28 Historical Overview of Chinese Religions

Chinese religious culture developed more than 1200 years before the birth of Jesus, the founder of Christianity. Chinese history is divided into “dynasties” based on how long a particular ruling group held power. The “Warring States Period” in the fifth to third centuries BCE was a time of great disruption but also creative philosophic thought. These were unsettled times when people wondered about the best way to achieve harmony. Foundational works of Chinese thought: the Analects and the Laozi were produced during this period of disruption.

Confucius is regarded as the founder of Confucianism. His teachings are collected in a work called the Analects and are considered to be the foundation of Confucianism. The Laozi is an anthology of writings from many different teachers that is the source of the tradition called Daoism. The Analects and the Laozi offered different solutions for government and human development, but they accepted fundamental ideas about the cosmos and humanity that had developed during earlier centuries.

Since the ancient views on the order and nature of the universe are fundamental to both Confucianism and Daoism, we will begin with the Cosmology of Chinese Religion before describing the historical development of Confucianism and Daoism.

Cosmology: Early Chinese Worldview

By the 5th century BCE, Chinese culture had a developed a system of thought that saw the natural universe as a set of dynamic relationships. There was no idea of a single creator or a god who directed events on earth. Instead, the world could be described as a balance of different forces that operated according to impersonal and reciprocal laws.

Naturalistic Universe

Ancient Chinese believed in the regularity of the cosmos and that the world operates according to natural law. In the ancient religious culture there was no single thing, person, or divine being that gave the law and maintained it. The natural law of the universe was viewed as impersonal, like the laws of physics.

Three natural laws or principles were established in ancient Chinese thought:

- Natural processes operate in cycles. For example, night follows day, Spring follows Winter, and so on.

- All things grow and decline. For example, plants emerge in the Spring, flourish in the Summer, and die back in the Fall. Another example is the moon that appears in different phases during the month from a full round moon to no moon visible in the sky.

- Opposites are necessary and complementary. Night and day are opposite, but interdependent. Night yields when the daytime becomes stronger. Cycles of growth and decline are a fundamental principle of Chinese thought.

Interdependence of opposites: Yin and Yang

The diagram at the beginning of this chapter symbolizes the two primary opposites in the Chinese view of the natural world. The white side represents yang, or positive energy. The dark side represents yin, or passive energy. Notice that in the black side there is a small circle of white, and in the white side there is a small circle of black. These smaller dots within a larger field of their opposites represent the beginning of change. In the yang or positive, bright energy there is a seed of dark, passive energy. Within the darkness and passive side there is a seed of light and active energy.

In Chinese thought, a polarity of positive and negative, referred to as YIN and YANG, is part of its metaphysics. Yin means the passive force, yang means the active force. In this system, the world is not in a struggle of good and evil. Instead, the universe is a dynamic of the essential activities of growth and decline.

Heaven

Ancient Chinese people had a vague notion of a ruler in heaven which they called Di or Shangdi, “The great Di”. Shangdi is not a creator god. Instead, the Chinese conceived of Shangdi as a kind of judge.

This high judge was later called “tian” or heaven. Heaven was thought to be interested in human society, giving legitimacy to earthly rulers. A king or emperor could claim that his right to rule had been approved by heaven. This approval came to be known as the mandate of heaven. Heaven might withdraw its support of the ruler if he did not rule properly. Natural disasters outside of human control could be interpreted as the withdrawal of Heaven’s support, the mandate of heaven, from a ruler. It was also possible to lose the mandate of heaven through human agency, for example when a rival king or a popular uprising led to a king’s loss of power. In this case, the popular uprising of the usurper was said to have enacted the will of heaven.

Humans were never set apart from the natural world. Everything was believed to be integrated. Therefore, humans could look at the signs in the natural world to find out whether their own actions were in accord with heaven’s will. The interactions of people affected nature; and nature responded to the actions of people.

