Chapter 8a: Communicating Food and Agricultural Industries

“Cutting food waste is a delicious way of saving money, helping to feed the world, and protect the planet.” – Tristram Stuart, English author and environmental campaigner.

Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Describe the role of communication in sustainable agriculture and how it can improve consumer trust and influence consumer behaviors.

- Identify the major sources of greenhouse gas emissions in the food sector and discuss strategies to mitigate these emissions.

- Explain the differences between organic and GMO foods, including their environmental impacts and consumer perceptions.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of different sustainable food practices, such as organic farming and the integration of plant-based alternatives in diets.

- Discuss the importance of ethical food marketing and how it can influence consumer choices and drive demand for sustainable products.

- Recognize the benefits and challenges of using animals for farm labor and how these practices fit into sustainable farming models.

- Utilize a variety of strategies for reducing food waste, including the food recovery hierarchy and the concept of upcycled foods.

- Identify the roles of various stakeholders, including corporations and NGOs, in fostering partnerships to address food insecurity and promote sustainable practices.

Introduction

From agriculture to food marketing, clear and accurate communication about where our food comes from and what is done with it afterwards can help address consumer concerns, enhance marketing efforts, and mitigate excess food waste. This chapter explores strategies for communicating in these sectors, covering key areas such as sustainable agriculture practices, food marketing, and reducing food waste. According to wastedfood.com, forty percent of the edible food that we produce is currently wasted, especially vegetables. Not only do we waste nutrients when we toss out food, but we also waste the energy required to preserve it. This includes the energy required to grow, harvest, process, and transport food. Additionally, food waste accounts for a proportion of our nation’s astounding usage of pesticides, fertilizers, irrigation water, packaging, and landfill space. [1]

Why Food and Agriculture Matter in Environmental Business Communication

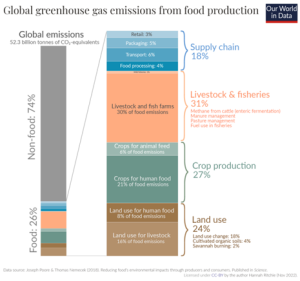

To combat climate change, ‘clean energy’ alternatives usually come to mind first, like renewable energy, energy efficiency improvements, and low-carbon transport. As discussed in the previous two chapters, energy emissions—from electricity, heat, transport, and industry—make up 74% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. [2] The second highest, about 26% of worldwide GHG emissions, come from the production, processing, and distribution of food. We don’t yet have any viable “clean” technological answers for all of the processes involved in growing and transporting the amount of food needed to fulfill a society. When quantifying food GHG emissions, four factors are important: supply chain, livestock and fisheries, crop production, and land use. Categories are indicated in the visual below:

The visual below shows all greenhouse gas emissions, with 26% being food, and 74% make up the rest, titled “non-food”. Of the “food” greenhouse gas emissions, supply chain makes up 18%, livestock and fisheries make up 31%, crop production 27%, and land use 24%.

Reducing food production emissions will be a major task in the next few decades. We need fertilizers to fulfill food demand, yet cattle can’t stop creating methane. Dietary modifications, food waste reduction, agricultural efficiency improvements, and scalable and inexpensive low-carbon food alternatives are needed. [4]

Now that we understand the overall importance of the food sector in sustainability conversations, it’s time to explore the specific environmental costs tied to different food systems, especially how what we eat shapes our planet’s future. After discussing animal labor, we will delve into eating meat compared to plant-based meat, and then strategies for reducing food waste and how to communicate ethically in food industries.

The Role of Animals: Labor, Welfare, and Environmental Impact

Ecological Benefits for Using Animals for Farm Labor

The use of animal labor in sustainable farming offers numerous benefits that align with ecological and economic sustainability. One significant advantage is that animals naturally produce manure, which can be used as organic fertilizer, enhancing soil fertility and reducing the need for synthetic fertilizers. This practice contributes to a closed-loop system, where waste products are recycled back into the ecosystem, promoting soil health and sustainability. [5]

Additionally, animals can graze on grass and other vegetation, effectively managing cover crops and reducing the need for mechanical lawn mowers. This grazing not only maintains the landscape but also provides a source of nutrition for the animals, further integrating them into the farm ecosystem. Moreover, animals can reproduce, providing a self-sustaining labor force that can be expanded over time without significant additional investment. [6]

