Chapter 3a: Reporting ESG & CSR

“In the early part of this century we must now achieve a new revolution in green consumption… The green movement must become a mass movement in green consumption.”

-Former chief of Tesco Sir Terry Leahy

Objectives:

After reading this chapter, students should be able to

- Identify the different types of sustainability reports businesses create.

- Assess the reasons why some businesses report their environmental impact while others do not.

- Compare sustainability reporting requirements.

- Describe the benefits of CSR for companies, including economic advantages, brand recognition, and employee retention.

- Explain the three pillars of corporate sustainability (environment, social, and governance) and their significance in ESG criteria.

- Identify the key components of a comprehensive sustainability or ESG report.

- Align sustainability reporting with a company’s size, sector, and goals.

Introduction

After reading this chapter, be prepared to discuss the following questions:

- What kinds of reports do businesses create to communicate its impact on the environment?

- Why do some businesses report their impact and some do not?

- Does it solve global warming issues if a government requires businesses to report sustainability?

According to research published in the Journal of Consumer Psychology, consumers are more likely to be favorable to a firm that has taken steps to help its customers. Engaging in corporate social responsibility (CSR) increases the likelihood of a firm receiving positive brand reputation. Moreover, employees are more inclined to remain loyal to a firm they have faith in. [1] Companies that engage in CSR are more likely to receive favorable brand recognition. Additionally, workers are more likely to stay with a company they share values with and trust. This leads to a decrease in staff turnover, discontented employees, and the overall expenses associated with hiring a new employee.

The Boston Consulting Group found that companies considered leaders in environmental, social, or governance matters had an 11% higher valuation premium than their rivals. [2]

Overall, Corporate Social Responsibility strategies enable organizations to proactively manage risk by avoiding involvement in problematic circumstances. This encompasses the prevention of detrimental behaviors such as employee group discrimination, negligence towards natural resources, unethical use of corporate cash, and engagement in actions that result in lawsuits and litigation.

Environmental Social Governance (ESG)

ESG, which stands for environmental, social, and governance, refers to how companies score on responsibility metrics and standards for possible investments. Environmental standards evaluate an organization’s efforts to protect the environment. Social criteria assess the organization’s ability to effectively manage its connections with workers, suppliers, consumers, and communities. Governance include the assessment of a company’s leadership, executive compensation, audits, internal controls, and shareholder rights. [3]

McKinsey Research indicates that implementing an ESG strategy has the potential to increase operational profitability by up to 60%. As a matter of fact, 71% of CEOs admit that their organization’s ESG policies align with the principles and beliefs of their consumers. According to Deloitte, assets that are required to meet ESG criteria might account for 50% of all investments handled by professionals by 2024. This would amount to a total of $35 trillion. [4]

Each category within ESG overlaps with the 3 pillars of corporate sustainability:

- Environment: Potential risks that the firm may encounter in relation to waste management, pollution control, corporate climate policy, energy consumption, conservation of natural resources, and the ethical treatment of animals.

- Social: The organization’s interactions with stakeholders, charitable contributions, and working conditions provided to workers.

- Governance: The effectiveness of a company’s management and the extent to which the executive management and board of directors prioritize the interests of the company’s stakeholders are evaluated. This evaluation includes sharing transparent and comprehensive financial reports, as well as adhering to ethical and legal management practices.

Criteria Used for ESG and Sustainability Reporting

Sustainability reporting, also known as Trible Bottom Line (TBL) reporting, has been increasingly popular with businesses and nonprofits over the past decade worldwide. Over 80% of the top 250 global corporations reported on their social or environmental effects in 2008, up from more than half in 2005. [5] In 2022, 96% of the largest 500 companies by market cap published a sustainability report in 2022. Many more companies have adopted sustainability reporting since. [6]

Because of this, it’s critical to understand the fundamental reporting standards and criteria, as well as how to construct a sustainability or ESG report, in order to provide data that is reliable, consistent, and comparable.