The Dao or “Way”

The Dao means a way of being that is in harmony with the way things are. Heaven itself must follow the Dao. In Chinese culture the Dao can mean both harmony with the yin and yang of the universe, and harmony with one’s place in social and familial roles. There are two styles of understanding “the way” in Chinese thought: First, the Dao is a norm or approved way of acting. The Dao is expressed through ethical and religious actions that are embedded in human society and family life. Second, the Dao is the regular operation of the universe: the way things are. Being in harmony with the movement of yin and yang expresses this idea of Dao. Yin and Yang come from the Dao: they are how we perceive the Dao acting in the world.

In Chinese thought, the Dao is fundamental, the origin. Yin and yang come from the Dao. Heaven follows the Dao through the operation of yin and yang:

- DAO ==> YIN / YANG ==> HEAVEN

Humans cannot directly perceive the Dao, but they can understand it through the alternation of yin and yang that they see in the natural world.

Supernatural Beings and Ancestor Veneration

There were also many supernatural powers and greater and lesser deities. These spiritual beings, although invisible, were considered to be quite real and able to affect human beings in positive or negative ways. Harmful spirits could emerge from people who had died violently or who felt that their funeral services and memorials had not been properly done. Such unhappy spirits would try to take revenge on living people. Various means such as charms, the use of mediums, and firecrackers were used to communicate with the spirits or scare them off. In contrast, ancestors who had been treated well were considered to be a source of good fortune and benefits.

There are many deities in Chinese religious and cultural traditions. Villages and towns honor their particular earth deity, the Tudi Gong, in seasonal festivals held in Spring and Fall. The earth deity has the duty to ensure the prosperity of the region, but if he fails the villagers may oust him in favor of another deity who is viewed as having more power. The documentary film, “Taoism, a Question of Balance” produced by the BBC contains footage of a village festival honoring the earth deity. The festival includes a procession of the deity through the village, accompanied by musicians and offerings.

The three immortals of Happiness, Prosperity, and Longevity or Fulushou appeal to the desire for a good life. These “immortals” were originally humans who were particularly talented or good to others in life. East Asian cultures typically honor such extraordinary humans after death as a type of deity.

- Shouxing, Immortal of Longevity Shouxing appears as a bearded old man, leaning on a stick and holding a peach, the symbol of longevity. In addition to the human spirits, Chinese religious beliefs included the spirits of animals, plants, and even stones.

- Luxing, Immortal of Prosperity Luxing appears as an elite Chinese scholar with a winged cap on his head. He is the focus of prayers from people who are studying to pass the imperial exams, a gateway to propsperity in life.

- Fuxing, Immortal of Happiness. Fuxing holds a baby with a kindly expression on his face.Ancestor veneration means to respect one’s own deceased parents and the ancestors of one’s family. This respect is shown through periodic rituals and memorials, but also by following the wishes of the deceased parent. The ritual practices required at the death of a parent were extensive and involved a withdrawal from usual social activities during the mourning period which might last as long as 3 years.Respecting your parents is called filial piety. It includes sincerity and obedience during their lifetime, proper funeral rites, and periodic memorial services after their death.

Divination

Divination was an important part of Chinese religious culture from at least 1200 BCE. There are two basic goals of divination. One goal, usually associated with the state, is to understand both the natural and supernatural forces of a particular situation in order to know how to act in harmony with these forces. A different goal involves the family and is aimed at filial piety. This kind of divination is to find out the needs of a deceased parent in order to perform the proper rituals. Neither of these types of divination is about knowing the future. Both address present conditions in order to understand how to act. In Chinese religion, once you know how to act in harmony with the Dao in the present, your future life will be successful.

In the first type of divination, usually done by religious specialists who could understand the signs, tortoise shells were heated then plunged into cold water. The specialist then “read” the cracks on the surface to understand the conditions of yin and yang and decide on a course of action. The second type of divination is usually performed by a religious specialist called a shaman, one who can contact the spirits through trance.

One of the most ancient texts of divination is the Book of Changes (Yijing). The Book of Changes lists 64 six-line diagrams called hexagrams and comments on their meaning. The top three lines refer to conditions above (heaven) and the lower three lines refer to conditions on earth. For example, the following hexagram, the first one in the Book of Changes is called qian, which means the Creative or Heaven.

