Chapter 3 – Historical and Contemporary Views of Leadership

In this chapter, we will examine how leadership was viewed in the past, and how it is understood today. We will also explore a variety of perspectives on leadership such as Authentic, Transformational, and Servant Leadership; as well as Traits, Situational, and Functional Leadership.

Historical Views of Leadership

What do followers want and need? What is fair compensation? And how much supervision and direction does the average employee require? To answer these questions, we need to reflect on the origins of the study of leadership communication, which began in the early days of the manufacturing industry. With the dawn of the assembly line and the modern factory, a new type of workplace structure emerged: The need for one man (it was almost always a man) to supervise many others, ensuring that they followed correct procedures and achieved maximum efficiency. But how was this to be done?

A leader might have chosen to take a “Theory X” approach (McGregor, 1960), and see followers as having a dislike for work, and a need to be closely supervised in order to control their work outputs. According to this view, followers might even need coercion or punishment in order to work effectively. Think about docking an employee’s pay, making them work longer hours, or threatening their position in the organization. A Theory X leader believes that followers lack ambition, and their main motivation is the wages they will be paid.

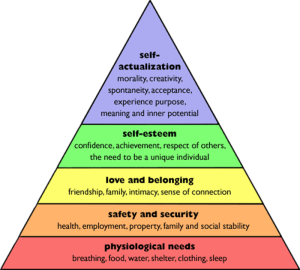

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs provides a useful model for examining the Theory X approach. According to Maslow (1943), each of us needs a number of resources in order to live a happy, healthy life, and these resources can be arranged in order of importance. This list of needs is often arranged in a picture of a pyramid, with the lowest-level needs at the bottom, and the highest-level needs at the top. The principle of the Hierarchy is that our lower-level needs must be met before we can advance up the pyramid and address our higher-level needs. When you examine the pyramid, you can see that the Theory X leader will focus on the lowest two levels of the pyramid: physiological needs, and safety and security. The Theory X leader would believe that their obligation to followers is confined to making sure they have a reasonably safe and comfortable workplace, and are paid for their labor. The leader has no obligations beyond that – they are not concerned with your mental or emotional health, opportunity for advancement, or feelings of connection with others. As long as you are paid in exchange for your labor, the thinking goes, you should have nothing to complain about.

That might be a valid perspective for those who have a transactional view of work and it certainly illustrates the historical view of leadership quite well. The leader must enforce proper procedures and ensure efficiency – maximum number of widgets produced – and the follower must be watched carefully to ensure they are earning every penny of their wages. Many leaders still think this way, but the contemporary view of leadership incorporates further levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy. Let’s look at the pyramid again:

Experienced leaders know that their followers’ lower-level needs must be met before they can perform at their best. For example, if a person is physically uncomfortable, they may not be able to perform at a high intellectual level, so ensuring a comfortable workplace will contribute to each follower giving their best performance. Similarly, if a follower does not feel safe on the job, they may hold back on the level of effort they are willing to give to their job tasks. The most successful leaders will work to ensure maximum feelings of comfort, safety, and belonging in the workplace, knowing that establishing these basic feelings of security will allow followers to turn their attention to performing at their highest level.

Let’s turn our attention to the “Theory Y” leader, then.

Contemporary Views of Leadership

The “Theory Y” leader assumes that there is a cooperative relationship between leaders and followers, and that followers find fulfillment in their work. Once lower-level needs are met, followers can continue to climb the pyramid, finding many of its resources in the workplace; for example, a sense of connection through positive relationships with coworkers, and self-esteem through being acknowledged by others for their good work. The Theory Y leader is interested in developing followers and helping them to grow, both personally and professionally, and will look for ways to nurture their climb up the pyramid. The Theory Y leader hopes followers will like their work, and find it nourishing to all aspects of their lives.

This isn’t to say that all contemporary leaders think this way. There are a lot of “Theory X” types still in the workplace, and some of them achieve effective results. But as you learned in the previous chapter about leader-member relationships, leaders nowadays usually focus on individual team members and believe that you get the best work out of your followers not by browbeating them, but by nurturing their development and the achievement of their personal goals.

Now let’s turn our attention to some leadership perspectives that emerge from these contemporary attitudes toward leadership.

