16 Historical Overview of Buddhism

Life of the Buddha and Early Communities

In the sixth century the Indian subcontinent was not unified under a single leader. Instead, family and tribal groups ruled small “kingdoms.” With increasing prosperity through trade, the region developed cities, a merchant class and a money system. Prince Siddartha, the man who would become Sakyamuni Buddha, was born in an area of the Ganges plain in northern India in the sixth century BCE. This was a period of social and religious change. Rulers had concentrated economic and political power in urban areas. The rise in economic prosperity helped to support both the Brahman priestly class and the ruling nobility. Religious life was affected by social and political changes. Greater wealth made it possible for individual clan leaders to pay for expensive rituals done by the priestly class to ensure a good future rebirth.

These ancient Vedic rituals were originally performed to maintain order in the universe. The proper way to do a ritual was important knowledge that was taught from father to son in the priestly class. If done properly, the ritual had the power to command even the gods themselves. People also were concerned about the uncertainty of rebirth, being reborn lifetime after lifetime. Vedic religion was based on the belief that rituals could produce a better future birth.

Before the lifetime of the Buddha, some people began to think that the external ritual could be performed within the body through control of the senses and meditation. The Upanishads are a set of teachings that speculated about the nature of the principle of the universe (Brahman) and the individual self (atman). These scriptures introduce the idea of liberation from continual rebirth. The goal would be to escape endless rebirth by developing spiritual knowledge and control of the senses. The Upanishads suggested ways in which human beings could access the power of the universe and reach liberation through meditation techniques and self-control. These practices, however, were considered to be very demanding and required that a person withdraw from society to concentrate on meditation. Those who chose this path were called sannyasins or wanderers. They had essentially “dropped out” of social systems and class. They had no fixed home, living on donations of food and sometimes shelter. Wanderers challenged both the social and religious order. By leaving behind their social class, they left the sacred duties of their class and challenged social order. By attempting to attain ultimate knowledge of the universe, they challenged the ritual Vedic religious order.

Siddartha Gautama was born into the ruling class and would be expected to learn how to do battle as well as run an orderly state. He chose instead to become a wanderer searching for ultimate spiritual wisdom. Prince Siddartha left home at the age of 29 and practiced meditation and self-control over diet and other desires for six years. Buddhist scriptures refer to him as a bodhisattva or “Buddha to be” during this searching period of his life. After his enlightenment, he is called “the Buddha” or more precisely, Sakyamuni Buddha which means literally, “the awakened one who is the wise man of the Sakya clan”. After further meditation he decided to teach so that others could achieve the release from suffering.

Teachings: Dharma refers to the teachings of the Buddha. These teachings point to the characteristics of liberation and the method to achieve it. Sakyamuni Buddha himself claimed that he was simply the eighth Buddha in a line of previous Buddhas that stretched back over many thousands of years. From the beginning, therefore, Buddhism claimed that enlightened Buddhas had appeared in the world before. The Dharma did not depend entirely on a single person who achieved enlightenment. The Buddha gave his first sermon to some of his fellow wanderers. Most of these people became his disciples as he began over forty years of wandering to various towns and teaching. The early scriptures record his teachings to different kinds of audiences. The sutras are sermons that the Buddha gave to various groups of people; the vinaya is a set of rules and precedents that were decided by the Buddha and his early community; and the abhidharma or “further teaching” organizes these teachings into a systematic explanation.

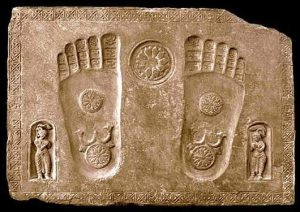

The Buddha is sometimes represented by an image of his two feet. Two wheels appear on the soles of his feet: a sign of high kingly birth. The wheel is used in Buddhism to represent the teaching which spreads through the world like a great wheel. Since the Buddha traveled on foot throughout northern India, the footprint also represents his forty years of teaching.

After his death, the Buddha’s followers organized a council to recite his teachings and memorize them. Ananda, one of the Buddha’s leading disciples recited “what the Buddha said”. These early scriptures all begin with the words, “Thus have I heard.” The person speaking is Ananda. He recites what he heard the Buddha say at a particular place and time to a particular audience. It may seem incredible that people could memorize what the Buddha had said, but in the culture of ancient India where people were trained to memorize long Vedic scriptures without error, this was quite possible.