Unlike machinery, animals do not require technical maintenance, repairs, or fuel, which can be costly and time-consuming. They are less prone to breakdowns and can function in various weather conditions where machinery might fail. Furthermore, animals do not necessitate an HR department to handle grievances or labor disputes, as they do not have the capacity to voice complaints or require personnel management, simplifying farm operations. [7]

Drawbacks of Using Animal Labor

Despite these advantages, there are notable drawbacks to relying on animal labor. Animals typically work at a slower pace compared to modern machinery, which can limit the efficiency and productivity of farming operations. For instance, plowing a field with oxen or horses is significantly more time-consuming than using a tractor, potentially impacting the scale and speed of farm work. [8]

Animals also have physical limitations and can become exhausted, particularly during intensive tasks. Unlike a tractor that can be refueled and continue working, animals require rest, food, and water to recover their energy, which can interrupt and slow down farm activities. This need for rest means that animals might not be able to work continuously for long periods, reducing overall work output compared to mechanical alternatives. [9]

Additionally, managing a labor force of animals involves challenges such as ensuring their health and well-being, known as animal welfare. Animals can suffer from diseases, injuries, and other health issues that can reduce their effectiveness as laborers and incur veterinary costs. Moreover, while animals do not require an HR representative, ethical considerations regarding their treatment and welfare are increasingly important, requiring farmers to adhere to humane practices and potentially limiting some of the perceived labor benefits.

Humanewashing is another term for when businesses claim to be more ethical than they really are with animals. Humanewashing efforts can range from using terms like “happy sheep”, “farm fresh”, “pasture-raised”, or “responsibly raised” on labels or on websites. More implicitly, the imagery on labels or in video advertisements may show joyful animals in open, green, picturesque pastures, when in reality, they are warehoused in dark buildings. [10]

Advocacy groups like Mighty Earth or Rainforest Action Network frequently publish reports on the lack of transparency in “sustainable” sourcing claims by major food companies. Specific examples are often found in investigative journalism or reports from organizations monitoring supply chain practices, particularly those with complex global supply chains (coffee, chocolate, palm oil). [10] Below is a real example of a nonprofit’s “About Us” statement and how it partners with farmers around the world.

Sustainable farming “About Us” statement example. To address all kinds of audiences, one nonprofit explains its mission and values in one paragraph:

“At Tillers International, our dedication goes beyond teaching: it’s about forging meaningful partnerships with small-scale farmers across the globe to enhance food security and community resilience. Our approach is rooted in the sharing of traditional homesteading skills and innovative tools, tailored to empower communities to thrive sustainably. Through dynamic collaboration with local partners in various developing regions, we engage in rigorous research and practical education to co-create farming systems that are not only sustainable but also adaptable to the challenges of climate change, using resources that are readily available within these communities. We invite you to delve deeper into our global mission, explore the inspiring initiatives it has sparked, and discover the various ways you can contribute to this transformative journey. By clicking below, you’ll uncover stories of empowerment, innovation, and the collective effort to build a more food-secure world, one community at a time.”[12]

In conclusion, good communication and openness are essential whether an organization uses animal labor or not. If a company uses animal labor, it must explain why to satisfy concerns from passionate stakeholders who may protest. Highlighting sustainability advantages such natural manure generation, grazing, and fossil fuel savings might assist this approach. If an organization rejects animal labor, it should explain its stance on animal welfare and other environmental actions it takes when farming. This might involve investing in renewable energy, supporting organic farming, or using sophisticated agricultural technology. Organizations may create trust and show ethical and sustainable practices by openly addressing these issues.

While debates about animal labor and meat products raise important questions about sustainability in food production, some companies are taking advantage by replacing meat with plants. Before looking into how businesses communicate about beef, it’s necessary to explain its importance on environmental sustainability.

Beef’s Impact on the Planet

Nearly half of American food’s land usage and greenhouse gas emissions come from beef. [13] Americans consume 10 billion burgers annually. [14] Compared to other animal-based foods, beef production uses the most irrigation water per pound. [15] McDonald’s believes that beef production accounts for 28% of its corporate carbon footprint, equivalent to its energy usage across all res-taurants and headquarters. [16] As businesses and consumers become more aware of these environ-mental impacts, they often seek out food products that claim to be “better” for the planet, such as by implementing “plant-based” meats.

