54 Historical overview of Christianity

Timeline of Christianity

- 63 BCE – Conquest of Judea by Rome; Herod crowned King of the Jews 40 BCE – 4 CE

- 4 BCE – 30 CE Life of Jesus

- 26-36 CE – Pontius Pilate rules Roman prefect of Judea

- c. 27-30 CE – Jesus’ ministry

- 30 CE – Jesus’ crucifixion

- 46 – 62 CE – Paul of Tarsus’ missionary work

- 70-90 CE – Synoptic gospels written (Matthew, Mark, Luke)

- 90 – 110 CE – Gospel of John written

- 312 CE – Christianity legalized within the Roman Empire

- 325 CE – Council of Nicaea

- 1054 – Split between Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Churches

- 1517 CE – Luther writes 95 theses, leading to the Protestant Reformation

Historical overview of Christianity

This historical overview is divided into three main time periods:

First-Century Judaism and Early Christianity: c. 6 BCE – 325 CE

- Religious and Social Characteristics of First-Century Jews

- Life of Jesus, Life of Paul of Tarsus

- Early Christian writings and communities

- Emperor Constantine and the Council of Nicea

- St. Augustine

From the Romans through Medieval Christianity: 325 – 1534 CE

- Split between the Eastern and Western Christian Churches

- The Roman Catholic Church

- Monasticism-Medieval theology: afterlife destinations

- The Eastern Orthodox Church

- The Crusades

From the Protestant Reformation to the Present: 1534 CE – present

- Martin Luther’s 95 theses

- Protestant theology

- John Calvin

- The spread of Christianity throughout the world

First-Century Judaism and Early Christianity: c. 6 BCE – 325 CE

Religious and Social Characteristics of First-Century Jews

Descendants of the Jews had been living in and intermittently ruling the regions of Judea and Galilee for centuries. In the first century CE, most Jews in this region lived in small villages. Jewish villages were organized around the Israelite religion of their ancestors. In this ancestral religion, the father was the financial and spiritual leader of the family. Through the guidance of the father, each household was made sacred through keeping the proper covenants with God. The land was also an important part of the religion of the village. Most villagers relied on the land for agriculture and herding animals to survive. The land took on a sacred dimension because the Jews believed that God promised it to them in return for honoring God’s covenant with Abraham (see Judaism chapter).

The main authority of Jewish life in first-century Judea and Galilee was the temple in Jerusalem. The Jews who lived as herders and agriculturalists in the surrounding villages were expected to make pilgrimages to the temple three times a year. Representatives from the temple visited the villages to ensure that the people living there were practicing Judaism correctly. A group of Jewish authorities known as Pharisees were responsible for making sure that the Jews were following proper religious practices. Since obedience to the secular power of the Romans was the price for religious freedom, the Pharisees were careful to make sure their fellow Jews followed the rules.

There were many social and political forces during this period that threatened the ancestral Israelite religion of the villages. The Romans imposed a system of taxation that threatened to take away the ancestral lands of the Jews. Also, the religious practices of the village were often at odds with the religion of the temple in Jerusalem. Many Jews anticipated a savior figure known as the messiah. Originally, the term messiah referred only to a king who would come and save the Jews from foreign domination. Over time, however, the messiah came to be envisioned as a spiritual leader who would lead the Jews back into a proper relationship with God.

During this period, many Jews claimed to be the messiah. The Romans in control of Judea and Galilee viewed those claiming to be a messiah as political revolutionaries, and often executed such people by crucifixion. The Romans appointed Jewish political figures to govern the provinces and monitor local activity in the provinces of Judea of Galilee. These appointed figures followed the leadership of Rome in deciding the fate of those claiming to be a messiah.

Historical Life of Jesus (c. 4-6 BCE – c. 30 CE)

Jesus was born in the village of Bethlehem sometime around 4-6 BCE during the reign of King Herod, and grew up in the village of Nazareth. He was born into a Jewish family as the eldest child, and received training in woodwork and carpentry. He and his family spoke Aramaic, a Near Eastern language indigenous to the region of Judea and Galilee. Aside from this basic outline, we are not sure about many of the details of Jesus’ childhood and development.

The events of Jesus’ life became more public after he began his ministry around the age of thirty. A preacher named John the Baptist attracted many through his practice of baptism, a spiritual purification ritual of being submerged in water. Jesus listened to the preaching of John the Baptist and was publicly baptized by him in the Jordan River. His baptism by John was a significant event for the future ministry of Jesus. It was through baptism that Jesus was sanctioned as a spiritually pure teacher – one who could rightfully claim that he was the messiah that the Jews had anticipated.

