57 Doctrines of Christianity

Who was Jesus?

Jewish identity of Jesus: fulfilling the promise of a Messiah

The “Historical Overview” in this chapter made it clear that Jesus was born to Jewish parents and grew up within the Jewish community. He received spiritual purification in a Jewish rite of baptism by John the Baptist and began his ministry. People who followed his teachings saw Jesus as a possible messiah, which meant a person who would be anointed by God to establish a Jewish kingdom. Notice that this conception of a messiah does not include any sense of a person being divine, but rather that a messiah is chosen by God to lead the people of Israel.

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) has passages that shaped the concept of the messiah in Jewish belief. As Christianity developed these passages were quoted as evidence that Judaism had predicted Jesus as the future messiah. The following passage from Isaiah was particularly important. As you read through the passage, think about how the life of Jesus as described in the gospels reflects these ideas:

Who has believed what we have heard? And to whom has the arm of the Lord been revealed? For he grew up before him like a young plant, and like a root out of dry ground; he had no form or majesty that we should look at him, nothing in his appearance that we should desire him.

He was despised and rejected by others; a man of suffering and acquainted with infirmity; and as one from whom others hide their faces he was despised, and we held him of no account. Surely he has borne our infirmities and carried our diseases; yet we accounted him stricken, struck down by God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions, crushed for our iniquities; upon him was the punishment that made us whole, and by his bruises we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray; we have all turned to our own way, and the Lord has laid on him the iniquity of us all. He was oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he did not open his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent, so he did not open his mouth.

By a perversion of justice he was taken away. Who could have imagined his future? For he was cut off from the land of the living, stricken for the transgression of my people. They made his grave with the wicked and his tomb with the rich, although he had done no violence, and there was no deceit in his mouth.

Yet it was the will of the Lord to crush him with pain. When you make his life an offering for sin, he shall see his offspring, and shall prolong his days; through him the will of the Lord shall prosper. Out of his anguish he shall see light; he shall find satisfaction through his knowledge. The righteous one, my servant, shall make many righteous, and he shall bear their iniquities.

Therefore I will allot him a portion with the great, and he shall divide the spoil with the strong; because he poured out himself to death, and was numbered with the transgressors; yet he bore the sin of many, and made intercession for the transgressors. (Isaiah Chapter 53, NRSV)

Christians have used this passage from Isaiah in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament) to argue that Jesus is the fulfillment of a prediction that is deeply linked to the faith of the ancient Israelites.

Jesus as God: the Nicene Creed

The purpose of the first Council of Nicaea, as it came to be called, was to develop a standard creed for Christianity. A creed is a statement of belief in a religion. Not all religions have creeds, but orthodoxy or “correct belief” was important throughout Christian history. The Council of Nicaea sought to define Christian orthodoxy, which means “right belief.” This council, by deciding what was correct belief, classified other beliefs as incorrect. The word heresy literally means “choice,” but if only one set of beliefs are orthodox, then choosing the “wrong” belief is a serious error. When a religion becomes aligned with the state, then heretical views, meaning incorrect beliefs, can be punished by the state.

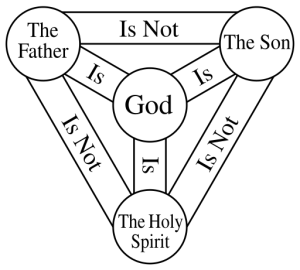

One of the interpretations of Christianity that the Council of Nicaea labeled as heresy was that of Arius of Alexandria. The writings of Arius contradicted the view that the Christian God could be expressed as a Trinity of three persons: the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit. Each of these persons is distinct from the others, but all three are God. Arius argued that as the Son of the Father, i.e. Jesus, was created by God and, therefore, had a beginning. Arius was accused of heresy for his views. In 325 CE, the Council established their own official stance concerning the Trinity in what is known as the Nicene Creed. The Nicene Creed defined the nature of Jesus and the Trinity and became a binding statement for all Christians of the Roman Empire:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father [the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God,] Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; By whom all things were made [both in heaven and on earth]; Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down and was incarnate and was made man; He suffered, and the third day he rose again and ascended into heaven; From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead; Whose kingdom shall have no end…

In 381 CE, when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, authorities revised the creed, mainly to oppose further ideas of Arius and his followers. This version is used in many Christian denominations today.

Another group that operated outside of Christianity as it was defined in the Nicene Creed were the Gnostics. They focused primarily on the mystical experience of God and knowledge (gnosis), and had a much different interpretation of the life and teachings of Jesus than mainstream Christians.

The Two Versions of the Nicene Creed

Compare these two versions of the Nicene Creed, the first from 325 CE; and the second from 381 CE when Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. What did they add to the creed? How is Jesus described in the two creeds? Notice the narrative elements in the two creeds are slightly different, with the second creed including more supernatural aspects of the birth of Jesus.

Nicene Creed from the First Council of Nicaea (325 CE)

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father [the only-begotten; that is, of the essence of the Father, God of God,] Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; By whom all things were made [both in heaven and on earth]; Who for us men, and for our salvation, came down and was incarnate and was made man; He suffered, and the third day he rose again and ascended into heaven; From thence he shall come to judge the quick and the dead; Whose kingdom shall have no end…

Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed from the First Council of Constantinople (381)

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds (æons), Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father; by whom all things were made; who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary, and was made man; he was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate, and suffered, and was buried, and the third day he rose again, according to the Scriptures, and ascended into heaven, and sitteth on the right hand of the Father; from thence he shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead. And in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceedeth from the Father, who with the Father and the Son together is worshiped and glorified, who spake by the prophets. In one holy catholic and apostolic Church; we acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; we look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come.

