73 Overview of Native American History

Timeline of Native American History

- 1492 CE – Christopher Columbus lands on a Caribbean Island after three months of traveling through the Atlantic Ocean. Believing at first that he had reached Asia, he describes the natives he meets as “Indians,” meaning people from India.

- 1513 CE – Spanish explorers led by Vasco Nuñez de Balboa locate the Pacific Ocean by route of Panama.

- 1519 CE – Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés make contact with the Aztecs and other Nahuatl-speaking peoples in Mexico.

- 1533 CE – Spanish conquistadors led by Francisco Pizarro sack the city of Cuzco, the most prestigious Incan city in Peru.

- 1539 CE – Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto lands in Florida, but leads a failed expedition.

- 1622 CE – the Powhatan Confederacy nearly wipes out the English colony Jamestown (in modern-day Virginia).

- 1680 CE – the Indigenous Pueblo of New Mexico overthrow the Spanish government in New Mexico, known as the Pueblo Revolt of 1680

- 1754 CE – The French and Indian War begins, pitting these two groups against English settlements in North America.

- 1756 CE – The Seven Years’ War between the British and the French begins, with Native American alliances aiding the French.

- 1763 CE – Ottawa Chief Pontiac leads Native American forces into battle against the British in Detroit.

- 1804 CE – Native American Sacagawea, while 6 months pregnant, meets explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark during their exploration of uncharted territory from the Louisiana Purchase. The explorers realize her value as a translator.

- 1812 CE – President James Madison signs a declaration of war against Britain, beginning the war between U.S. forces and the British, French and Native Americans over independence and territory expansion.

- 1830 CE – President Andrew Jackson signs the Indian Removal Act, which gives plots of land west of the Mississippi River to Native American tribes in exchange for land that is taken from them.

- 1851 CE – Congress passes the Indian Appropriations Act, creating the Indian reservation system. Native Americans aren’t allowed to leave their reservations without permission.

- 1860 CE – A group of Apache Native Americans attack and kidnap a white American, resulting in the U.S. military falsely accusing the Native American leader of the Chiricahua Apache tribe, Cochise. Cochise and the Apache increase raids on white Americans for a decade afterwards.

- 1876 CE – In the Battle of Little Bighorn, also known as “Custer’s Last Stand,” Lieutenant Colonel George Custer’s troops fight Lakota Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull, along Little Bighorn River. Custer and his troops are defeated and killed, increasing tensions between Native Americans and Anglo Americans.

- 1879 CE – The first students attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, the country’s first off-reservation boarding school. The school, created by Civil War veteran Richard Henry Pratt, is designed to assimilate Native American students.

- 1890 CE – U.S. Armed Forces surround Ghost Dancers led by Chief Big Foot near Wounded Knee Creek in South Dakota, demanding the surrender of their weapons. An estimated 150 Native Americans are killed in the Wounded Knee Massacre, along with 25 men with the U.S. cavalry.

- 1907 CE – Charles Curtis becomes the first Native American U.S. Senator.

- 1918 CE – Choctaw soldiers use their native language to transmit secret messages for U.S. troops during World War I’s Meuse-Argonne Offensive on the Western Front. The Choctaw Telephone Squad provide Allied forces a critical edge over the Germans.

- 1942 CE – Members of the Navajo Nation develop a code to transmit messages and radio messages for the U.S. armed forces during World War II. Eventually hundreds of code talkers from multiple Native American tribes serve in the U.S. Marines during the war.

- 1969 CE – A group of San Francisco Bay-area Native Americans, calling themselves “Indians of All Tribes,” journey to Alcatraz Island, declaring their intention to use the island for an Indian school, cultural center and museum. Referencing Europeans’ colonization of North America, they claim Alcatraz is theirs “by right of discovery.” On June 11, 1971 armed federal marshals descend on the island and remove the last of its Indian residents.

- 1975 CE – Congress passes the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which reverses the termination policy of previous decades when American Indian tribes were disbanded, their land sold and “relocations” forced Indians off reservations and into urban centers. The 1975 act provides recognition and funds to Indian tribes.

- 1980 CE – President Jimmy Carter signs the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act. The act grants Indian tribes, including the Passamaquoddy, Maliseet and Penobscot, $81.5 million for land taken from them more than 150 years ago.

- 1990 CE – President George H.W. Bush signs the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA into law. The act requires federal agencies and museums that receive federal funds to repatriate Native American cultural items to their respective peoples.