Increase in Plant-Based Meats to Compete with Beef

The environmental costs of beef production—from methane emissions to deforestation and high water usage—have contributed to the rising popularity of plant-based meat alternatives. These innovations aim to reduce our dependence on resource-intensive animal agriculture while still meeting consumer demand.

Former Stanford University School of Medicine biochemistry professor Pat Brown \ founded Impossible consumables in 2011 to replace animal-based consumables with tasty, healthy, and inexpensive plant-based meat and dairy. He released the Impossible Burger in 2016 after five years of investigating why humans seek meat, molecularly understanding animal sources, and recreating its texture, taste, and scents using plant-based components.

Despite its tremendous expansion, Impossible Foods prioritizes environmental and conservation issues. In 2017, the company’s first sustainability study showed that the Impossible Burger consumes 75% less water, 87% fewer greenhouse gasses, and 95% less land than cow-based ground beef. This product has no hormones, antibiotics, cholesterol, or artificial flavors. According to the paper, “widespread adoption of plant-based meats will make it 100% possible to feed the population, provide nourishment and enjoyment, and help preserve the planet for future generations.” [17]

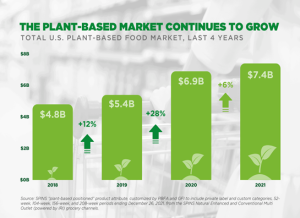

Sodexo’s 75/25 beef-mushroom Natural burger combines nutrition and taste for a satisfying meal. A growing category of blended meals, like The Natural, are plant-forward yet include less meat, resulting in less calories, salt, cholesterol, and carbon footprint that both omnivores and flexitarians may appreciate. Below shows the rise of plant-based market in the US from 2018-2021, rising from 4.8 billion dollars to 7.4 billion:

Using the words “plant-based”, shades of green, and various leaves on packages and websites could be misleading. Some consumers may believe that plant-based meats are healthier than meat itself. Below is a chart comparing the Impossible Burger to an average beef burger nutrition facts. It says a beef burger has 230 calories, where the Impossible Burger has 240. Beef has 22g of protein and the Impossible Burger has 19. The Impossible Burger also has more saturated fat, carbs, and fiber than the average beef burger. The largest difference is the sodium: the beef burger has 64 mg and the Impossible Burger has 370.

Adding plants to beef. Another solution to reducing beef consumption is adding mushrooms to burgers. Burgers account for just one-third of US ground beef consumption. If plants were added to all ground beef dishes—tacos, chili, lasagna, meatballs, pasta sauces, etc.—the environmental advantages may be greater. This could reduce agricultural production-related greenhouse gas emissions by 10.5 million tons of CO2e per year, equal to removing 2.3 million automobiles and their exhaust emissions; reduced irrigation water demand by 83 billion gallons per year, equivalent to 2.6 million Americans’ household water consumption; and reduced global agricultural land need by over 14,000 square miles, greater than Maryland. [20]Reducing meat consumption could lower the demand for beef, leading to fewer greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, the rise of plant-based meat alternatives is encouraging innovation in eco-friendly food production. Beyond production, another major sustainability concern is food waste. Fortunately, businesses have begun to tackle this challenge through upcycling and innovative partnerships across the supply chain.

Food Waste, Upcycling, and Creative Business Solutions

Food Recovery Hierarchy

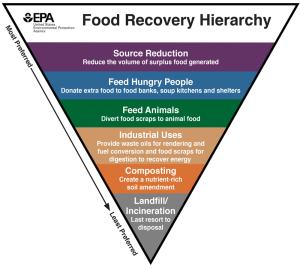

Below is a visual on how food waste can be reduced. It is an inverted pyramid with “source reduction (reduce the volume of surplus food generated)” on the top. Then it has “feed hungry people (donate extra food to food banks, soup kitchens, and shelters” second. Then it has “feed animals (divert food scraps to animal food)” below. Then it has “industrial uses (provide waste oils for rendering and fuel conversion and food scraps for digestion to recover energy).” Then it has “composting (create a nutrient-rich soil amendment)” and finally “landfill/incineration (last resort to disposal)” on the bottom. The top is “most preferred” and points down to “least preferred.”

