Chapter 6 – Diversity and Ethics in Leadership

Let’s begin by exploring the definitions of diversity and ethics, and how they work together to create a leadership culture within an organization.

You’ve probably heard and read about “DEI Initiatives” in the workplace. DEI stands for “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion,” and is a common buzzword and popular topic in today’s corporate culture. In fact, we use these terms so interchangeably that it’s easy to forget the subtle differences among them, and the nuances of practice attached to each. So let’s explore.

Let’s start with Diversity

“Diversity” is a word we hear almost daily, and we are constantly reminded of its importance. But what is it, exactly? Is it related to race and ethnicity? To abled/disabled status? What about a variety of religious and political ideas – do those contribute diversity to a group? Can a group of all women, a group of all men, a group of all Republicans, a group of all Democrats, contain diversity? Diversity is one of those concepts that the more you think about it, the more it expands. In American culture, when most people talk about forming a “diverse workplace,” they’re usually thinking about race – race seems to be our default definition. We assume that people of different races bring different experiences to the group, and indeed they do. The lived experience of being embodied in different ways is an important part of human identity. Due to this tendency to focus on race, it’s easy to forget the other types of diversity, such as people of varying religious and political viewpoints, and what they might contribute to organizational culture.

So diversity is about more than race – but it’s still largely about race. Diversity initiatives in the workplace can be traced back through our country’s history to the institutionalized discrimination of the Civil War, Jim Crow laws, and the various phases of the Civil Rights movement. People of color have been underrepresented in the American workplace for decades, particularly in universities and in corporate positions of leadership. Many diversity hiring initiatives seek to create a workforce that mirrors the population from which it draws its employees – for example, in the percentages of different demographics hired. Others complain that such initiatives might lead to quota-filling.

Reflect: How would you define workplace diversity? Have you been a part of an organization that had formal diversity initiatives, and what did those look like? What was the general consensus about them? As a leader, how would you encourage or incentivize followers to value diversity?

What about Equity?

Now let’s turn our attention to the word “Equity.” What does it mean for a leader to treat all followers equitably? Is that the same thing as equal treatment? As fairness? Let’s explore.

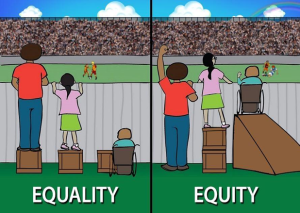

To begin, consider this popular drawing:

Here we see three people trying to watch a ball game over a fence. In the spirit of equality, they have each been given a wooden box. Does this enable all three of them to see the game? The person on the left is standing on the box and can see over the fence, but they are tall enough that they could have seen anyway. The person in the middle can just see over the fence while standing on tiptoe on top of their box. What about the person on the right, who is seated in a wheelchair? The box is no help. Even if it were possible to lift the wheelchair atop the box, this person would still be unable to see. But all three of these people have been given equal treatment. Did equal treatment accomplish the leader’s goal?

Now let’s examine the picture on the right. The first person can see over the fence without a box, so their box has been given to the middle person, who can see much better when standing atop two boxes. And our friend in the wheelchair has been provided with a ramp that allows them to sit at the same height as their companions, and to see over the fence. In this scenario, all three people can now watch the game, but take note that each of them needed different accommodations to be able to do so.

The drawing provides us with important insights as to how leaders should think about equity. Treating all followers equally doesn’t necessarily make the workplace equitable. A follower with vision problems might need a bigger computer screen than his colleagues, or someone with mobility issues might need a workstation to be reconfigured to allow for their challenges. In each of these cases, by accommodating the individual follower, the leader is giving them an equitable chance for success.

Privilege is also an important consideration when thinking about equity. According to McIntosh (1990), privilege takes the form of an advantage that you possess, but did not earn. For example, being attractive gives you privilege. Being born into a family with adequate financial resources gives you privilege. Having access to good schools gives you privilege. The article White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack by Peggy McIntosh provides a long list of these privileges, such as growing up with lots of books in the home, belonging to a mainstream religion or political party, and being raised by both parents.