- _______

- _______

- _______

- _______

- _______

- _______

There are three solid lines in the upper part of the hexagram (lines 1-3); and three solid lines in the lower part (lines 4-6). The solid lines in any hexagram are interpreted as yang, so this hexagram is made up entirely of yang energy or positive, active energy. If you remember the symbol of yin (darkness) and yang (light) at the beginning of this chapter, a completely yang situation will soon change towards yin because it has a seed of yin or darkness within it.

The 64 hexagrams of the Book of Changes are believed to date to the Shang Dynasty (1200-1059 BCE), but the book includes later commentaries on each diagram that developed during the Chou dynasty (1059 BCE – 249 BCE). A skilled person uses yarrow sticks, something like straw only more solid and straight, to determine which of the 64 hexagrams will guide action on a particular problem. The commentaries help the person interpret the meaning of the hexagram. The purpose of the divination is not to find out what will happen in the future, but to understand how to act in the present.

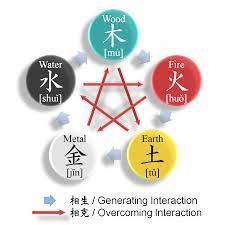

In addition to the polar opposites of active (yang) and passive (yin), the ancient Chinese classified all things into five elements or functions of water, fire, wood, metal, and air that allowed the Chinese to evaluate each phenomena. The elements could also affect one another; for example, water can overcome fire; fire can overcome wood, and so on. In making important decisions, the interactions between the elements were considered. The following diagram of the five elements shows you the dynamics between them. The blue arrows show a progression; the red arrows show the patterns of dominance. For example, the blue arrow from wood to fire shows that wood stimulates interaction with fire. The red arrow between water and fire demonstrates that water can put fire out.

These two systems of classification, yin and yang and the five elements, are based on the actions of the natural world which can be observed. Notice that there is no supernatural being that directs the actions of the natural world or human activity. Instead, the Dao is revealed through the dynamic of yin and yang and the interaction of the five elements. Interpreting these signs of the natural world was a highly valued skill that helped people respond to conditions as they are.

Sacrifices and Rituals

From at least 1000 BCE, Chinese people regarded the world as an interaction between active and passive forces. These forces could be interpreted by “reading” the natural world through divination. Human activities affected heaven, which could give their support to a ruler through the mandate of heaven, or withdraw it if he did not lead the people in ways that conformed with the Dao. The Chinese worldview, therefore, was one in which human actions had consequences, but also it was important to read the signs of nature properly to understand the best course of action.

Rituals and sacrifice were an important element in the ancient period. There are records of ritual procedures and historical accounts of rituals going back to the 12th century BCE. Archaeological evidence from inscriptions on bronze vessels (ding) also testifies to sacrificial practices.

We know from these inscriptions on bronze bowls and other objects that the sacrifices were grand social occasions that reflected the social hierarchy. The sacrificial food was prepared as a feast. After offering to the spirits, the rest of the assembly would eat, starting with the highest ranked members, with each lower rank receiving the leftovers from the higher rank until finally the ordinary people ate. As you think about this, notice that the entire community is involved, with the upper ranks making sure not to eat too much so that the lower ranks will be able to share. The lower ranks waited their turn to eat. This ritual procedure shows how important it was to know your duty to your rank and to care for those who are lower in the ranking.

The Shanghai museum has the form of a ding. This is a good example of the effect of religious material objects on the culture as a whole. Although people may not be always aware of its effect, the repetition of the shape in various contexts shows the power of the ding as a cultural icon.

Three Religious Masters

In the next two sections we will investigate the teachings of Confucius, founder of Confucianism; and the Laozi, an important figure in Daoism. These are the indigenous religions of China: they started in the ancient pre-historic periods of Chinese culture. But there is another figure of importance in Chinese history: the Buddha. Buddhism first came to China in the first century CE, brought by traders and traveling monks on the Silk Route which connected China with cultures to the west. Although regarded as a “foreign” religion, Buddhism soon became embedded in Chinese society and culture and established powerful temples and intellectual development.

These “three religions” of China are depicted in paintings. The adult male dressed in court clothing with a hat represents Confucianism; the adult male dressed in flowing robes represents Buddhism; and the baby in the arms of Confucius represents Laozi, the “old baby” of Daoism.