Sakyamuni Buddha founded an order of ordained men and women. He also had lay followers, householders who helped to support the monks and nuns by offerings of food, cloth for robes, and shelter. The followers of the Buddha are called the sangha. Settled communities of ordained men and women formed in towns and at pilgrimage sites. The Buddha, his teachings, and the community of practitioners are called the three treasures. Taking refuge in or relying on the three treasures is seen as the first step to becoming a Buddhist.

The Spread of Buddhism

Buddhism first became more widespread in India under the reign of King Ashoka (265-238 BCE). King Ashoka had inherited the vast empire of Magadha, but retained this large area through various conquests. After gaining control of nearly the entire subcontinent of India, King Ashoka began to think about how to unite the various tribes and bring peace to the land. He became a convert to the Buddha’s teachings and promoted them throughout his kingdom, even sending missions to other countries. He first sought to provide his subjects with the basic necessities of life and established public works such as wells and hospitals and schools so that the people would then be able to study the teachings of the Buddha.

King Ashoka also constructed a number of stupas or Buddhist shrines throughout the land. A stupa is a repository for relics of the Buddha: this can include ashes of the Buddha’s body, but also scriptures of his teachings. Stupas became major centers of pilgrimage where visitors could tour the grounds and learn about Buddhism by looking at the carvings on the outside of the stupa. The Sanchi Stupa is a good example of how the teachings of Buddhism were illustrated. Four great stone gates surround the rounded stupa. On each gate are carved scenes from the life of the Buddha and scenes of people worshiping at the shrine. Visitors can climb the stairs that lead to a walkway around the rounded shape of the stupa. Walking around the stupa is considered to be one way to gain spiritual merit.

Buddhism beyond India

Another factor in the spread of Buddhism that had an enormous impact on northern and eastern Asia was the development of trade routes that connected regions as far west as the Arabian peninsula with China in the far east. Early Buddhist scriptures refer to two merchants whom the Buddha met shortly after his enlightenment, so scholars believe that these trade routes were established by at least the sixth century BCE. The routes, dubbed the “Silk Road” by a nineteenth century German scholar, bypassed both the Himalayas in northern India and the great Taklamakan desert in Central Asia. Typically, traders went back and forth on one portion of an entire trade route, trading in major centers only. But the goods, which also included Buddhist scriptures, would make the entire journey, passed from one trader to the next. Eventually Buddhist monks made the complete journey from India to China.

This system of trade routes and the increasing tendency of scriptures to be written down in manuscript form meant that the Buddhist teaching spread far beyond its origin in India. The main impact of the trade routes for the spread of Buddhism was approximately 100 BCE to 100 CE. In this period the prevalence of Buddhism in Central Asia and an active trade with China meant that both Buddhists and Buddhist scriptures arrived in China in the first century, in approximately 57 CE.

As Buddhism spread to countries outside of India, it was necessary to translate and record the scriptures in writing. Initially scriptures were recorded in two different written languages: Pali and Sanskrit, but some were written Central Asian languages as well. By 300 CE the Chinese government had established translation bureaus that translated the scriptures from the many languages in which they were written into Chinese. As Buddhism has spread, these scriptures have been translated first into Chinese, Japanese, and Tibetan. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries much of this literature was translated into English, French, and German. The Chinese played a pivotal role in preserving the vast majority of Buddhist scriptures and thought through their meticulous translation bureaus and classification system of Buddhist writings.

Buddhism became part of a larger Chinese sphere of influence which extended to Korea and Japan. It was natural for Korea, a peninsula on the East Asian mainland, to adopt aspects of Chinese culture quickly. Japan, an island nation across a treacherous ocean strait adopted Buddhism somewhat later, in the sixth century CE, mainly through people who had emigrated from the Korean mainland to escape unsettled conditions. By the eighth century Japan too was building Buddhist temples that rivaled the Chinese, and had adopted both the Buddhist material culture and its teachings.

In the eighth century, Emperor Shōmu of Japan promoted the building of a massive temple complex called Tōdaiji that was as ambitious an architectural project as the great temples in China. In this image you can see the grand scale of the temple and its surroundings. Todaiji represents both Buddhism and the continental culture of China in the early stages of Buddhism in Japan. At this point in history, few people could read but the imported material culture of Buddhism from China had a great impact.