Authentic, Transformational, and Servant Leadership

Authentic Leadership

We’ll start with a look at Authentic Leadership (see Luthans & Avolio, 2003). What does authenticity mean to you? Most people think it means that a person is genuine, honest, and behaves without pretense; they are confident in being who they are, and they know what they stand for (and so do you). By extension, we would say that an authentic leader is someone who behaves rationally and honestly with followers. This leader has guiding principles and lives by them. They have formed these guiding principles by deep reflection on their own successes, failures, and personal values. Their behavior is predictable because we know what they believe and what they are trying to achieve for themselves and for the organization. These leaders model an example for others and prioritize follower development. If you have a leader who encourages everyone to focus on the organization’s mission and vision, who does so themselves, and focuses on acting with integrity in all circumstances, you have an authentic leader.

Reflect: How many authentic leaders have you known? How did their followers feel about their leadership? Were they effective leaders?

Transformational Leadership

Now let’s examine Transformational Leadership. What does it mean to transform someone or something? The most common definition would be to change something into something else, usually for the better – in other words, to change a lower-level item into a higher-level version of itself. Using this definition, we can begin to understand a transformational leader as a leader who is able to guide and shape followers into being better versions of themselves. According to Diaz-Saenz (2011), transformational leadership is “the process by which a leader fosters group or organizational performance beyond expectation by virtue of the strong emotional attachment with his or her followers combined with the collective commitment to a higher moral cause” (p. 299).

Reflect: Have you known a leader who cultivated strong individual relationships with each follower, and sought to develop their skills? What behaviors did they exhibit that showed followers they were truly interested in them?

Servant Leadership

Now, let’s look at Servant Leadership. At first glance, “servant leadership” might seem like a contradiction in terms. How can a person be a servant and a leader at the same time? Greenleaf (1998) explained a servant leader is not motivated by power, but rather, by bringing out the best in their followers. This leader wants to make sure that their followers are fulfilling their highest priority needs, to the greatest extent possible. The servant leader is focused on the highest levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy, putting themselves in service to their followers’ aspirations and goals. The servant leader cares deeply about the growth and well-being of every follower in the workplace.

Reflect: Have you known a servant leader? How did this person put themselves into service of their followers? Do you think this kind of leader is strong and influential, or in danger of being perceived as weak?

Now that we’ve examined these three types of leadership, let’s ask ourselves: Could the same person be all three kinds of leaders in one? Could you be an authentic, transformational, and servant leader? Your authors believe that you can, and in fact, all three types of leaders share certain characteristics. Like the authentic leader, they all exhibit personal integrity. Like the transformational leader, they seek to develop and improve their followers. And like the servant leader, they accomplish this development through individual attention to each follower’s goals and needs. A leader who exhibited all of these qualities would be a delight for most of us to work with.

Traits, Situational, and Functional Leadership

We began this chapter by examining some historical attitudes about leadership. Leadership qualities were once thought to be innate; in other words, something a person was born with, or that was just part of their personality. According to this view, some people are leaders, and others aren’t. What do you think? Do you believe there are “born” leaders? Or is leadership exclusively a learned skill? Or might it be a combination of innate characteristics and learned behaviors?

Let’s explore these questions.

The Traits Approach

The traits approach to understanding leadership focuses on the personal attributes of the individual in the leadership position. It assumes that people with certain traits will exhibit behaviors that will enhance their leadership effectiveness (see Fleenor, 2006). What personal qualities do you associate with leadership? In U.S. culture, we are usually taught to believe that leaders must be assertive, outgoing, and decisive (it also helps if you are tall and good-looking!) Credentials help too. If the individual has an extensive background in a particular area, or specialized certificates and degrees, we might expect them to be good leaders. A person who is intelligent and adaptable to change might seem to have leadership potential.

Contrarily, if we encounter a person who seems timid, soft-spoken, or indecisive, our cultural conditioning could lead us to assume that they would be a poor leader. It’s important to recognize that this assumption is heavily based on what we have been taught. In some parts of the world, followers value a leader who takes their time to make important decisions, or who exhibits a gentle demeanor. In her book Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking (2012), author Susan Cain explains that we may be too quick to judge quiet and introverted people as having poor leadership potential. She points out that Rosa Parks and Martin Luther King, Jr. were both important leaders in the U.S. civil rights movement, but Parks was an introverted and unassuming individual, whereas King was outspoken and had a magnetic personality. Both of these figures had an important role to play, even though their personal qualities were quite different.

The traits approach to understanding leadership has risen and fallen in popularity over the years. In the early days of leadership study, traits were considered vital to an individual’s leadership potential. Over time, scholars came to believe that leadership was more of a learned skill, and traits were not as important.