There are also country, state, and stock-exchange specific sustainability reporting standards like Australia’s upcoming climate disclosure law, sustainability reporting requirements from the Singapore, Hong Kong, and Dubai stock exchanges, California’s Climate Corporate Data Accountability Act (SB 253), and the SEC’s proposed rule on climate disclosure. [7]

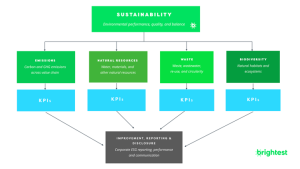

Below is a visual showing “sustainability” in a rectangle. It points to four other rectangles, “emissions, natural resources, waste, and biodiversity.” Each rectangle has a short description. The emissions rectangle says “carbon and GHG (greenhouse gas) across value chain.” Natural resources was described as “water, materials, and other natural resources.” Waste is described as “waste, wastewater, re-use, and circularity.” Biodiversity is described as “natural inhabitants and ecosystems.” All of these rectangles point to their own smaller rectangles called “KPIs”. All the KPI rectangles point to a rectangle that says “improvement, reporting, and disclosure,” described as “corporate ESG reporting, performance, and communication.

Mixed Signals and Credibility in Sustainability Assurance

Floyd and Cardon (2024) define mixed signals in business communication as when someone performs an action but says something different. An example is when a company claims they care about the environment but their reports do not show significant changes made in the past year. Mixed signals can cause confusion, create frustration, waste time, and erode working relationships between organizations and stakeholders. [9]

In practice, organizations and those reporting their sustainability practices (assurers) jointly determine the intensity and scope of the performed assurance process (how to report one’s environmental sustainability efforts). This collaboration influences the likelihood of discovering problematic issues in a sustainability report.

Purposefully imprecise communication or an obscured scope of assurance may violate ethical assurance norms and undermine sustainability reporting credibility. Baier et al. (2021) use the term reference explicitness to describe whether firms choose to indicate the assured topics in a more or less explicit manner, such as visually throughout the sustainability report or verbally. This is important because readers rely on sustainability assurance when evaluating the information in sustainability reports. [10]

Sustainability assurance improves trust by ensuring information is full and transparent. Sustainability assurance may be symbolic if it is seen as solely providing positive information about the company. If so, its main purpose is to deceive sustainability report readers while minimizing effort and expense. If sustainability reports express an organization’s efforts more explicitly and transparently, readers are more inclined to trust the organization. [11] Therefore, sustainability assurance can also be interpreted as an impression management process. [12]

Increasing Importance of Radical Transparency

Chip Hazard wrote a blog post on the importance of monthly investor updates and articulated the “Triple-A rubric” of alignment, accountability, and access. Outside accountability, such as sending out detailed monthly updates, can be a positive forcing function. By being more transparent and accountable, employees and investors feel fully aligned and in a position to be supportive— whether for sales leads, referrals to talent, strategic advice, or partnership opportunities. [13]

Ray Dalio of Bridgewater famously coined the phrase “radical transparency” as a philosophy to describe his operating model at the firm where a direct and honest culture is practiced in all communications. His book, Principles, expands on radical transparency and this overall business and life philosophy. [14]

Greenwashing

Some products might seem to have characteristics of a green product but actually may not have them. These products are said to have “environmental makeup” or are characterized as a greenwashing product.

In the 1980s, greenwashing—making offensive or exaggerated claims of sustainability to obtain market share—became popular. Greenwashing is not new, but its usage is rising due to the growing demand for green and organic goods and the regulatory authorities’ delay in defining norms and rules to manage it. This, combined with ineffective regulation, promotes consumer cynicism about green goods and distrust of environmental solutions in manufacturing, distribution, and marketing. [15]

Thus, greenwashing is positively associated to customer confusion on brand marketing and perceived risks (PRs) in purchasing green items since claims of being “green” can cause frustration when making incorrect purchase choices. In sum, greenwashing hurts the firm because people lose trust in the brand or product. [16]

Triple Bottom Line Increasing in Importance

By prioritizing equitable solutions, policymakers and advocates can ensure that the benefits of sustainable practices are accessible to all, regardless of socio-economic status or geographical location. Therefore, addressing climate issues is intrinsically linked to broader social justice initiatives. One country’s impact on the environment does not only affect that country after all. Economists coined the term triple bottom line (TBL) where companies ought to commit to focusing as much on social and environmental concerns as they do on profits. TBL theory posits that instead of one bottom line, there should be three: profit, people, and the planet. A successful company can be managed in a way that not only makes money but which also improves people’s lives and the well-being of the planet. [17]

The image below shows three circles in green: the first is labeled people, the second profit, the third planet. The three images overlap each other.