After his baptism, Jesus traveled throughout the countryside of Judea and Galilee. He gained followers, known as disciples, who viewed him as the messiah. These disciples claimed that he performed miracles including healing the sick. Jesus taught ethical action, such as the importance of caring for the poor. The early followers were mostly ordinary Jewish citizens of Judea and Galilee. Over the three years of Jesus’ ministry, the movement grew large enough to be considered a threat to the political authorities in Judea.

Many of the teachings of Jesus differed from those of the temple authorities in Jerusalem. Roman officials worried that the claim that Jesus was a messiah would bring about a rebellion. After three years of teaching, Jesus was arrested and brought before Pontius Pilate, an official of the Roman government. Pontius Pilate sentenced Jesus to death by crucifixion in approximately 30 CE.

Jesus’ disciples believed that after three days Jesus returned to life (resurrected) and spent time with them. During this time, he guided them on how to spread his message. According to their account, he then rose up (ascended) into heaven. A select group of disciples spread teachings of Jesus in Judea and Galilee.

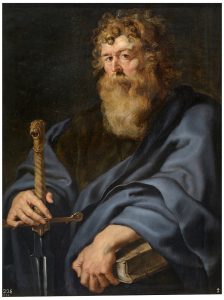

Paul of Tarsus: Spreading Christianity to the Gentiles

The early Christian movement was persecuted by both Jews and Romans. Paul of Tarsus (c. 5 CE – c. 64 CE) was a Greek-speaking Jewish Pharisee who passionately fought against the early Christian communities. However, a powerful conversion experience changed Paul and he soon became one of the most influential figures of Christianity. Paul argued that salvation was gained by faith in God and in Jesus. He interpreted the crucifixion of Jesus as an act of atonement for the sins of humanity which began with the disobedience of Adam and Eve. Paul could speak and write in Greek, so he was able to spread early Christian teachings beyond the Jewish communities to gentiles, meaning non-Jews. By converting gentiles, Paul was effective in establishing Christian communities throughout the Mediterranean region.

Paul wrote letters to early Greek-speaking Christian communities to guide them and resolve disagreements among the members. These letters, known as epistles, are included in the New Testament of the Bible. In these letters, Paul made it clear that Christianity was not just a reform movement within Judaism. Paul believed Christianity contained a universal message for all human beings. Because of Paul’s influence, Christianity expanded beyond Judea and Galilee, becoming an independent religion.

Early Christianity

For the first few centuries after the death of Jesus, the Christian movement remained small in number. Early Christians met in the houses of other Christians for worship. Often, these early Christians were persecuted by powerful religious and political forces. During this early period, many Christians were martyred, which means that they were killed for their religious beliefs. These martyrs became an important source of inspiration for Christians in later times.

During the third century CE, some Christians withdrew into the deserts of Egypt and Syria. Here, they practiced asceticism, which means extreme self-discipline and denial of bodily pleasures for religious reasons. Their goal was to have a deeper experience of God through restrictions on diet and social interaction and a concentration on prayer. These groups eventually developed their own rules of monastic behavior, including vows of chastity and poverty and lived a communal life dedicated to prayer and worship. This lifestyle combined the solitary tendencies of the ascetics with the communal ideal of a life dedicated to the service of God and the church. Later in Christian history, monasteries played a large role in the dissemination of the Christian message and in shaping a standard pattern of belief and practice in the Middle Ages.

Council of Nicaea (325 CE)

The status of Christians changed in 312 CE when the Roman Emperor Constantine decreed that Christianity be recognized as a legitimate religion. He was supposedly convinced of the merit of Christianity after he experienced military success when using the symbol of the cross in battle. Constantine granted Christianity legal status and protection under Roman law. By 384 CE, Christianity was established as the religion of the Roman Empire. Three years later, in 387 CE, the Christian canon was fixed. In a relatively short period, Christianity went from being a reviled fringe movement to the official religion of one of the most powerful empires in the world.

Once Constantine declared Christianity to be a legal religion in the Roman Empire, he realized that it was necessary to establish a consistent theology. At this time, there were many competing interpretations of what it meant to be a Christian. In 325 CE, Constantine organized a meeting in the city of Nicaea to gather all the leaders of the different established Christian communities throughout the empire. The result of the council was a creed, an official statement of belief. The Nicene Creed thus established a common agreement about the core beliefs of Christianity at the time. The Nicene Creed will be discussed in more detailed in the section on Doctrine in this chapter.