- 2020 CE – The Washington National Football League franchise announces it is dropping its name, the “Redskins,” as well as its Indian head logo. The move is in response to decades of criticism that they are offensive to Native Americans. The team is eventually renamed the Commanders.

- 2021 CE – Representative Deb Haaland of New Mexico is confirmed as secretary of the Interior, making her the first Native American to lead a cabinet agency.

Early Human Beings

Indeed, Native Americans had populated much of North and South America by the time Columbus and his crew disembarked from three ships: the Niña the Pinta, and the Santa María. And while archeological evidence at sites like Monte Verde (modern-day Chile) suggests that certain peoples arrived from Asia in boats, most early humans were thought to have arrived thousands of years ago on foot. How can such a thing be explained by modern-day scholars?

Many scholars endorse the “Out of Africa” hypothesis, which maintains that humans (homo sapiens) originated in Africa about 100,000 years ago. Of course these homo sapiens had their own ancestors, so there are various hominid species like homo habilis and homo erectus. For sake of brevity, this chapter will address the importance of humans (specifically homo sapiens) leaving Africa, travelling to Asia, and then populating North and South America. Over time, these early humans migrated “out of Africa” and into Asia and Europe. Add more time to the mix, and it is believed humans in eastern Asia migrated to the Americas on foot in pursuit of big game. It is thought the last Ice Age created a land bridge (made of ice) from the Bering Strait to modern-day Alaska, offering mastodons, caribou, and the first Native Americans access to the Americas. The following section outlines this theory further by using archeology, anthropology, and history to explain how Native Americans came to be.

The Last Ice Age

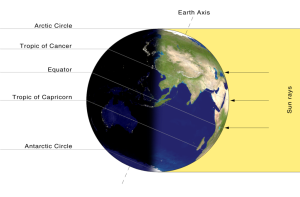

When referring to Earth’s axis, a few degrees can drastically alter the climate. The moon’s pull on our planet’s oceans causes the tides, and the combination of tidal forces exerted by the sun and moon on our rotating planet is known as axial precession, the phenomenon responsible for the last Ice Age. The last Ice Age ended approximately twenty-five thousand years ago. The change in the Earth’s axis as these forces took effect altered the amount of sunlight that hit the planet (see photo below). At times, our planet received less direct light from the sun, causing massive increases in ice as it grew colder. The increased amount of ice during the last Ice Age meant that ocean waters receded around the Bering Strait, thereby providing a land route to Alaska for early humans in pursuit of big game. These early peoples are the ancestors of Native Americans today.

The illustration above shows how the sun warms our planet with its rays hitting the tropics and equator hardest. If Earth’s axial tilt changes, so does the weather. The tilt in the axis causes the seasons, not the Earth’s position to the sun in its yearly orbit. In fact, our planet is closest to the sun every year in early January. If it were truly our planet’s position relative to the sun which caused the seasons, January would be summer for everyone, not just for those in the Southern Hemisphere. This fact shows that angles matter a great deal when referring to the axis of our planet. The irregularities in Earth’s axial tilt have caused multiple Ice Ages. However, it is the last Ice Age that concerns us here because it facilitated the populating of the Americas with their very first inhabitants.

The First Native Americans

About thirteen-thousand years ago, hunter-gatherer groups emanating from northeastern Asia populated the Americas in pursuit of animals like mastodon and caribou. At this time, the Bering Strait was hundreds of miles wide and remained covered in solid ice. The causes for such emigrations are unknown, so without additional evidence we will assume that a shortage of resources propelled certain groups across the strait into Alaska. Perhaps a shortage of resources caused fights to break out between different nomadic groups. The spears and weapons that killed big animals also harmed humans. These early nomadic peoples’ instinctual drive to obtain scarce resources might help to explain the treks known to have populated the Americas with the first Native American peoples.

Early human remains at Monte Verde in Chile have generated considerable debate; however, modern scholars now accept that some fisher peoples moved along the coastline of North and South America before the land bridge existed. Cave art from the region shows evidence of animal domestication. See, David Metzer’s First Peoples in a New World (2009). For this course, the takeaway should be that global changes in the weather gave humans access to the Americas.

Although a slow process, the last Ice Age did eventually come to an end. When this occurred, the Old World became separated from the New World. Axial precession had tilted Earth and warmed the planet, causing much more ice to transform into liquid water. This surge of new waters covered the land bridge, melting it as the entire sea level rose.