Although 90% of executives believe sustainability is important in business, 60% have sustainability strategies due to:

- weak commitment from the board,

- little accountability,

- sustainability teams without authority to implement initiatives,

- and talent gaps. [18]

The benefits of this go beyond environmental and social security. That is, more and more studies indicate business sustainability delivers greater prosperity, and designs organizations to last. Customers also have the power to vote with each dollar spent, and their votes are driving more and more businesses to be truly socially responsible. In fact, 66% of consumers are willing to pay more for a product if the company supports a social or environmental cause. [19]

Conscious Leaders, Businesses, and Capitalism

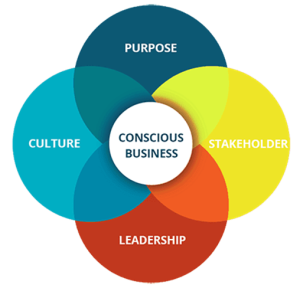

A conscious leader is someone who actually walks the talk, who has determined values and actually lives by them as someone who is conscious and aware of their actions on a daily basis, and who has the ability to respond thoughtfully rather than react. A conscious business is led by someone who embodies and executes the mission for the company in a sustainable manner, with transparency. In the business world, leadership has to be empathetic, possess emotional mastery, and have unflinching integrity in the face of opposition. Leadership development and a willingness to learn at the C-Suite level is a crucial element for a conscious business to thrive. [20]

Supporting conscious businesses has a ripple effect of benefits. In a 2019 CSR Survey conducted by Aflac, 77% of consumers felt motivated to make purchasing decisions from companies committed to making the world a better place, 80% of young Americans are willing to pay more for sustainable products, and 73% of investors viewed these efforts as contributors to return on investment, and, in turn, often look favorably on companies with conscious social and environmental impact. [22] Meanwhile 70% of millennial consumers will stop supporting businesses that don’t align with their personal beliefs. As millennials and Gen Z gain more purchasing power, it is increasingly more important for businesses to adapt to these evolving standards. [23]

Conscious capitalism is the basic belief that acknowledges the evolution of capitalism and the potential for business to elevate humanity through well-executed practices. Instead of redefining what capitalism is and substantially changing it, conscious capitalism builds on what is successful about capitalism and simply incorporates elements like higher purpose, stakeholder orientation, conscious leadership, and conscious culture—all practices that benefit human beings and the planet we live on. [24]

Rebecca Henderson notes in the online course Sustainable Business Strategy: “You can’t use business to do good in the world if you’re not doing well financially. Doing well and doing good are intertwined, and successful business strategies include both.”

Mere sustainability efforts, while commendable, fall short unless effectively communicated and integrated into broader societal frameworks. In this context, communication surpasses mere distribution of information; it requires strategic planning, an understanding of diverse audiences, the potential implications of lawsuits, and careful proofreading. This proactive approach ensures that sustainability initiatives resonate with stakeholders, fostering a collective commitment to environmental stewardship.

Primary and Secondary Damage to Reputation

It might seem straightforward to simply communicate honestly and maintain transparency, but it’s important to think about the broader repercussions when upsetting stakeholders. The extensive and widespread secondary damages may have enduring consequences for a business’s image, consumer trust, and overall prosperity. Below are examples of reputational damage and two stages: primary or episodic and secondary.

[25]

We must be cognizant in our messages, frames, and arguments that some terms may work to trivialize sustainability and our need to reduce impact and risk (note: two very non-passive words).

When it comes to sustainability’s role in reducing regulatory and reputational risk, consider that sustainability works to reduce the exposure of the organization subject to risk. An organization can’t be fined by the EPA or state regulators for hazardous waste it doesn’t have; it can’t be devastated by a public campaign against environmental abuses in which it does not partake. Each movement the organization makes toward sustainability could be seen as a movement from legal, regulatory, and reputational risk. We must be clear that sustainability not only represents a very tangible opportunity for innovation and growth, but that it is part of a core business imperative to reduce risk to the organization.