As Christianity spread throughout the Roman Empire, there were important developments in its theology. Theology means “the study of God”, and those who engage in theology are known as theologians. One of the most important theologians in the history of Christianity is Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430 CE). St. Augustine was a Christian religious leader who lived in Northern Africa, and he wrote about concepts that became very important for later Christian theology. One of his most important concepts was that of original sin-the idea that all human beings are born with the tendency to disobey God because of the sin Adam and Eve comitted in the Garden of Eden (for more information, see Narrative section). For centuries after his death, Agustine’s ideas influenced Christianity in important ways.

From the Romans to Medieval Christianity: 325 – 1534 CE

In the fifth century CE, Germanic tribes invaded the western half of the Roman Empire, leading to its collapse. This vast region included much of contemporary Europe. The eastern half of the Roman Empire survived for another thousand years. However, the physical distance between Rome and Constantinople helped to foster doctrinal differences in Christianity.

These differences in belief resulted in a major split in Christianity. The versions of Christianity practiced in the eastern and western parts of Europe grew further apart, evinced by artistic and ritualistic differences. In the year 1054 CE, the eastern and western Churches officially separated from one another. The western half of the former Roman Empire continued a tradition that would grow into the Roman Catholic Church. The eastern half, which was centered in Constantinople, came to be known as the Eastern Orthodox Church.

The Roman Catholic Church

With the fall of the Roman Empire in western Europe, an era of economic and political uncertainty ensued. Germanic tribes called the Franks had gained control of western Europe by the ninth century CE. The Franks supported the church in Rome politically. In return, the Church approved of their kings, and sent their clerics to work in the government. They also attempted to convert non-Christians in the kingdom.

The highest office in the Catholic Church was originally the bishop. Bishops were assigned to cities to oversee religious life. However, given the importance of the city of Rome to the Roman Empire, the bishop of Rome was given special prominence. This position eventually became a place of centralized authority: the leader of the Roman Catholic Church came to be known as the Pope. He occupied the highest position in a hierarchy of religious leaders that included priests, bishops, and cardinals.

For many people in Medieval Europe, the Roman Catholic Church became the central authority in all matters of religion. This authority extended to most aspects of daily life. Until the twelfth century CE, the Roman Catholic Church cooperated with local rulers for the most part. In the twelfth century, however, Pope Innocent III (reigned 1198 – 1216 CE) changed the power balance with the aim of unifying the Christian world under the Pope. As the Pope consolidated political power, the Church tried to stamp out heresy by establishing a specialized court known as the Inquisition. During the Inquisition, heretics, meaning people holding opinions at odds with established doctrine, were confronted by this court and forced to recant their errant beliefs, or face harsh punishment, including death for the most egregious crimes.

Monasticism

Some Christians in the third century CE had gone into the deserts of Egypt to practice asceticism. These Christians formed monasteries, communities dedicated to prayer and worship of God, and set forth strict rules for behavior. Those who lived and worked in monasteries were known as monks. Part of being a monk involved taking a vow of celibacy and poverty and devoting one’s life to contemplating Christianity. The female counterparts of monks are known as nuns, and they live in communities known as convents.

Monks and nuns of the Middle Ages lived by a strict daily schedule that included praying, reading the Bible, and working at various chores. Benedict of Nursia (c. 480 – 540 CE) compiled the Benedictine Rule, an official list of rules for monks and nuns to follow. He also established a hierarchy of authority within the monastic community that was adopted by many monasteries throughout the Christian world during the Middle Ages. The ideal of poverty and service was embodied by religious figures later in the Middle Ages such as Francis of Assisi (c. 1182 – 1226 CE), who gave up a life of luxury to establish the Franciscans, an influential Christian order dedicated to poverty and charity.

Monasteries were a central economic unit of medieval towns and performed many functions, including feeding the poor, providing housing for travelers, and producing goods. Monasteries were also centers of learning that produced, translated, and preserved many written works. Monasteries played an important role in the development of Christian theology, and many became centers of learning.

Eastern Orthodox Church

Christians in the east did not accept the authority of the Pope that was claimed in the west. They instead relied on the guidance of the highest ranking bishops within the Eastern Church known as Patriarchs. In addition, there were also doctrinal disputes between the Eastern and Western Churches, including the relationship of the Holy Spirit to God the Father. These differences led to further division between the Eastern and Western Churches during the era of the Crusades.