The effect of privilege on equity, or the idea of “an even playing field,” can be illustrated by an exercise performed in many college courses. The instructor places an empty wastebasket in the center of the room. Class members are asked to crumple up a piece of paper, then come stand in a circle around this basket, with their crumpled paper in hand. The object of this exercise is to throw their paper into the basket. Easy, right? But wait – there are a few adjustments to be made. Participants are asked to take a step back, away from the basket, if they answer yes to a question, such as not being white, not being cisgender, or having to work full-time while going to school. Participants may also step forward if they belong to privileged social groups. After several rounds of stepping forward and backward, everyone throws their paper toward the basket. The most privileged members of the group are standing right over the basket at this point, and their task is easy. Others are standing at the outskirts of the room and have to throw a long distance – and usually miss.

We have equality in this situation – everyone is given the same task to complete. But equality is eroded by lack of privilege, and we slowly come to see that the task is not the same at all when the complications of privilege are introduced. This is the instructor’s moment to lead the class in a deep reflection of the exercise.

Reflect: What are your thoughts on the concepts of equality and equity? What can a leader do to facilitate equity among followers? What if followers find it unfair? Have you been part of an organization where these issues were a challenge? How did the leader handle that challenge?

And now, Inclusion

What comes to mind when you hear the word “inclusion?” In some ways, it’s a comforting word, conjuring visions of being warmly welcomed into a community. But the concept of inclusion also implies exclusion, or shutting others out of the group. The act of exclusion implies “This is my turf, and you’re not welcome here.” Who gets to decide who is included, and who is not?

It’s important for leaders to foster a culture of belonging within the organization. The word “belonging” is preferable to “inclusion” in this context, because it emphasizes the idea of working in community with others, rather than the idea that the workplace is the territory of some and not others. Leaders can nurture this idea of belonging by mixing up work groups to expose followers to a variety of others, by encouraging the sharing of ideas without judgment, and by creating a friendly social atmosphere through non-work activities.

According to the Vertical Dyad Linkage Model (Dansereau et. al., 1975), which served as the foundation for Leader-Member Exchange Theory, followers develop high levels of trust and feelings of inclusion within an organization when they perceive an “in-group” relationship with their leader. This means they perceive the leader to like them, accept them, and consider them worthy of respect and influence. They feel that the leader is compatible with their followers in terms of values and personality. Followers who perceive having this in-group relationship with their leader may be willing to work extra hours or take on new projects because they have faith and trust that the leader is concerned with everyone’s well-being.

Reflect: Can you think of an organization that made you feel included? What about excluded? What did the leader do to manage this culture of being “in” or “out?” As a leader, what would you do to foster a sense of belonging among your followers?

Let’s talk about ethics

Ethics is a tricky word, as many people use the term interchangeably with “morals” – but morals and ethics are different. Moral values are usually personal and tied to an individual’s sense of right and wrong, often rooted in their upbringing and the values of subcultures such as political and religious views. Ethics, on the other hand, are a contextual set of behavioral standards, and can vary in different organizational situations (see Martinez et al., 2021). For example, an individual may personally believe that gambling is morally wrong but may happily sell raffle tickets for a charity on behalf of their workplace, in support of the organization’s ethic of being a positive force in their community. You might think it’s immoral to bribe someone into doing business with you, yet you’ll “wine and dine” them to persuade them to sign a contract with your organization, because this practice is common in your business. Within the context of your organizational mores and processes, it is ethical.

While many leaders commit to acting ethically, the path to an ethical decision is not always clear. The leader will consider their own personal moral values, the mission and vision of the organization, the particulars of the context and situation, and the expectations of the larger culture in which they are doing business. When weighing all of these factors against each other, it is useful to be guided by an ethical principle, such as utilitarianism, the categorical imperative, altruism, or servant leadership. Let’s examine each of these ethical principles and consider how to best apply them in different situations.