Reflect: What do you think? How important are personal attributes – “traits” – to one’s leadership potential? Is leadership a learned skill? Can anyone become a leader?

The Situational Approach

The situational approach to leadership asserts that the techniques a leader uses to guide followers are always contextual, and depend heavily on the willingness and skill levels of the followers. In chapter 2, you learned about the Hersey-Blanchard model, which suggests that an effective leader must consider the level of willingness (desire to do the job) and skill level (beginner to advanced), and then craft a leadership plan that will best suit these followers. Hersey (1997) explains that situational leadership is about matching your leadership techniques to the needs and skills of each follower.

For example, a follower who is very willing, but low in skills, might benefit most from a leader who gives specific and individualized instruction. If this follower is unwilling, the leader might need to spend some time focusing on increasing the follower’s interest in the task. An unwilling but skilled follower may need convincing of the worthiness of the task. A follower who is both willing and skilled (which many leaders consider to be the very best kind of follower) is able to work independently. The leader can delegate tasks to this type of follower.

In his 1997 work, Hersey asserts that leadership has similarities to the practice of medicine; that the leader must diagnose the situation before “writing a prescription” (p. 8), and that to do otherwise is a form of malpractice.

Reflect: Think of a time when you were willing to do a task, but lacked the skill. What kind of guidance did you need from your leader (whether or not you received it?)

The Functional Approach

The functional approach to leadership focuses on leader behavior, particularly communicative behavior. According to this approach, leadership is more than just a role or a title, but manifests in a person’s actions. Zubeck (2020) asserts that leadership is a function of having and disseminating knowledge. As an example, consider this scenario: An accident occurs in the workplace, and one of the line workers steps forward and says “I know how to handle this situation. Here’s what we should do.” This person might not hold any kind of formal leadership position in the organization, but they are performing the functions of leadership through the way they are communicating.

Most of us have worked in a group on a class project, or in a team at our jobs. Oftentimes, these groups or teams start out as a collection of equals with no clear direction, then someone emerges as leader through saying “Here’s what I think we should do” or “Let’s divide the work in this way.” The other members of the group will often defer to this person’s guidance – they have put themselves forward as a leader through the way they communicate, whether or not they have any formal designation or title. Sometimes, the people who put themselves forward may not be the best leader for the particular context.

In chapter 5, we will examine leadership in groups and teams, and spend some more time with these leadership models.

Reflect: As a follower, have you experienced functional leadership? What was the outcome? What do you think of the assertion that leadership manifests in actions (particularly communication), rather than in one’s formal role or title?

Conclusion

In this chapter, we considered the history of leadership communication and examined a number of theories and models about leadership. Think about the kind of leader you would like to be, and the behaviors you need to develop. Work to increase your knowledge of your followers’ skills, needs, and attitudes, and the best techniques to lead them.

Chapter Resources

Critical Incidents in Leadership

Did you know that Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky began his career as an actor and entertainer? Prior to his 2019 political success, he was known primarily for his comedy, yet during his presidential campaign, the public came to see him as a politically informed and intelligent leader. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, he has become a household name around the world as an unexpected, emergent leader. According to Hosa and Wilson (2019), Zelensky came onto the political scene as a vocal outsider who appealed to voters who were ready for a change (read Zelensky Unchained: What Ukraine’s New Political Order Means For Its Future). Why do you think Zelensky was successful in securing the presidency? How did leadership communication play a part in his transition from actor/comedian to respected politician?

Leadership Communication in the Media

- How does an authentic leader navigate change? In this article about New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern (https://www.newsweek.com/intersection-resilience-authenticity-navigating-leadership-challenges-post-pandemic-world-1836231), author Joseph Soares asserts that authenticity and resilience go hand in hand for leaders. Ardern was leader of New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic, and gained notice for how well she managed crisis through concentrating on public health and securing the economy of her country. Reflect on this relationship between authentic leadership and the ability to successfully manage change. How can a leader cultivate resilience?

- How is it possible to be both a servant and a leader? Are service and leadership compatible? And should a servant-leader focus first on service, or on leadership? Read this essay by Greenleaf, which considers these questions (https://www.gonzaga.edu/news-events/stories/2023/9/26/robert-greenleaf-servant-leadership). Reflect on the ways you could combine service and leadership as a leader in your workplace, and the effectiveness of servant-leaders you have known. Consider the reasons why some leaders might consider leadership and service to be contradictory.