Medieval Catholic Theology

Many aspects of contemporary Christian theology stem from medieval Christian writings. One theological question centered on what happens after death to Christian believers? Medieval theologians theorized three main afterlife destinations: heaven, hell, and purgatory. A fourth minor afterlife destination, known as limbo, is reserved for infants who died before they had sinned. Of all the afterlife destinations, heaven is the best place a Christian could end up. Heaven is a place close to God reserved for those who lead perfectly good Christian lives. Hell is the opposite: a place far away from God reserved for those who stray from the ethical teachings of the Church. A person who ends up in hell is there for all of time with no possibility of leaving. Purgatory is the destination that awaits the majority of human beings. This is the destination for the souls of those whose sins must be worked off through penance before entering heaven. Once those souls have suffered enough for their sinful actions in life, they go to heaven.

These afterlife destinations created anxiety among medieval European Christians. After all, the majority of belivers would, it seemed, end up in purgatory, including loved ones. However, the power to alleviate the suffering of those who have died was out of the control of everyday Christians.

During this time, the Catholic Church claimed that only priests could administer the sacraments necessary for salvation. Sacraments are religious rites that are administered by the Church to Christians for their salvation such as baptism and communion. A system developed where people could pay money to the Church to expedite the stay of their loved ones in purgatory. In return for the money, the Church would communicate with God to shorten the stay of the person in purgatory. This shortening of someone’s stay in purgatory by the Church was known as an indulgence.

Medieval theologians made important contributions to Catholic theology. One of the most important medieval theologians was Thomas Aquinas (c. 1225-1274 CE), who used Greek philosophy to interpret Christian theology. Specifically, he used the ideas of the Greek philosopher Aristotle to show how Christianity was rational. He also wrote about the concept of a vital soul, which is the idea that all living things have a soul that separates them from non-living matter. For more information about “vital soul”, see the Anthropology section of this chapter.

Medieval Christianity: Sacraments

The Nicene Creed confirms Paul’s statements, saying that belief in God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit brings salvation and resurrection. Later, the Roman Catholic Church added seven sacraments, meaning the ritual obligations for this formula of salvation. The Church taught that following the sacraments ensures that people are living good Christian lives. Five sacraments would be experienced by all Catholics:

- baptism: infant initiation and symbolic purification of sin through water. Baptism may also be performed for adults in some Christian groups.

- confirmation: declaration of commitment to Christ when a child has matured, i.e. adolescence or adulthood.

- reconciliation: confession or penance of sins.

- holy communion (Eucharist): ritual “meal” with Christ.

- anointing of the sick (formerly: last rites).

Two additional sacraments are chosen by the individual:

- marriage

- ordination

The Roman Catholic Church also created a system of afterlife destinations based on the spiritual state of the person at the moment of death:

- Heaven: in rare cases, a soul is determined to be so free of sin during life that they ascend to heaven directly.

- Purgatory: a non-permanent place of suffering. A person who believes in Christ as the savior, has been baptized and received the sacraments qualifies for purgatory. The suffering itself burns off the ordinary sins (venial sins) that people committed during life. Persons who have committed mortal sins have turned away from God and the salvation offered by belief in Christ. If they do not repent before death, they will be unable to enter the state of purgatory.

- Limbo: a permanent place with a neutral quality. Reserved for, among others, unbaptized infants.

Doctrine of Original Sin

The doctrine of original sin is essentially a Christian idea. Judaism does not view human nature as inevitably tainted by sin. We have already seen how Paul of Tarsus spread the word of Christianity by arguing that we are all in need of salvation because of the disobedience of Adam and Eve. Although Paul wrote about the sin of Adam affecting later generations, Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) was the first to use the expression “original sin.” In this early interpretation, humans are born with the tendency to sin: even a baby needs to be saved from sin. Christians disagree about whether baptism removes the tendency to sin (Roman Catholics) or whether the tendency to sin continues after baptism.

Luther: Three Bases of Salvation

Luther’s emphasis on scripture was the most innovative aspect of his message. It challenged the authority of the Church hierarchy to serve as the sole interpreter of Christianity to the people. The Bible in Europe was written in Latin, a language that only scholars understood. Luther felt that laypeople should have access to the Bible and find out for themselves what it said instead of relying on the Church to interpret it for them. For this reason, he translated the Bible into German so that ordinary people could read it. His idea was to build a “priesthood of all believers” rather than relying on priests. With the technological advance of the printing press, the German-language Bible could be printed in large quantities and distributed to many people. As more people began to read the Bible and absorb the teachings of Luther, a counter Catholic movement developed.

Luther soon had a number of followers, and he developed a systematic theology based on his ideas. He argued that human beings are not saved by good works and sacraments, but rather by reading and understanding scripture, by relying on faith, and by receiving grace from God. In other words, all that matters for the salvation of human beings is that they understand and follow the teachings of the Bible, have faith in the divinity of Jesus, and cherish the grace of God.

Luther’s teaching about salvation can be summarized in these two points:

- only grace: salvation can only be through the grace of God.

- only faith: faith in Christ is the basis for one to receive the grace of God.

Related to these two bases of salvation is the idea that Christians should rely on scripture alone (sola scriptura) as their source of spiritual authority. This directly challenged Roman Catholic doctrines that emphasized the need for ordained clergy to interpret the teachings of Christ. It was Luther’s view that access to the Bible would develop faith so that there would be no need for priests to intercede for others. “Everyone a priest” was the ideal of Luther’s “only scripture.”

Many Protestant groups accepted this idea of scripture as the sole authority. In chapter nine, we will see how the Jehovah’s Witness groups take this concept so seriously that they reject the notion of the Trinity, which is not recorded in the New Testament.