Of course, this effect impacted the entire world, not just the Bering Strait. More water meant more plants, so early humans around the globe experimented with eating a variety of new fruits, roots, seeds, and stalks. In many of these hunter-gatherer societies, men spent most of their time hunting, while women spent much of their time gathering. It proved beneficial for these early humans to observe all they could about the natural world. They listened to one another to learn about the natural environment, noting which plants grew from which seeds. After some time, they sowed the seeds of their favorite plants and harvested them in the following years when the hunt for animals drew them back to their old stomping grounds. Women would tell men about the bushes that grew the most berries, using their seeds to feed the next generation of early humans. Men would occasionally be successful in their hunt of game, adding valuable protein to their diet. These early humans became part-time farmers almost everywhere around the world but activities like hunting and fishing continued to yield the protein so vital for survival. Prayers and supplications were uttered before beginning a hunt. Hunters might try to appease the spirit world by uttering sacred words.

The Hunt and Cave Art

Certain Netsilik Eskimo peoples of modern-day Canada uttered the following prayer to bring good fortune in a caribou hunt:

Great swan, great swan, Great caribou bull, great caribou bull, The land that lies before me here, Let it alone yield abundant meat…Come here, come here,Your bones you must move out and in,To me you must give yourself!

Cited from Asen Balikci, The Netsilik Eskimo (Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press Inc., 1989), 217–18.

Originally recorded in 1931, the above supplication connects hunters to the land and its animal inhabitants. For many Native peoples today, cosmologically, a hunted animal provides its body as an offering to the successful huntsman. Archeological examples such as the Cave of Hands shows us that some of the first Native Americans soon took to carving and painting animals on cave walls, animal hides, or scraps of bones as a way to influence their success in hunting and, subsequently, increase their chances of survival.

Cave of Hands (Cueva de las Manos)

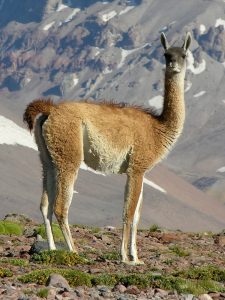

The Cave of Hands in the Argentine town of Perito Moreno is a large complex of rock art sites created in numerous waves between 7,300 BCE and 700 CE. These early Native Americans hunted the guanaco—a quadruped related to the llama.

The remains of the guanaco can be found throughout the complex. Handprints can also be seen throughout the complex. The handprints shown above were made of soil rich in iron oxide, charcoal, and bones, all of which was mixed together with animal fats or saliva. The hand stencils were made by blowing pigment through a hollow bone or some other tube. The Cave of Hands seems to show the importance early Native Americans placed on the hunt and animals like the guanaco.

When possible, early humans made art to better their chances of survival. Unfortunately, we do not know much detail about the rituals performed or words spoken among these peoples. Still, early humans in Europe offer many points of comparison to the aforementioned Cave of Hands in Argentina. In Spain, a cave complex known as Altamira was discovered in 1868. Several millennia ago, a landslide is thought to have sealed the cave, thereby preserving human-made paintings that would have inevitably eroded over time. Once inside the cave, visitors can see detailed pictures of wild animals, including deer, buffalo, and horses.

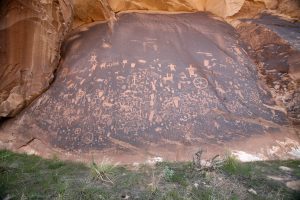

Some animals such as the red deer (far left) are life-sized. The buffalo (above) is drawn in charcoal and is the most frequently painted animal in the complex. These pre-historic monochrome animal paintings were created between 22,000 to 13,000 years ago. While the motives that impelled these early humans to create their art on rock surfaces remains mysterious, many scholars believe these images served ceremonial and ritual purposes. The hunt so closely related to survival it seems logical that it can be seen in caves around the world. Early humans wanted to increase their chances of survival any way they could. Perhaps these early humans drew the object of their desire, e.g. the guanaco, deer, buffalo, etc., with the hope of altering their reality. Another example discussed below takes us to Utah in the United States.

In the close-up, you can see a humanoid figure hunting a deer-like animal with a projectile. Is this human-like figure mounting another animal? Perhaps, the hunter is merely behind this horse-like animal. Questions always remain when you delve into such topics. You will see human feet placed next to animals. Perhaps, these early hunters wanted to run more quickly so they could more easily kill their prey. Perhaps, these early hunters carved feet into the rocks to symbolize the trampling or stomping of prey. Without further contextual evidence like pottery, it remains difficult to conclude anything with certainty.