Upcycled Food to Reduce Waste

Around 28% of agricultural land is used to grow food that is ultimately never eaten. About $1 trillion USD per year is lost on food that is wasted or lost around the world. Eight percent of human-cause greenhouse gas emissions come from food loss and waste, which is why reducing food waste is considered the single greatest solution to climate change according to Project Drawdown. Upcycled ingredients could also be included in animal feed, pet food, cosmetics, home or personal care and more. [22]

¡Yappah! The new Tyson Innovation Lab snack brand inspires customers to rethink snacking with its upcycled food. The first product under the new brand, Protein Crisps, was manufactured with Molson Coors and other partners. The four-flavored crisps use salvaged vegetable and grain materials. [23] An example of its press release is in the next chapter.

Partnerships to Help Address Food Insecurity Around the World

Establishing partnerships between governments, NGOs, and the private sector requires professional and persuasive communication. Partnerships are also effective in addressing food insecurity. Successful case studies can inspire similar initiatives from one organization to another. [24]

Although much of this chapter discusses issues regarding communication about food and agriculture, it is necessary to point out that global warming impacts availability (security) or unavailability (insecurity) around the world. Food insecurity remains a critical global issue in 2022, affecting millions of people. COVID-19, wars, and climatic shocks have increased hunger. According to the 2023 State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World report, 691–783 million people were hungry in 2022, up 122 million from 2019. The research also shows that 2.4 billion people were moderately or severely food insecure and 900 million were severely food insecure. Over 3.1 billion couldn’t afford nutritious food. Malnourished children under five are common. [25]

Consider the recent agreement between The Nature Conservancy, Nestlé Purina, and Cargill to reduce water consumption to irrigate Nebraska row crops that feed cattle to increase beef supply chain sustainability. The Midwest Row Crop Collaborative, a consortium of prominent corporations and conservation groups, started the three-year initiative to accelerate farmer-led water conservation, water quality, and soil health projects in important agricultural states. The project’s irrigation system is designed to cut water usage and be scalable for farmers nationwide.

The first-ever smart weather sensors from Arable Labs will allow farmers to remotely operate and monitor their irrigation equipment from their cellphones. This system optimizes irrigation and saves farmers time and energy. They predict that the scheme will save 2.4 billion gallons of irrigation water over three years, enough for 7,200 people.

International Flavors & Fragrances (IFF), recently named to Barron’s 100 Most Sustainable Companies index, is partnering with Mars Wrigley Confectionery to improve mint farming in India through Shubh Mint, a global project that advances mint plant science and supports mint farmers and their communities. One million smallholder farmers in India produce 80% of the world’s mint, but agricultural productivity decreases are threatening their farms and communities. By sponsoring a community center through READ India, a nonprofit organization that builds community library and resource centers and launches small businesses to empower women and create educational and economic opportunities in rural areas, IFF is helping women gain skills to offset financial pressures caused by mint crop challenges. [26]

Sustainability in agriculture isn’t just about what’s on our plates. Businesses are also responsible for the words they choose when they communicate their attempts to sustain the planet and reduce waste.

Misunderstood Labels: Organic, Natural, Sustainable?

In addition to communicating whether a product is organic or involves animals, effective food marketing can influence consumer choices, drive demand for sustainable products, and foster brand loyalty. However, it requires a balance between promoting products and ensuring ethical and accurate representations.

Regenerative agriculture

The term regenerative in food production refers to agricultural practices that restore and improve the health of ecosystems, especially soil, instead of sustaining current conditions. Regenerative agriculture often includes techniques such as cover cropping, rotational grazing, reduced tillage, and composting to increase biodiversity, enrich soil, and enhance carbon sequestration. Many businesses now use the word regenerative to position their products as climate-positive or more environmentally beneficial than conventional or even organic options. However, because the term is not strictly regulated, its use in marketing can vary widely, leading to concerns about potential greenwashing if not backed by transparent practices or certifications. [27] Below is an image that advertises a type of beef, saying “Know your farmer. Know your beef. Our fresh, regeneratively raised beef is ready for purchase. Order now.”

Organic vs. GMO Foods: Understanding the Differences

The debate between organic and genetically modified organisms (also referred to as GMOs or genetically modified foods) is a significant topic in food communication. Organic foods are produced without synthetic pesticides, fertilizers, or GMOs, while GMO foods have had their DNA altered for specific traits. [29] While organic farming is often perceived as more environmentally friendly, GMOs can offer higher yields and reduced pesticide use. [30] Consumers need clear and factual information to make informed choices about their foods, so companies should use recognized certifications and labels like USDA Organic, Fair Trade, or Rainforest Alliance to communicate adherence to sustainable practices. [31]

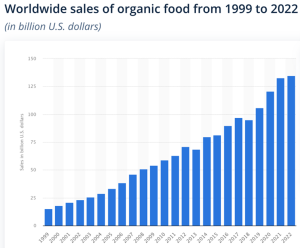

As shown in the graph below, the global sales of organic food have increased between 2000 and 2022. In 2022, sales of organic food amounted to about 134.76 billion U.S. dollars, up from nearly 18 billion dollars in 2000.