Four ethical principles

Utilitarianism

Traditionally attributed to John Stuart Mill, the principle of utilitarianism can be summarized as “doing the greatest good for the greatest number” (Driver, 2022). The correct action to take in any situation can be decided by evaluating its possible consequences, and the proportion of people who will be affected by those consequences. When deciding on “the greatest good,” it is useful to define what is meant by “good” in a given context.

For example, should we define “good” as the choice that will bring the most people the most pleasure? The least amount of pain? Is it the choice that will distribute resources in the most equitable fashion possible, or rather, the choice that will allocate the largest amount of resources to those who are in my favor?

Leaders often choose to apply this ethical principle in the workplace, especially in times of limited resources. How can the leader allocate those resources in a way that will maximize happiness (or minimize misery) amongst followers? How can the leader ensure that this choice will also meet with the approval of higher-ups? For example, consider a situation in which the salary budget must be cut, and the leader faces a situation where staff layoffs are inevitable. The leader must weigh the costs and benefits of all options, and choose the course of action that maximizes the outcome for the largest number of people. These constituents will include not only the affected employees, but their families, the organization’s stakeholders, and those who are allowed to stay. Unhappiness and hurt are inevitable for some parties, and the leader must also plan to manage the related cultural change in the workplace.

Categorical Imperative

The categorical imperative (Kant, 1785) can be defined as an absolute requirement that should be obeyed in all circumstances, regardless of context. Kant would argue that humans have concrete obligations to one another that are not a matter of personal belief or situational factors, but rather, apply universally to all members of the human community. We have a “perfect duty” to one another and should adhere to it under any and all circumstances.

For example, “don’t kill another human” could be considered a categorical imperative – something we should not ever do, no matter what the circumstances. Even if this person is evil, or about to kill you, the imperative would dictate that for you to kill them would be immoral and unethical. We can see this attitude in our own world in people who think that war is absolutely wrong, whatever the circumstances that prompted it. Another example is a person who is willing to die for their beliefs, rather than to renounce them.

Another example of a categorical imperative would be “you must always tell the truth – it is always wrong to lie.” I imagine you can think of circumstances where lying might be justified, but the ethical principle of the categorical imperative would say that circumstances do not matter; lying is inherently wrong, no matter why it’s done, even if I’m planning to give you a surprise birthday party.

Consider the challenges a leader might face under this guiding principle. Imagine you are director of a department. Your supervisor has told you that the company is about to be sold to another owner, but this information must be kept absolutely quiet so it doesn’t cause panic among employees or affect the stock price. One of your favorite followers comes to you and says they have heard a rumor that the company is about to be sold – is it true?

You’re the leader – how do you respond? If you are guided by the categorical imperative, you would believe lying is absolutely wrong. You’ve been asked a direct question, and you have the answer, but you were given that information in confidence. Sharing it might cost you your own job. What to do? You might claim you don’t know, but that would be a lie. You might change the subject, but steadfast adherents of the categorical imperative might even say that hedging or dissembling is a form of lying. This ethical principle, then, is particularly difficult for most of us to live by, especially as titled leaders.

Altruism

You are probably familiar with the term altruism, which was coined by Auguste Comte in the nineteenth century (Comte, 1852). An altruist lives for the sake of others and makes decisions in order to benefit others without regard to oneself. The ethic of altruism would dictate that we only consider the consequences of our decisions on those around us and disregard any consequences to ourselves. Be kind, be nice, be outward-focused, and put others first in your thought processes.

What does this mean for a leader? A leader who is guided by the principle of altruism is going to live for their followers and do everything to benefit others. For example, suppose you are the leader of a restaurant crew, and you are short one person on the closing shift tonight because someone called in sick. You could call in another employee, or make everyone stay late, but you feel this would be unkind and inconsiderate to your staff. Therefore, you send everyone else home on time, and you stay late, mopping floors and sanitizing bathrooms, so that your followers can get home to their families.