In the year 1099, many Christians traveled from Europe to Palestine with the intention of forcefully reclaiming Palestine for Christians. The land of Palestine, including the city of Jerusalem, had been conquered by Muslim forces in the seventh century CE. This military action led to the Crusades-a series of religious wars lasting two centuries with the goal of reclaiming the holy land.

In 1204 CE, crusaders from western Europe ransacked religious sites in the city of Constantinople which were sacred to Christians in the east. This angered the Eastern Church, creating additional tensions between the Eastern and Western Christian organizations. Both churches excommunicated one another. Excommunication is the act of being denied religious sacraments, which equates to being denied eternal salvation. The resulting separation between the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church continues to this day.

For the next 1,000 years the Eastern Orthodox Church worked toward a harmonious power-sharing relationship between the Byzantine Emperor and the Patriarchs of the Church. This form of Christianity spread primarily to Russia and the Balkans. In 1453 CE, Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks and the eastern half of the Roman Empire became ruled by the Islamic Ottoman Empire.

From the Protestant Reformation to the Present: 1534 CE to present

In 1517 CE, a German monk named Martin Luther (1483-1546 CE) nailed a list of 95 debate topics and questions to the door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany, known as Luther’s 95 Theses. Among them, Luther debated the buying and selling of indulgences, meaning the extra-sacramental remission of temporal punishment due to sin that has been forgiven, and other teachings of the Church. For some time, people had been calling for change, arguing that the system of paying for indulgences had corrupted the Church. Others, such as Erasmus (1466-1536 CE) argued that Christians could read the Bible themselves and live Christian lives without the intercession of Roman Catholic priests. By challenging Church authorities to discuss these issues openly, Luther encouraged Germans to question Roman Catholic dogma. Church authorities asked Luther to retract his ideas and return to orthodox positions, but he refused. The theological positions of Luther will be discussed in the section on Doctrine in this chapter.

In 1519 Luther was excommunicated from the Catholic Church for heresy. It was quite serious, for an excommunicated person would not have access to the sacraments necessary for salvation and faced hell in the afterlife. Practically speaking, since it was considered a crime against the Roman Catholic Church, a heretic could be prosecuted and put to death. The teachings of Luther had become so popular in Germany and Scandinavia, however, that he was protected by political leaders. Violence between supporters of Lutheranism on one side and supporters of the Roman Catholic Church broke out. By 1555 CE, when the fighting ended, northern Germany and Scandinavia were predominantly Lutheran. Conflict between Catholic and Protestant groups continued in various regions through the 19th century CE.

Another important movement during the Protestant Reformation was Calvinism. The founder of Calvinism was a French lawyer named John Calvin. He moved to Geneva Switzerland where he produced his own theological works and became a church leader. His theology included predestination, the view that since God is omnipotent (all-powerful) and omniscient (all-knowing), He knows beforehand who will be saved and go to heaven, and who will be condemned to hell. Still, it was important that everybody go to church and avoid sin.

In 1553, Calvin attracted notice when he charged Michael Servetus for heresy. Servetus, a fugitive who was wanted by both Catholics and Protestants, rejected infant baptism, and denied the doctrine of the Trinity on the grounds that it was not found in the Bible. Since he would not recant, Calvin had him burned at the stake for heresy. Violence on both sides of the Reformation did not subside until the Peace of Westphalia that ended the war between the Protestants and the Catholics in 1648 CE.

Christianity Spreads throughout the World: The Age of Exploration

As Western European cultures spread throughout the world during the Age of Exploration (c. 1450–1600 CE), so too did their versions of Christianity. Much of Christian expansion outside of Europe was established by explorers. But many Christians, especially Protestant groups, came to the Americas in search of religious freedom. European colonizers sought to convert the people in regions they conquered, but missionaries were also influenced by the indigenous religions they encountered. This process of change and adaptation within Christianity continues today and accounts for much of the success and diversity of Christianity throughout the world.

As Christianity spread, it adapted and changed in response to many different currents of thought and social contexts. The philosophical movement in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries CE known as the Enlightenment challenged many basic assumptions of Christianity. The emphasis on rationality as opposed to religious orthodoxy led to different adaptations within Christianity. One response was deism, which emphasized the rational elements of Christianity while downplaying its more supernatural and inexplicable elements. Another movement was fundamentalism, which sought to return to more fundamental versions of Christian practice that were undermined by advancements in science and technology fostered by Enlightenment. [See New Religious Movements chapter for more information about Christianity in America.]