Organic farming has a smaller carbon impact since fossil fuel-based fertilizers and most synthetic pesticides are prohibited. Energy-intensive agriculture chemicals are made instead. Studies demonstrate that eliminating synthetic nitrogen fertilizers alone, as in organic systems, might reduce worldwide agriculture greenhouse gas emissions by 20%. [33] A forty-year Rodale Institute research found that organic farms use 45% less energy than conventional farms while maintaining or surpassing yields following a 5-year changeover period. [34] Fumigant insecticides, applied on strawberries and sprayed into soil, release N2O, the strongest greenhouse gas. Research shows that chloropicrin, a fumigant insecticide, may increase N2O emissions by 700-800%. Metam sodium and dazomet also enhance N2O production. [35] Organic farming also improves soil carbon sequestration and promotes resiliency by boosting the soil’s ability to retain water and the natural nutrients found in healthy soils. [36]Below are common certifications related to food and ethical treatment of animals: You can familiarize yourself with these real certificates to support other businesses that have them or you can aim for your company to earn one as well. In addition to the certificates, word choices in food marketing can boost a company’s reputation—or threaten it.

You can familiarize yourself with these real certificates to support other businesses that have them or you can aim for your company to earn one as well. In addition to the certificates, word choices in food marketing can boost a company’s reputation—or threaten it.

Localwashing is similar to greenwashing but it is when companies claim food is more from more local and eco-friendly origins than in reality. It supports the idea of “feel-good phrases with no verifiable impact.” Hellmann’s mayonnaise labels included a claim that the company was “committed to sustainable farming.” However, there was little transparency about what that meant, no third-party certification or clear criteria, making it a vague, feel-good phrase with no verifiable impact. [37]

Using “Natural” Unnaturally. Several major food brands have come under scrutiny for using the term “natural” in misleading ways. Tyson Foods marketed its chicken products as “100% natural,” despite using antibiotics, processing chemicals, and unnatural feed additives. In 2008, Tyson was sued and eventually agreed to remove the label from their packaging following a court ruling. [38] Lay’s Potato Chips changed its packaging to earth-tone colors and added “All Natural” to the label to appeal to environmental and health-conscious consumers. However, the ingredients and processing methods remained the same, leading critics to argue that the change was superficial and deceptive. Kashi, a brand known for health foods, promoted its cereal as “natural” while using genetically modified soy and synthetic ingredients. This led to consumer backlash and a class-action lawsuit, pushing the brand to reconsider its labeling practices. Because the terms “natural”, “100% natural”, or “all natural” were not formally defined by neither the FDA nor USDA, food marketers can use the terms as they deem fit. [39] Below is an image of Cheetos and above the brand name it says “Natural.” The last section will explain strategies for more effective communication about food.

Strategies for Clear and Ethical Communication about Food

More effective communication strategies for food marketing include the following:

- Advertise Honestly. Avoid misleading claims about the health benefits or origins of food products. Accurate labeling is essential to maintain consumer trust. [41]

- Engage through Social Media. Utilize social media platforms to engage with consumers, share recipes, provide information about sourcing, and respond to inquiries. This interaction can build a loyal customer base. [42]

- Implement Educational Campaigns. Educate consumers about the benefits of sustainable and healthy eating. This can include information on nutritional value, environmental impact, and ethical sourcing. [43]

- Address Food Waste. Food waste has substantial environmental, economic, and social impacts (refer to a previous chapter for more on waste or the hierarchy above). Communicating strategies to reduce food waste can help raise awareness and encourage more sustainable behaviors. For example, the product label or container could include instructions on how to store the food inside it and for how long.