Or consider a workplace that has always provided a free restaurant lunch for the whole department when it’s someone’s birthday, but now, because of budget cuts, upper management is no longer willing to bear this expense. As the leader, you dread telling your staff about this budget cut. What do you do? The altruist might continue to pay for these meals, out of their own pocket, so as not to disappoint their followers. These large restaurant bills might take a big portion of the leader’s monthly paycheck, but still – it’s the nice thing to do.

The altruist must guard against being taken advantage of, or being seen as a “doormat.” Pure altruism is a difficult principle for anyone to follow, and especially challenging for a leader, who must please multiple constituencies. Can you make your employees, your bosses, and your customers all happy at the same time? Are you willing to sacrifice any pleasure or happiness for yourself in the process? Many of us would take a more practical approach – which is described in the next section on servant leadership.

Servant Leadership

Servant leadership (Greenleaf, 1997) is the principle that leaders should be focused on nurturing the growth of their followers, rather than on accruing power or control for themselves. It differs from altruism in that altruism is motivated by self-sacrifice, whereas servant leaders are focused on developing the skill sets and job satisfaction of followers. The servant leader views each follower as an individual and takes a sincere interest in what that follower needs in order to feel respected and valued. This type of leader will identify the areas of potential in a follower and will mentor (or arrange mentorship for) that follower so that the follower might advance in the organization.

An important principle of leadership is that leaders play a large part in setting the culture in an organization. The servant leader will seek to create a culture of trust and respect and will foster the leadership skills of others so that they, too, may become persons of positive influence. Servant leaders often take a participative approach and consider themselves as part of a team. While they may be the “first among equals,” possessing skill and authority that others do not, servant leaders strive to value each follower with respect and sincerity. The servant leader is your “coach” who will help you climb the hill, developing the skills you need to succeed.

The participative approach of the servant leader often includes involving the follower in setting their own performance goals, as well as including all stakeholders in creating a vision and mission for the group. The approach is not “Here’s what I’ve decided you have to do,” but rather, “What goals should we pursue? How should we frame those goals? What are our collective skills that we can use in fulfilling these goals?”

The practice of servant leadership has some potential downsides. For example, if your own boss/leader has a more authoritative style, they might consider your servant leadership habits to be ineffective or weak. Under a servant leadership style, decisions can take longer to make, as the leader is focused on including others in the process. This inclusion, plus the desire to develop followers’ individual skills, can make this style of leadership quite time-consuming.

What are your thoughts about servant leadership? Have you ever had a leader who focused on developing followers so that the followers could reach their highest potential? How did this leader affect your workplace culture?

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have examined diversity and ethics in leadership. We considered the similarities and differences among diversity, equity, and inclusion, and the role of leaders in fostering these values in an organization. We also evaluated the role of ethical considerations in leadership and took a deeper look into four ethical principles that often guide our choices.

Chapter Resources

Critical Incidents in Leadership

Does ethics matter when judging professional accomplishments? In this article: https://www.washingtonpost.com/food/2023/05/12/james-beard-awards-chef-hontzas-ethics/ we read about an Alabama chef named Timothy Hontzas, who was being considered for a James Beard Award. The Beard awards are a top honor in the food media and restaurant chef community. The Beard organization requires candidates to have a “demonstrated commitment to racial and gender equity, community, environmental sustainability, and a culture where all can thrive.”

In your opinion, does Chef Hontzas meet this criterion? Should the award focus on professional accomplishment without this ethical component? What is the purpose or advantage of including these ethical requirements?

Leadership Communication in the Media

- Many organizations have begun hiring “Chief Diversity Officers,” who are charged with ensuring that best practices for DEI are being followed in the organization. Learn more about this important leadership role here: https://globalyouth.wharton.upenn.edu/articles/college-careers-jobs/the-work-of-chief-diversity-officers-dei/

- Is artificial intelligence (AI) such as ChatGTP an ethical threat in the fields of business and education? In this podcast episode, Boston University ethics professor David Epstein examines the pros and cons of AI, and how it is poised to change the classroom and workplace: https://www.bizjournals.com/boston/news/2023/04/27/ethics-professor-raises-key-questions.html