However, it is very tempting to suggest that the above examples of cave art show how early humans attempted to influence their prowess as hunters. At a more general level these petroglyphs show concern for survival, hence the need to draw or paint what one wishes to control. Maybe, just maybe, these early humans chanted something similar to the twentieth-century Netsilik Eskimo prayer noted above. Assuming this to be the case, we may suggest human beings’ first indelible inscriptions stemmed from a desire to control animals so as to better their chances for survival in a terrestrial world. It seems likely that early humans invoked some aspect of nature, like asking for good weather, or perhaps uttered a solemn prayer to an unknown deity while making these images. The following example takes us to South America, where Native Americas left an enduring impression of a massive hummingbird upon the landscape.

Nazca Lines

Created between 500 BCE and 500 CE in southern Peru, the Nazca Lines converge on its horizon during the Southern Hemisphere’s winter solstice, suggesting they have calendrical functions not yet fully understood. Scholars know more about how the lines were produced than their original meaning for early Native Americans. In southern Peru, the topsoil is so thin that early Native Americans easily brushed away dirt to reveal the chalk underneath. The chalk helped to create lines, which these Indigenous peoples used to draw human and animal figures. However, the shape of these figures cannot be appreciated from the ground level. This means that large groups of Native peoples came together to work in coordination to construct these Nazca Lines. Very interesting indeed!

Nazca Lines are geoglyphs carved into the Peruvian desert. The famous Nazca hummingbird is shown here. The hummingbird is approximately 320 feet long and 216 feet wide. In total, there are hundreds of geometric figures and dozens of depictions of plants and animals, all of which comprise the Nazca Lines.

Nazca Lines are believed to have had ritual and astronomical purposes. Scholars suppose that sites like the Nazca Lines demonstrate evidence of shared labor and collective action as they remain too complex to have been created by a single individual. From the lines, scholars surmise that peoples came together to produce culturally meaningful glyphs.

Intriguingly, the Nazca Lines’ intended design only becomes apparent from an elevated position. Perhaps this fact means a scaffold or similar structure was used by a team of workers who shuffled topsoil to reveal the chalk just underneath. This provides us with a logical explanation of creation, i.e. collective labor by Native peoples in the distant past. While this answer helps us to understand the “how” of the Nazca Lines, many other questions remain. What did the above hummingbird actually mean for these predecessors of the Inca? Unfortunately, the exact meaning surrounding the Nazca Lines will remain occluded for some time, maybe forever. Still, they show that Native peoples in South America paid close attention to their natural environment and came together to leave their mark on the landscape.

Symbolism and Collective Action

Thus far, we have seen that early Indigenous peoples in the Americas left their mark on the landscape in caves, on cliffs, and on the ground. Some of the examples cited above might have been created by individuals acting alone. However, other examples (e.g. the Nazca Lines of Peru and the pyramids of Mexico) clearly demonstrate collective action. How did these societies understand their world and how did they make sense of it all? Animals figured prominently in early human societies as noted in the cave art from pre-historic times in both Europe and the Americas. The hand stencils on caves at Altamira (Spain) and Perito Moreno (Argentina) show that early humans touched rock faces and made indelible marks to depict hunting and other types of activities, presumably, sacred to them.

In our attempt to understand early humans, there is no need to impose a false world upon them, meaning there is no need to presume they separated “church and state” in any way like the United States does in the twenty-first century. To draw, paint, and sketch upon the landscape was to interact with the environment so that humans could increase their chances of survival, and drawing, painting, and carving left permanent marks of humans’ existence. It seems likely that early Native Americans left petroglyphs and made carvings to bring about good fortune in the temporal world, meaning the here and now. These markings might appease the gods because nature was the manifestation of their labor.

Symbolism and Collective Action

Thus far, we have seen that early Indigenous peoples in the Americas left their mark on the landscape in caves, on cliffs, and on the ground. Some of the examples cited above might have been created by individuals acting alone. However, other examples (e.g. the Nazca Lines of Peru and the pyramids of Mexico) clearly demonstrate collective action. How did these societies understand their world and how did they make sense of it all? Animals figured prominently in early human societies as noted in the cave art from pre-historic times in both Europe and the Americas. The hand stencils on caves at Altamira (Spain) and Perito Moreno (Argentina) show that early humans touched rock faces and made indelible marks to depict hunting and other types of activities, presumably, sacred to them.

