72 Introduction

The Nahua of Central Mexico

This chapter highlights the religious practices of a particular Native American group known as the Nahua. At the broadest level, Nahua refers to anyone who speaks the language of Nahuatl. Nahuatl was widely spoken in central Mexico at the time of the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City) c. 1519-1521 CE. Spanish conquistadores like Hernán Cortés encountered Nahuatl speakers such as the Aztec emperor Montezuma II. Though the Spanish may have toppled the Aztecs by 1521, they could not dislodge the language of Nahuatl nor the customs of Nahua peoples. While Aztec refers to an Indigenous group that spoke Nahuatl, many other groups of Native peoples used the Nahuatl language. In fact, Nahuatl remains in use today throughout central Mexico.

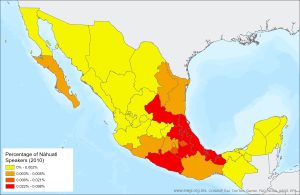

Though in decline, Nahuatl remains the native tongue for Nahuas in Veracruz, Puebla, Guerrero, and Oaxaca.

At present, there are approximately 1.7 million speakers of Nahuatl, most of whom reside in villages in central Mexico. Nahua villages of the twenty-first century CE display remarkable continuities from the sixteenth century CE, particularly in the cosmological importance of duality in all things. Before delving further into ancient and modern Nahua rituals, however, an additional point on conquest and history should be made.

The year 1492 CE proved to be a pivotal moment for the history of the Americas. The voyages of Christopher Columbus brought Europeans face-to-face with the Indigenous polities of the New World. Peoples such as the Taino (Caribbean), the Nahua (Mexico), and the Inca (Peru) did not anticipate this European incursion. However, arrive Europeans did. It took a while for Europeans to realize they had stumbled upon two new continents, eventually labeled North America and South America.

Although Christopher Columbus landed in the (modern-day) Bahamas on October 12, 1492 CE, he lived and died (c. 1506 CE) thinking he had successfully reached Asia. Many Europeans in Columbus’s day were eager to establish trade with India and China for tasty spices and artisanal fabrics, ceramics, and jewelry. When Columbus left the Canary Islands in the Atlantic and sailed toward the west, he wanted to land somewhere in Asia. For this reason, Columbus erroneously called the Native peoples of the Caribbean “Indians,” meaning people from India.

Europeans later learned Columbus had not reached Asia, but the term “Indian” (indio in Spanish) remained. Rather than use ethnic names like Taino, Mexica, Apache, Comanche, etc., Europeans often applied “Indian,” thereby flattening ethnic diversity into a superficially homogenous whole. Many successful European colonies developed from the “West Indies,” referring to the islands in the Caribbean. This history of conquest helped to popularize terms like “indio” in Spanish and Portuguese or “Indian” in English. While the term “Indian” remains in use today, we should acknowledge its inaccurate initial application by European explorers and settlers who came to North and South America without seeking the consent of the Indigenous peoples.