Sustainability Reporting Standard Examples

[26]

Common Certifications Proving Sustainability

A company may demonstrate its dedication to environmental sustainability with a variety of certifications, which can provide it the required legitimacy and recognition. These certifications are granted based on rigorous standards that evaluate a company’s environmental practices and influence. It is essential for organizations to have a concrete method to assess and convey their sustainability endeavors. By acquiring knowledge about several environmental certifications, readers should be able to analyze one in depth and articulate its importance, standards, and advantages, thereby showcasing a company’s commitment to sustainable operations.

A Summary of Different Certifications

[27]

Why so Many Sustainability Reporting Standards and why do they Differ so Much?

Sustainability reporting operates differently from standard financial accounting in terms of openness, consistency, and interoperability. In 2024, there were over 600 distinct sustainability reporting standards, frameworks, guidelines, and industry efforts worldwide. Consequently, engaging in sustainability reporting may be a complicated, research-intensive, and repetitious undertaking. As a result, most firms adhere to their government’s sustainability reporting regulations. Additionally, businesses and nonprofits may choose to voluntarily adopt certain reporting standards and choose the manner in which they disclose their sustainability achievements. An increasing number of firms, such as Amazon, Walmart, Nike, Disney, and Target, conduct surveys of their vendors and suppliers to gather information about the sustainability practices of their businesses. Although the majority of these surveys are now optional, sustainability reporting criteria are increasingly being enforced by law in some parts of the European Union.

It is critical to use sustainability standards that are consistent with your sustainability and ESG materiality; offer clear key performance indicators (KPIs) and measurement guidance; are widely adopted, suitable for the size, sector, and objectives of your business; and effectively contribute to shaping your sustainability priorities, actions, investments, and decision-making.

Growing Importance of Sustainability Reporting

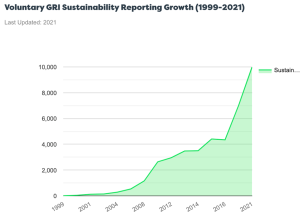

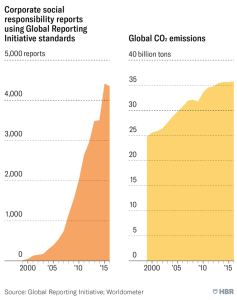

The chart below shows voluntary GRI sustainability reporting growth from 1999-2021. It increased significantly in 2008, then continued to rise steadily, then starkly in 2021.

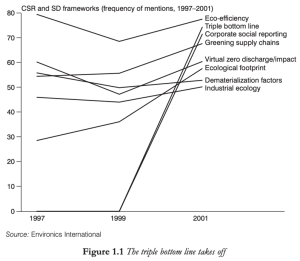

Since 1999, as shown in the chart below, the mention of specific words such as “eco-efficiency” and “triple bottom line” have increased in mentions on CSR reports.

The benefits of sustainability reporting for investors

Sustainability reporting gives investors a means to assess the environmental and social impacts, opportunities, and risks of a company and its operations. This information is critical for informed decision-making, and can help stakeholders understand the potential risks and benefits associated with investing in or doing business with a company. For investors, sustainability reporting provides valuable information that can be used to assess the long-term financial performance and ESG risk of a company. Companies that genuinely prioritize sustainability are statistically better-positioned to manage risks, reduce energy and resource-related costs, limit many types of value chain risk, and create more stable, long-term shareholder value.

The benefits of sustainability reporting for society

While sustainability reporting for the sake of reporting doesn’t necessarily help companies decarbonize or become more sustainable, it does help establish awareness and baselines about a company’s current sustainability performance that often serves as a catalyst for future investment. By providing information on a company’s environmental performance over time, sustainability reporting encourages companies to adopt sustainability targets and circular business practices, which ultimately benefits the environment and society as a whole. [30]

However, as shown in the chart below, global CO2 emissions are still increasing, despite the UN’s, multiple countries’ governments’, and businesses’ attempts to communicate their sustainability goals.