- Have Clear Expiration Labels. Food-related business owners can improve the clarity of expiration labels to reduce confusion and prevent premature disposal of food items. Labels such as “expires on”, “best by”, and “use by” should be clearly differentiated. [44]

- Collaborate with Stakeholders. Farmers and food-related businesses can work with retailers, restaurants, and consumers to develop initiatives aimed at reducing waste, such as donating surplus food or creating secondary products from unsold goods. [45]

Conclusion

Effective communication in the food and agricultural industries is essential for promoting sustainability, building consumer trust, and reducing food waste. By employing transparent practices, ethical marketing, and collaborative efforts to reduce waste, these industries can contribute to a more sustainable future.

[1] Wasted Food. (n.d.). http://www.wastedfood.com/about/

[2] IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151.

[3] Poore, J., & Nemecek, T. (2018). Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science, 360(6392), 987-992.

[4] Ritchie, H., & Roser, M. (2024, March 18). Food production is responsible for one-quarter of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/food-ghg-emissions

[5] Pimentel, D., Hepperly, P., Hanson, J., Douds, D., & Seidel, R. (2005). Environmental, energetic, and economic comparisons of organic and conventional farming systems. Bioscience, 55(7), 573-582.

[6] Martínez-Fernández, A., Ranilla, M. J., Tejido, M. L., & Carro, M. D. (2020). Use of grazing animals in sustainable agricultural systems. Journal of Animal Science, 98(1), skz394.

[7] McGuire, J., Morton, L. W., Arbuckle, J. G., & Cast, A. D. (2022). The role of animals in sustainable agriculture. Sustainability Science, 17(4), 1113-1128.

[8] Schultz, S., Moulton, C. E., & Hart, L. A. (2017). Evaluating animal labor in agriculture. Agricultural Systems, 153, 135-142.

[9] Fraser, D. (2014). The role of animal welfare in sustainable agriculture. Animal Frontiers, 4(3), 25-30.

[10] Changing Markets Foundation. (n.d.). Feeding Us Greenwash: An analysis of misleading claims in the food sector. From https://changingmarkets.org/report/feeding-us-greenwash-an-analysis-of-misleading-claims-in-the-food-sector/

[11] Roach, G. (2024). ESG Scrutiny: Mighty Earth campaign group shares approach to weeding out greenwashing. Governance Intelligence. From https://www.governance-intelligence.com/esg/esg-scrutiny-mighty-earth-campaign-group-shares-approach-weeding-out-greenwashing#:~:text=ESG%20scrutiny%3A%20Mighty%20Earth%20campaign,weeding%20out%20greenwashing%20%7C%20Governance%20Intelligence

[12] Making History Present (n.d.). Tillers International. From https://tillersinternational.org/about/

[13] Searchinger, T., Waite, R., & Hanson, C. (2022, March 7). How to reduce food’s greenhouse gas emissions. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/how-reduce-food-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[14] Searchinger, T. D. (2018, February 22). The global viability of reducing beef consumption in the U.S. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/insights/global-viability-reducing-beef-consumption-us

[15] The Beef Cattle Institute. (2020, November 16). Cattle Chat: How much water is needed to produce a pound of beef? Kansas State University. https://www.k-state.edu/beef/cattlechat/news/2020/11/16-water-pound-beef.html

[16] Trellis Group. (2014, January 7). McDonald’s carbon footprint of beef is equal to its energy usage across all restaurants. https://www.trellisgroup.com/2014/01/mcdonalds-carbon-footprint-of-beef-is-equal-to-its-energy-usage-across-all-restaurants/

[17] Malochleb, M. (2018). Sustainability: How Food Companies are Turning Over a New Leaf. Food Technology Magazine. https://www.ift.org/news-and-publications/food-technology-magazine/issues/2018/august/features/sustainability-at-food-companies

[18] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/09/food-plants-sustainable-eating-climate-change/

[19] Promise-Problem in Impossible Burger. (n.d.). Blue Bird Provisions. https://bluebirdprovisions.co/blogs/news/promise-problem-impossible-burger

[20] Waite, R. & Vennard, D. (2018). Mushroom-beef burgers from Sodexo, Sonic are cutting calories and emissions. GreenBiz. https://www.greenbiz.com/article/mushroom-beef-burgers-sodexo-sonic-are-cutting-calories-and-emissions

[21] Prevent Wasted Food Through Source Reduction | US EPA. (2023, October 19). US EPA. https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/prevent-wasted-food-through-source-reduction

[22] About Upcycled Food. (2025). Upcycled Food Association. From https://www.upcycledfood.org/upcycled-food#:~:text=1.,food%20that%20is%20never%20eaten.

