Chapter 1b: Storytelling in Business Communication

Storytelling in Sustainable Businesses

The first chapter laid out important terms for business sustainability and business communication. The next (odd) chapters will explore challenges when businesses communicate sustainability. The even chapters will provide practical examples of businesses/nonprofits communicating sustainability.

By the end of this chapter, students will be able to:

- Articulate how storytelling can make sustainability messages resonate more personally with audiences.

- Analyze effective stories that can strengthen relationships, strategy, and culture within organizations.

- Evaluate when and how to use storytelling to express scientific and numerical information.

- Create compelling narratives that illustrate the pursuit of a sustainable future.

In Poetics—Aristotle proposed that stories were a source of self-understanding. Aristotle maintained that theater was necessary to arouse people’s emotions and aided self-understanding. [1]

Narratives can help messages resonate more personally with audiences. Storytelling can strengthen relationships, strategy, and culture in organizations as well. Executives unite teams, inspire them, and express a vision with stories that are authentic, humorous, creative, and fascinating. Stories attract great personnel and more customers. It can be as simple as explaining how you got started or became interested in pursuing your business.

Green and Brock (2000) argue that stories:

- foster involvement with storyline, characters

- increase message acceptance while decreasing counter-arguing (memory tends to be high so educational content can be conveyed)

- can be as absorbing if fictional as non-fiction stories [2]

Sustainable Business Storytelling

The notion of creating a story envisioning a “smarter planet” with sustainability at its core inspired IBM’s comeback when competing against Apple in 1984. IBM earns money by helping clients predict future risks and possibilities. Their 2015 strategy includes four growth initiatives, including Smarter Planet. Business income from Smarter Planet programs increased 50% between 2010 and 2011.

Stories are crucial for communicating complicated concepts, especially about environmental sustainability, since global readers may not be familiar with the science behind the organization. Stories require little cognitive work from the recipient and can be entertaining, which is a major benefit to paying attention to them. Stories simplify facts and data so that they are easier to understand than complex studies or specialized publications. This simplified technique follows what is known as peripheral or heuristic information processing, which uses visual imagery, humor, and reputable sources to interest viewers or readers. [3] Stories captivate attention and help listeners comprehend the subject matter intuitively, allowing them to connect with the topic more personally.

Stories may also promote healthy social standards and change society. Effective storytelling shows that climate-friendly practices are useful and appreciated in communities. Stories that include eco-conscious people or situations inspire viewers to adopt similar habits, promoting sustainability. Stories create urgency and relevance by exposing consequences on emotional or physical destinations like national parks or treasured sites. Adding relevant characters, such as celebrities or people the audience can relate to, boosts the story’s emotional effect. This individualized approach emphasizes climate issues’ urgency and builds viewer/reader empathy and unity. This strategy follows the maxim “show rather than tell,” stressing the significance of storytelling above didactic or prescriptive tactics. [4]

By immersing people in fascinating stories, storytelling stimulates active engagement. Stories engage audiences, spark interest, and make them stakeholders in the story via immersive experiences, interactive platforms, or serialized material. Stories may successfully communicate complicated themes like climate change by blending low cognitive effort, heuristic information processing, promotion of good social norms, customized threats, and active engagement.

Effective Storytelling Elements

Dr. Moriarty, professor of business administration at the University of Darden, gives the following tips on creating engaging stories.[5]

- Open with a hook to capture the audience’s attention.

- Set a dramatic atmosphere to attract your audience’s attention right away.

- Clearly state your goal in telling the story to a specific audience.

- Providing detailed descriptions of the protagonist’s shift may help your audience identify with your tale.

- Focus the story on how something transformed (you, your service, the organization, the product, etc.).

- Consider starting in chronological order. Start with the date, year, era, etc. and remember the story should contain “who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” “why,” “how,” etc.

- Structure the story like a journey. TED founder Chris Anderson advises structuring your story as a journey and focusing on its beginning and finish. Multiple plot twists may add tension to your story using this structure. A basic trip framework may also help storytellers stay on track.

- Create a “door” for the audience to enter the story. In addition to establishing common ground between writer/speaker and the audience, questions can evoke memory, stimulate imagination, and fuel an emotion. Examples include:

- “Have you ever felt completely alone?”

- “What would it be like to live in a world where no one goes hungry?”

- “How does it feel when someone cuts in front of you in line?”

- Close with a “bang”. Before you end the story, what should your audience experience last? Which final thing do you want to say and how? Conclusions should be strong and focused on the future. Options include ending with a question, a prediction, some advice, a quote, or a call to action from the audience.

- Get feedback. Professional or peer feedback will help you decide if your account provides too much detail or too little. Did your main message come through to your listener/reader? Which part of your story had the most significant cognitive or emotional impact? You may learn that rearranging or removing story elements will improve understanding or enhance the emotional impact.

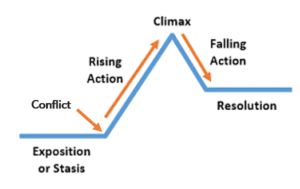

The following is a visual of a typical story being told:

It starts with a horizontal line starting with “exposition or stasis.” Then at the end of the horizontal line it says “conflict.” The line increases with the label “rising action.” Then this line bends at the top with the label “climax.” The line starts to go down with the label “falling action.” Then the line goes horizontally to the right with the label “resolution.”

A complete, professional story is made up of the following parts:

- An introductory section that hooks the reader’s attention

- A moment when the main problem is introduced

- An exploration of the problem

- A final solution

- A conclusion that ties everything together

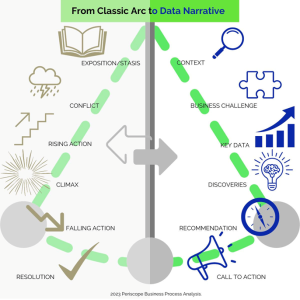

Stories are more than their parts. By analyzing the audience, we can include the right words to grab the audience’s attention, tell the story in an order they can follow, and include info that they can relate to personally. Keep in mind the overall message and the timing of when the story was told as well. Below, one last visual is a side-by-side comparison of the above story telling arc with a data narrative arc:

Instead of “exposition status,” this arc has “context.” Then it points to “business challenge” which points to “key data.” This points to “discoveries,” which points to “recommendation,” then the line goes down to “call to action.”

[1] Green, M. C. & Brock, T. C. (2000). The role of transportation in the persuasiveness of public narratives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(5), 701-721. http://www.communicationcache.com/uploads/1/0/8/8/10887248/the_role_of_transportation_in_the_persuasiveness_of_public_narratives.pdf

[2] Aristotle, ca. 335 B.C.E./2013; Plato, ca. 375 B.C.E./2000; Stern, 2014

[3] Chaiken, S., & Ledgerwood, A. (2011). A theory of heuristic and systematic information processing. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 1.

[4] Sparkman, G., Howe, L., & Walton, G. (2020). How social norms are often a barrier to addressing climate change but can be part of the solution. Behavioural Public Policy, 5(4), 1-28.

[5] Moriarty, B. (2022). Storytelling in Business: How to Create Engaging Stories. Darden Ideas to Action. https://ideas.darden.virginia.edu/storytelling-in-business-engaging-stories