Therefore, discussing sustainability alone is not sufficient to make worldwide changes. More action needs to be done, especially by businesses, since they are organizations mass producing goods with processes that damage our environment. Nonetheless, if and how an organization reports its sustainability demonstrates its values towards shareholders and other stakeholders.

Shareholder versus Stakeholder Theory in ESG Reporting

Since not all products that we demand are necessarily beneficial to our environment (e.g., gasoline or oil), certain industries must report their sustainability efforts given two opposing types of audiences: shareholders (also known as “stockholders’) and stakeholders (everyone else, including but not limited to customers, employees, and the public at large).

These two philosophies of corporate social responsibility describe what a firm should and should not do. Corporate leaders and managers are expected to base their judgments on the morally correct theory, therefore, these models may be seen as normative frameworks for business ethics. Unfortunately the two ideas strongly contradict one other in terms of their perspectives on what is considered morally correct.

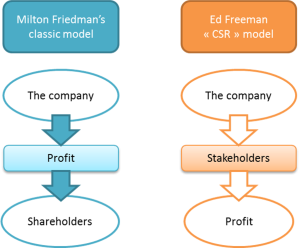

Shareholder theory states that, since managers of a firm get money from shareholders, the decisions of a business should pursue whatever gains the most corporate cash for purposes approved by the shareholders. As Milton Friedman wrote, “There is one and only one social responsibility of business — to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profits so long as it … engages in open and free competition, without deception or fraud.” [31] Friedman argued that a corporate’s social responsibility is to earn its shareholders a profit. The Council of Institutional Investors to the Roundtable 2019 said shareholders are not business owners nor providers of capital: “Accountability for everyone means accountability to no one.” The outcome seemed to be deeper economic inequality and insecurity, a sluggish response to climate change, and weakened governmental institutions. [32]

The Stakeholder Theory, a branch of corporate ethics, tackles morals and values in organizational management. This theory was first described in depth by R. Edward Freeman in 1984 on the notion that a company should provide value for all parties involved, rather than only focusing on shareholders. It emphasizes the interdependent connections between a firm and its customers, suppliers, workers, investors, communities, and other stakeholders in the organization. [33]

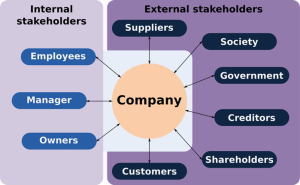

Below is a visual of potential audiences of a CSR report as well as a differentiation between shareholders and stakeholders:

A circle, labeled “company”, is in the middle, with other circles pointing toward it, making a larger circle all together. “Internal stakeholders” is on the left, with “employees, manager, and owners” beneath it, all pointing toward the center circle labeled “company.” “External stakeholders” is on the right, with “suppliers, society, government, creditors, shareholders, and customers” all pointing to the same circle labeled “company”.

Below is a visual of Milton Freidman’s classic model compared to Ed Freeman’s “CSR” model.

Corporate responsibility and ethics don’t have to be mutually exclusive. Adopting a stakeholder perspective when communicating environmental sustainability practices may enhance accountability and openness among large corporations and enhance consumer safety. Furthermore, it serves as a pathway to establishing positive public relations. To guarantee the firm gains and sustains momentum, the management must align the interests of the stockholders and all shareholders. This concept is often known as the “shared value opportunity”.

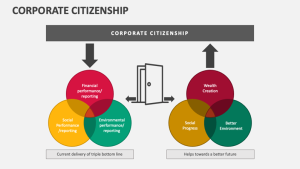

Corporate citizenship refers to a company’s responsibility to contribute positively to society while conducting business ethically and sustainably. According to Mirvis and Googins (2006), effective corporate citizenship involves a progression from basic legal compliance to innovative leadership in addressing environmental challenges. Companies that embrace this model do not just measure success through financial performance but also through their contributions to social progress and ecological well-being. This shift encourages businesses to act not only as economic entities but also as agents of systemic change. By investing in sustainability, transparency, and equity, businesses foster trust, enhance brand value, and help build a more just and livable future. [37]

The Effective CSR

There tend to be two ends of the CSR spectrum: one of which represents the very conceptual and aspirational, long on vision, but short on execution… and the other which tends to take a more accounting-like view of reporting, simply laying out the numbers, without emotion, context, or philosophical underpinnings.