In our attempt to understand early humans, there is no need to impose a false world upon them, meaning there is no need to presume they separated “church and state” in any way like the United States does in the twenty-first century. To draw, paint, and sketch upon the landscape was to interact with the environment so that humans could increase their chances of survival, and drawing, painting, and carving left permanent marks of humans’ existence. It seems likely that early Native Americans left petroglyphs and made carvings to bring about good fortune in the temporal world, meaning the here and now. These markings might appease the gods because nature was the manifestation of their labor.

The Aztecs of Central Mexico

Readers should note the huge gaps in time that take place from the preceding paragraphs to those below. The following section details aspects of the theology of Native Americans known as the Aztecs. The Aztec peoples did not come into being until c. 1325 CE, after the founding of the city of Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City). In order to provide acute detail of religious beliefs, Native peoples had to develop advanced forms of writing. Mesoamerican peoples developed their writing independently, meaning scholars do not think they learned to write from the Old World, i.e. via China or northeast Asia. Nevertheless, various codices exist for early Native peoples such as the Aztec, Maya, Mixtec, Olmec, and Zapotec scripts. These peoples used various glyphs, meaning drawn pictures, to describe food, to establish dynasties for Native rulers, and to name their gods. With an elaborate theology in place, these Indigenous peoples went about building the first pyramid structures, giving thanks to the heavens.

Agriculture in Mesoamerica

When larger groups of individuals came together, they built monumental works of art to bring about good fortune for the well-being of the community. The pyramid shown above is known as the Pyramid of the Sun (Pirámide del Sol in Spanish), itself situated within a vast archaeological complex known as Teotihuacán, northeast of modern-day Mexico City. Teotihuacán is a Nahuatl term that means “place of the gods.” Nahuatl is the language of the modern-day Nahua peoples in Mexico. It was also the language of the Aztecs, including the famous Emperor Montezuma. But, the city of Teotihuacán is much older than the Aztecs. The Aztecs drew much of their identity as a people from Teotihuacán and its former inhabitants, the Olmec peoples. In fact, Teotihuacán was one of the largest cities in the ancient world, thought to have supported between 125,000 to 200,000 people.

With these numbers in mind, one can see that the Pyramid of the Sun was certainly built by humans such as the Olmec—predecessors to the Aztecs. The differences between cave art and monumental structures are many, so we will focus on the repercussions of the technology of writing and its effect on the organization of labor. Ramps, ropes, and pulleys were the tools of manual laborers while architects and scribes used quills and paper to enact royal decrees and build monuments to the gods. The Native Maya and Aztec peoples made paper from the bark of a fig tree. In Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, the two-syllable word amatl (ah-maht) means paper. Such technology occurred independently in many societies around the world. Writing was used to keep records, tax vassals, and commune with the gods. In the ancient world, all of this could be achieved simultaneously, no need to separate church and state. Remember, people of a different culture and time do not have to think about things the way we do.

Scholars believe Teotihuacan’s population was supported by tracts of drained fields known as chinampas, derived from the Nahuatl chinamitl, meaning a fenced area or enclosure made from reeds or sugar cane. The surrounding agricultural areas were overseen by a central authority who controlled the means of production. Scholars are confident this was the case because the chinampa system (see below), though highly productive, required intimate knowledge of botany and necessitated knowledge of carpentry. We know that Teotihuacan thrived as a populous city around 300 CE, but much about the structure of its society and its religious practices remains unknown. Still, Teotihuacan’s pattern of gridded streets and apartment compounds shows that many people came together to create colossal stone buildings and pyramids to worship their gods.

A workforce was sustained by an ingenious method known as the chinampas. Here, earth was held together, then laid atop a platform that floated on fresh water. Slits in the platform allowed plant roots to draw water from lakes and streams.

Writing and urbanization remained closely tied, meaning that the technology of writing usually originated in cities or towns. Such technology then created a new class in urban areas. Throughout history, priests, scribes, and kings utilized writing as a technology of power. Many people believe heaven’s secrets can be recorded in writing, even today! We see this in religious texts such as the Bible or the Quran, and past societies were no different. Recording sacred prayers and key events helped to interpret the universe, appease the gods, and solidify the community living in the terrestrial realm. Avoiding catastrophe was paramount to survival. In Mesoamerica, as in the Old World, a literate priestly class developed in urban areas, themselves sustained by agriculture. More people meant larger projects to worship the gods, hence complexes like Teotihuacan.