Buddhism comes to the West

How did Buddhism come to the West? In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, European explorers and their missionaries to Asia were primarily concerned with spreading Christianity and subduing the indigenous populations. The Portuguese in Sri Lanka violently suppressed Buddhists during the sixteenth century. The situation was somewhat better in China, Japan, and Tibet where the Jesuits, following the suggestions of their leader, Francis Xavier, worked to understand Buddhist thought in order to be able to convert the Chinese to Christianity.

In many ways, these encounters between European missionaries and East Asian cultures, including Buddhism, Daoism, Shinto, and Confucianism showed the Europeans that it was possible to have a civilized society that did not depend on European values and beliefs. This was the beginning of an awareness of different cultures that ultimately challenged European assumptions about religion.

By the nineteenth century, both Europe and the U.S. were trading heavily with East Asia, and there was considerable interest in Asian cultures as well. In 1893 delegates from non-Christian religious groups in Asia were invited to attend the “World Parliament of Religions” as part of the Colombian Exposition in Chicago. Among the delegates were Buddhist representatives from China, Southeast Asia, and Japan. One of the lasting effects of this event was an increased interest in Buddhism as well as other Asian religions. The World Parliament of Religions helped open the door to acceptance of Buddhism and Asian religions in America.

Reinterpreting the teachings of the Buddha: 100 BCE to present

Mahāyāna Buddhism

New scriptures began to appear about 300 years after the Buddha lived. Starting in 100 BCE written scriptures gave new interpretations of what the Buddha taught. Mahāyāna or “great vehicle.” scriptures suggested new perspectives such as the eternal life of the Buddha, the manifestation of the Dharma in human form, and the potential for anyone to become a Buddha. These ideas shifted the focus of practice and belief.These scriptures could not be literally “what the Buddha said”. The texts themselves claimed to be what the Buddha really meant. The process of developing new ideas about the nature of the Buddha and his enlightenment, and the means to attain that awakening is a common pattern in religions of the world. The original insight of a founder is developed and expanded by later generations. In Buddhism, this process is explained as a natural outgrowth of putting the teachings of the Buddha into practice.

Mahāyāna scriptures, earlier Buddhist scriptures, and monastic rules all came into China at the same time, carried by merchants and a few hardy monks willing to travel the dangerous route across the desert. The Chinese set up translation bureaus and managed to translate most of the texts by the mid 400s CE. They saw that there were many different kinds of texts and they ranked them according to which ideas seemed simple and which seemed most advanced. They also assumed that the teachings described in the Mahāyāna scriptures should be put into practice. The translation work the Chinese did preserved Buddhist teachings long after the great Indian monasteries and centers of Buddhist learning were destroyed by invaders during the 1200s.

Vajrayāna Buddhism

Vajrayāna means the “way of the thunderbolt.” This form of Buddhist teaching developed in India in the seventh century CE. At the time, tantra had become a powerful idea in Indian religions. Tantras are secret methods of attaining liberation that claim to be based in ancient texts. The idea is that the physical world is infused with divine energy. A tantric practitioner tries to harness this energy to break through to liberation. In itself, Tantra is not specifically Buddhist, but was a feature of Indian religions at the time, including Hinduism.

In Buddhism, tantric ideas combined with Mahāyāna Buddhism to produce a new form of Buddhist practice: Vajrayāna. The practitioner learns to access the power of divine energy through union with a specific deity, usually a celestial bodhisattva or Buddha, but also goddesses and gods with specific characteristics. The goal is to fully realize the wisdom of the individual deity by uniting with the deity. The practices may seem like worship, but the goal of absorbing the wisdom of the deity in order to achieve liberation clearly sets this practice apart from other devotional practices. Tibetan Buddhism is primarily tantric or Vajrayāna Buddhism and preserves many tantric texts. Their tradition claims that these esoteric secret texts were brought to Tibet in the eighth century CE by the great tantric master, Padmasambhava.

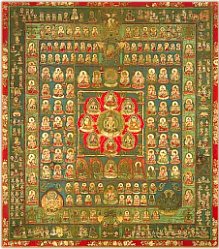

A mandala is a visual representation of the sacred. In the center of the mandala is the main deity or Buddha. Concentric rings around the center depict other beings and symbols that aid the meditator in concentration. The mandala in the image below depicts the “womb world” – the birthplace of Buddhas.