufman, S. (2021). Reducing Contamination of Household Recycling via Educational Flyers. Melbourne: BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University.

[14] Ipsos. 2015. Waste and Recycling: Campaign Concept Testing. Prepared for NSW Environment Protection Authority.

[15] Peat, R. Unpublished. LFHW Around the World. Love Food Hate Waste UK.

[16] Kaufman S, Meis-Harris J, Spanno M, Downes J. 2020. Reducing Contamination of Household Recycling: A rapid evidence and practice review. Melbourne: BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash University.

[17] Recycling Services at Staples | Staples. (n.d.). https://www.staples.com/stores/recycling