Upon reading many CSRs, you may begin to see that some seem to just flow. They’re interesting, they’re charming, they have aspiration and vision, but are also practical and show vulnerability. You may find you feel a certain bond to the brand after reading it. In fact, there is a case to be made that the purest expression of a brand may not lie in its advertising, but in its sustainability report. Advertising talks at you, but many times, sustainability reports talk to you. We may consider five facets of an effective CSR as a lens through which to not only critically evaluate the content of a sustainability program, but also how it is presented.

VISAS: Five Facets of a Compelling and Practical CSR

Critical Analysis of Certifications and Standards

The explosion of the sustainability practice has come with a number of certifications and companies with creative, interesting, and compelling public faces. When examining potential standards for your organization or the claims of others, it can be useful to consider the following:

- What is the peer group? In essence, what organizations are supporting the standard and what are the resulting filings/reports/outcomes? While not perfect, it can be very useful to watch the moves that highly respected, and importantly, third-party verified sustainability leaders are making in regard to environmental standards.

- Are organizations making it a requirement of their own supply chains?If a company requires suppliers to be certified to an environmental standard, chances are they have quite a bit of interaction with it and believe it has an important role. One caution here is that these certifications can be in vogue on an industry basis. For example, conflict mineral standards are emerging as a significant concern in electronics, but are barely on the radar of many other industries not using these materials.

- Are audits and reports public? In many cases, the results of third party audits of the standards are made public, and these can provide an excellent view into how rigorous a standard is in practice. Metaphorically, think of certifications as a physical; if all that is being reported in the report is “blood pressure and heart rate,” we could expect the doctor is not terribly concerned with the well-being of the patient.

- Who can you talk to? One thing to remember is that those in the sustainability practice tend to be very highly engaged, though perhaps time- and resource constrained. If you are interested in a standard or choosing between competing standards, find a small handful of sustainability peers at organizations utilizing the standards and get in contact [39]

[1] Society for Consumer Psychology. “Good Guys Can Finish First: How Brand Reputation Affects Extension Evaluations.”

[2] Walter, G., Knizek, C., von Koeller, E., O’Brien, C., Hardin M. E., Young, D., Orimo, M., & Cordes, F. (2020). Your Supply Chain Needs a Sustainability Strategy. BCG. https://bcg.com/publications/2020/supply-chain-needs-sustainability-strategy

[3] What is ESG Investing? (2024, March 21). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/environmental-social-and-governance-esg-criteria.asp

[4] Brightest. (n.d.). Brightest | Helps You Help Others. Brightest. https://www.brightest.io/

[5] Bäckström, C., Lennartsson, J., Sayutina, A., Amouzgar, K., Taylor, A. ., Wang, W., Fathi, M., Mahon, K., Dahlberg, G. M., & Tursic, A. (2024). Sustainability Based on the Sustainable Development Goals.OER Commons. https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/33842/overview?section=3

[6] Brightest. (n.d.). Brightest | Helps You Help Others. Brightest. https://www.brightest.io/

[7] The Enhancement Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors. (2024). Securities and Exhcnage Commission. https://www.sec.gov/files/rules/final/2024/33-11275.pdf

[8] Brightest. (n.d.-b). Sustainability Measurement – How to Measure Environmental Performance. Brightest. https://www.brightest.io/sustainability-measurement

[9] Floyd, K. & Cardon, P. W. (2024). Business and Professional Communication (2nd edition). McGraw Hill.

[10] Hodge, K., Subramaniam, N., & Stewart, J. (2009). Assurance of sustainability reports: Impact on report users’ confidence and perceptions of information credibility. Australian Accounting Review, 19(3), 178–194.

[11] Baier, C., Göttsche, M., Hellmann, A., & Schiemann, F. (2021). Too Good To Be True: Influencing Credibility Perceptions with Signaling Reference Explicitness and Assurance Depth. Journal of Business Ethics, 178(3), 695–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04719-7

[12] Maroun, W. (2020). A conceptual model for understanding corporate social responsibility assurance practice. Journal of Business Ethics, 161, 187–209.

