7 Cosmology

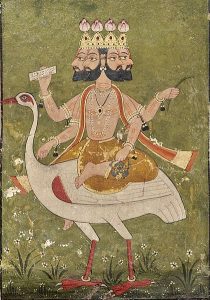

Hinduism views time and creation as cyclical. The cycles of creation, maintenance, and destruction are repeated as a natural process aided by the gods. One cycle from creation to destruction is called a kalpa and equals one day in the life of Brahma, or 4.32 billion earth years. The term kalpa appears in Buddhist texts and also in the Mahabharata epic tale. The Hindus imagined tremendous periods of time in their calculations. Brahma is sometimes depicted riding Hamsa, the swan. The name Hamsa means pure. Brahma uses Hamsa to chant the Vedas. The image of Brahma below shows him with four heads, to represent the four cardinal directions of north, south, east, and west. Brahma holds the scriptures of the Vedas; a mala (rosary) whose beads represent time; and ritual implements to feed the sacrificial fire and to represent water, the basis of life.

Purusha, the Primordial Sacrifice

The Rig Veda described creation as a primordial sacrifice of Purusha, seen as pure spirit. The sacrifice of this spiritual body created the world and became the source of different social classes. In the Rig Veda, the world-creating sacrifice was seen as a single event that occurred in the past. Later interpretations saw it as cyclical and tied to the state of humanity.

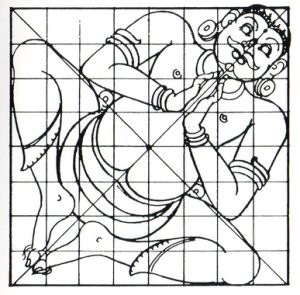

Purusha is sometimes depicted as a diagram intersected by lines as if it were a map of the cosmos. Notice the similarity in posture between this image of Purusha and the Indus Valley Seal found at Harappa. This shows how the posture of meditation is deeply embedded in the culture of India.

Hindu cosmology emphasized the role of the sacrifice in both creating and maintaining the world. Humans support both the gods and the universe by performing sacrifice properly. The Upanishads, the last work of the Vedas, introduced the idea of atman and Brahman, arguing that although humans usually view the world of the senses as real, in fact it is an illusion. Sensory input does not reveal the fundamental reality.

Only the atman of the individual is unchanging in Hinduism. The Upanishads taught that its unchanging essence is the same as the reality of the universe, Brahman. In order to understand this, a person must discipline the body and mind through study and yogic practice. All material reality flows from Brahman and all creation is Brahman. The illusion of independent individuality is often compared to seeing a rope on the ground in the dark and mistaking it for a snake. Once you see that it is a rope, you become free from the illusion of a dangerous snake.

As Hinduism develops, sacrifice becomes less important than the mental, moral and physical control of the three types of yoga: knowledge or jnana, action or karma and devotion or bhakti. Through yoga a person works toward transforming ignorance into knowledge.

Karma

In Brahmanical religion, the word karma refers to action within the ritual. These ritual actions are thought to have the power to effect the universe by nourishing the gods and sustaining order. The knowledge of the hymns and how to do the ritual was considered to be sacred as it was passed down from wise people called rishi who had heard the hymns through great spiritual power. This knowledge was called sruti, that which is heard. It is not created by humans, but is received from the universe. Sruti is contrasted with literature that is remembered or smrti.

The sacrifice performed by trained specialists was seen as a way to shape the world through their control of the physical elements of fire and the ritual drink called soma. Fire and Soma were also gods as well as being the physical substance used in the ritual. The human performance of a ritual was seen as something that could compel the gods to act. In this way, the power of the individual gods was secondary to the unitary principle of the world, Brahman. In Hinduism, ultimate reality is not the multitude of the gods, but their underlying unity.

The ritual, as a karmic act, is also related to the idea of the self. By performing the ritual, the priest creates a being that represents the sacrifice, Prajapati. Through the action of the sacrifice, Prajapati dies, but he is born again with the next ritual. The cycle of creation and destruction in the performance of ritual led to the concept of cycles of death and rebirth called samsara.

As we have seen, The relationship between cosmic sacrifice and humanity is also expressed in the figure of Purusha. In the early Vedas the sacrifice of the great being, Purusha, created both the universe and the classes of human society: priests, rulers, workers, and servants out of parts of his own body. This concept of the sacrifice of a great being as a creative act that established the world as we know it is powerful. It combines the sacred ritual of sacrifice with the facts of ordinary life: what class you were born into and the duties that belong to that class are part of the cosmic order.

Cosmic order in religions of India is based on two main principles. First, time is cyclical, without beginning or end. The world is created, maintained, and finally destroyed to allow for new creation. These cycles of creation, continuity, and destruction take place over enormous periods of time. Many of the gods that we learn about in this chapter are associated with one part of this cyclical process but none of them control all three phases of the cycle. Second, although the gods are powerful, they are also subject to the cycles of the universe and karma. The literature of India from the Vedas to the Puranas illustrate this flexible attitude toward divinity.