[23] Kurman, C., & Thompson, J. (2018). Tyson Innovation Lab Launches ¡Yappah! Brand to Help Fight Food Waste Through a Unique Chef-Driven Lens. Tyson Foods. From https://www.tysonfoods.com/news/news-releases/2018/5/tyson-innovation-lab-launches-yappah-brand-help-fight-food-waste-through

[24] Smith, L., & Thompson, M. (2020). Collaborative efforts to combat food insecurity: A global perspective. International Journal of Food Policy, 29(4), 456-470.

[25] Food | United Nations. (n.d.). United Nations. https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/food#:~:text=Food%20security%20and%20nutrition%20situation%20remains%20dire%20in%202022&text=According%20to%20the%202023%20edition,million%20people%20compared%20to%202019.

[26] Malochleb, M. (2021). How Food Companies Meet Demands for Sustainability. Food Processing. https://www.foodprocessing.com/food-safety/environmental/article/11293306/how-food-companies-meet-demands-for-sustainability

[27] Gosnell, H., Gill, N., & Voyer, M. (2019). Transformational adaptation on the farm: Processes of change and persistence in transitions to ‘climate-smart’ regenerative agriculture. Global Environmental Change, 59, 101965. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2019.101965

[28] Know your beef. (2025). Favour Farm. From https://www.instagram.com/reel/DHYEdoDqxmS/?locale=zh_CN

[29] USDA. (2022). Organic 101: What the USDA organic label means. United States Department of Agriculture.

[30] National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Genetically Engineered Crops: Experiences and Prospects. The National Academies Press.

[31] Johnson, T., & Patel, R. (2021). The role of certifications in promoting sustainable agriculture. Environmental Economics, 10(4), 242-256.

[32] Shahbandeh, M. (2024). Worldwide sales of organic foods 1999-2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/273090/worldwide-sales-of-organic-foods-since-1999/

[33] Başay, S. (2022). From climate change adaptation strategies; organic farming. Reviews in Agriculture, Forestry and Aquaculture.

[34] Merrigan, K., Giraud, E. G., Scialabba, N. E. H., & Brook, L. (2022). Grow Organic: The Climate, Health, and Economic Case for Expanding Organic Agriculture. Reviews in Agriculture, Forestry and Aquaculture.

[35] Demirtas, M. (2021). Evaluation of energy use and carbon dioxide emissions from the consumption of fossil fuels and agricultural chemicals for paste tomato cultivation in the Bursa region. Environmental Science and Pollution Research.

[36] Mathur, S., Waswani, H., Singh, D., & Ranjan, R. (2022). Alternative fuels for agriculture sustainability: carbon footprint and economic feasibility. AgriEngineering.

[37] Hiskes, J. (2009, September 5). ‘Localwashing’ in pictures — bogus marketing at its finest. Grist.org. Retrieved July 16, 2025, from https://grist.org/article/2009-09-04-in-pictures-a-tour-of-corporate-localwashing/

[38] Shanker, D. (2012). Is the natural label 100% misleading? Grist. From https://grist.org/food/is-the-natural-label-100-percent-misleading/#:~:text=The%20FDA%20says%20on%20its,it%20since%20the%20late%201970s.

[39] Dunckel, M., Schweihofer, J., & Decker, A. (2020). Natural and Organic Label Claims. Michigan State University Extension Agriculture. From https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/natural-and-organic-label-claims

[40] Bobo, J. (2020). Viewpoint: 70% of consumers say ‘natural’ food is healthier, but there’s no science behind the marketing hype. Genetic Literacy Project. From https://geneticliteracyproject.org/2020/06/04/viewpoint-70-of-consumers-say-natural-food-is-healthier-but-theres-no-science-behind-the-marketing-hype/

[41] Brown, D. (2019). Ethical advertising in the food industry: Challenges and solutions. Journal of Business Ethics, 159(2), 385-402.

[42] Kim, H., & Park, J. (2020). Social media strategies for engaging consumers in sustainable food practices. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 51, 64-75.

[43] Lopez, S., & Murray, P. (2018). Educational campaigns for promoting healthy and sustainable eating habits. Health Communication, 33(9), 1153-1161.

[44] Nelson, A. (2020). The impact of clear expiration labeling on food waste reduction. Journal of Consumer Policy, 43(3), 573-590.

[45] Clark, E. (2019). Reducing food waste through stakeholder collaboration. Sustainability in Agriculture, 11(3), 569.