[13] Bussgang, J. (2022, November 22). Why Startups Should Embrace Radical Transparency. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2022/11/why-startups-should-embrace-radical-transparency

[14] Dalio, R. (n.d.). Principles by Ray Dalio. https://www.principles.com/

[15] Dahl, R. (2010). Green washing: Do you know what you’re buying. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118, A246–A252.

[16] Chen, Y.S., & Chang, C.H. (2013). Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. Journal of Business Ethics, 114, 489–500.

[17] Kenton, W. (2024, May 24). Triple Bottom Line. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/t/triple-bottom-line.asp

[18] Why sustainability is crucial for corporate strategy. (2023, October 6). World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/06/why-sustainability-is-crucial-for-corporate-strategy/

[19] The sustainability imperative – NIQ. (2021, May 3). NIQ. https://nielseniq.com/global/en/insights/analysis/2015/the-sustainability-imperative-2/

[20] Ames, C. (2022, January 22). What Is a “Conscious Business?” (as Defined by a Conscious CEO). Cory Ames. https://coryames.com/conscious-business/#:~:text=Leadership%20development,in%20the%20face%20of%20opposition.

[21] Pandey, M. (2022, January 1). Conscious capitalism re-inventing PR – The Mavericks – Medium. Medium. https://medium.com/the-mavericks/conscious-capitalism-re-inventing-pr-7de784edaa0f

[22] https://www.aflac.com/docs/about-aflac/csr-survey-assets/2019-aflac-csr-infographic-and-survey.pdf

[23] Cox, T. A. (2019). How Corporate Social Responsibility Influences Buying Decisions. Clutch Report. https://clutch.co/resources/how-corporate-social-responsibility-influences-buying-decisions

[24] Our Organization – Conscious Capitalism, Inc. (2024, January 12). Conscious Capitalism, Inc. https://www.consciouscapitalism.org/organization

[25] James, A. (2023). Regulatory and Public Influences. Sustainability Driven Innovation. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/ba850/node/637

[26] Brightest. (n.d.). Brightest | Helps You Help Others. Brightest. https://www.brightest.io/

[27] James, A. (2023). Environmental Standards and Certifications. Sustainability Driven Innovation. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/ba850/node/5

[28] Brightest. (2024, January 2). Top 7 Sustainability Reporting Standards – Comparing Disclosure Frameworks. Brightest. https://www.brightest.io/sustainability-reporting-standards

[29] Elkington, J. (2004). The Triple Bottom Line: Does it All Add Up? Chapter 1 Enter the Triple Bottom Line. https://www.johnelkington.com/archive/TBL-elkington-chapter.pdf

[30] https://www.brightest.io/sustainability-reporting-standards

[31] M. Friedman, “Capitalism and Freedom” (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 133.

[32] spidermak.com/en/ed-freeman-and-his-stakeholder-theory

[33] Stakeholder Theory. (n.d.). http://stakeholdertheory.org/about/#:~:text=About%20the%20Stakeholder%20Theory&text=The%20theory%20argues%20that%20a,values%20in%20managing%20an%20organization

[34]Business Stakeholders | Introduction to Business [Deprecated] |. (n.d.). https://www.coursesidekick.com/business/study-guides/wmopen-introbusiness/business-stakeholders

[35] Agwu, E. (2019). Impact of Stakeholders’ Analysis on Organizational Performance: A Study of Nigerian Financial Organizations. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3484381

[36] Porter, M., E., Hills, G., Pfitzer, M., Patscheke, S., & Hawkins, E. (2011). Measuring Shared Value: How to Unlock Value by Linking Social and Business Results. HBS. https://www.hbs.edu/ris/Publication%20Files/Measuring_Shared_Value_57032487-9e5c-46a1-9bd8-90bd7f1f9cef.pdf

[37] Mirvis, P., Googins, B. K. (2007). Stages of Corporate Citizenship: A Developmental Framework. IEEE Engineering Management Review, 34(3): 145-155. DOI:10.1109/EMR.2006.261390

[38] Corporate Citizenship. (n.d.). Collidu. From https://www.Stagecollidu.com/presentation-corporate-citizenship

[39] James, A. (2023). Environmental Standards and Certifications. Sustainability Driven Innovation. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/ba850/node/5