20 New Interpretations of Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna

Mahāyāna Buddhism

Mahāyāna scriptures appeared in approximately 100 BCE. These scriptures reinterpret ideas from the earlier tradition. There are four main Mahāyāna ideas that expand Buddhist teachings and the potential to become a Buddha.

All things are empty of self-identity and permanence

Around 100 BCE, a group of scriptures called Perfection of Wisdom explained that all things are without a permanent essence and are therefore interdependent. For example, physical forms appear to be solid, but they are temporary, and are defined by other things. Modern physics explains the physical universe as forces that interact: a table is a collection of atoms that temporarily are attracted to each other but eventually will disperse. Similarly, “emptiness” refers to this interdependence. If we apply the concept of emptiness to the opposites of samsara and nirvana, then we see how they are interdependent. Without samsara there is no nirvana!

How is this a religious idea? Emptiness changes your idea of reality: it is no longer a permanent, stable thing but is constantly changing. The concept of emptiness changes our fixed ideas about the world and teaches us to be flexible and interactive. The idea of emptiness is also applied to ethics in the Perfection of Wisdom texts. They suggest that being aware of emptiness with every action you take, you can become free of karma. Not thinking of the gift, the giver, or the receiver, you simply give without attachment to any ideas about it. The emptiness doctrine is an important part of Zen Buddhist meditation and training.

Buddha Nature

Another important idea in Mahāyāna was the idea that all beings have Buddha Nature, the potential to become a Buddha. Although we have this capacity to become enlightened, we do not fully realize enlightenment without Buddhist practice and training. The teaching of Buddha nature addresses the question of why beings strive toward enlightenment by suggesting that it is part of our nature.

The teaching of Buddha nature is similar to another Buddhist teaching that our minds are inherently pure, but interaction with the senses stimulate our past habits, our karma that leads us into impure actions like acting in anger or being greedy. Both Buddha Nature and the inherent purity of mind point to the idea in Buddhism that enlightenment is possible for all beings.

The Bodhisattva Path and Goal

In Mahāyāna scriptures there is a new emphasis on the bodhisattva path. The goal in early Buddhism was to reach nirvana, a state free of the effects of greed, hatred and delusion. People who achieved this were called arhat: a person who had listened to the teaching of the Buddha and put it into practice, finally realizing its truth. In Mahāyāna scriptures, however, the goal shifts toward becoming a Buddha, a fully awakened being whose wisdom and knowledge goes beyond simply solving the problem of karma and rebirth. Mahāyāna Buddhism teaches that a “bodhisattva” is anyone who develops the aspiration to become a Buddha and makes that commitment. This aspiration is called bodhicitta, which literally means “thought of enlightenment” (bodhi= enlightenment; and citta = thought). It is an important step that comes after years of meditation and study.

The bodhisattva is also one who vows to help other beings reach enlightenment while working toward enlightenment. The bodhisattva vow is to remain in samsara until all beings reach nirvana. This idea changed how people understood the path of Buddhist practice. Many lifetimes of helping others meant that bodhisattvas accumulated great merit or spiritual power which they may give away or dedicate to others. This idea of many lifetimes dedicated to helping others leads to the idea of celestial bodhisattvas, beings whose wisdom and compassion are so highly developed that they have special powers to help other beings. Celestial bodhisattvas become objects of prayer and worship. For example, the bodhisattva Avalokitesvara is known as the bodhisattva of compassion. Those who are in difficulties may call on Avalokitesvara for help. In the image below the bodhisattva of compassion is in an open pose, ready to leap into action if anyone needs him. On his chest he wears jewelry and on his head is a headress, both symbols of his connection with the ordinary life of beings in samsara.

Eternal Buddhas and Buddha Lands

Earlier in the chapter we learned that the Buddha himself explained that a Buddha manifests the Dharma or teaching. The Dharma is not unique to him: other Buddhas have appeared in the world.

The Lotus Sutra, an early Mahāyāna scripture, takes this idea one step farther, explaining that Sakyamuni appeared in the world as a human in order to demonstrate the Dharma. The demonstration included the struggle for enlightenment, his forty years of teaching, and his parinirvana. These events were all the Buddha’s “skillful means” to teach people about the possibility of nirvana. His body on earth is a “manifestation body” to teach others. But in fact, the scripture states, he is really the “body of the Dharma” which has no physical form. From time to time a Buddha appears in the world to revive people’s understanding of the Dharma.

A Buddha may also appear in his own Buddha land which is created from the vows he takes as a bodhisattva. The Buddha land is considered to be a “body of enjoyment” that concentrates all the good merit from his enlightenment.

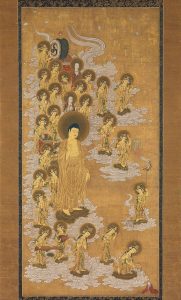

The Pure Land scriptures describe how Amitabha Buddha, when he was a bodhisattva, learned about all the different kinds of Buddha lands and decided that when he was enlightened, his Buddha land would contain the best characteristics of Buddha lands. To be reborn in his Pure Land, a person only needs to have faith in Amitabha while reciting the name “Amitabha Buddha”. Although pleasant, the Pure Land of Amitabha Buddha is not technically a heaven. Rebirth in this pure land brings beings closer to the Dharma so that they will reach nirvana. Images of Amitabha Buddha in Japan often show Amitabha descending to greet the faithful at the moment of death. In the following image, Amitabha is the large figure, surrounded by bodhisattvas. The person in the lower right of the painting is the newly deceased believer.

Schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism in East Asia

Different schools of Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in China and spread to Korea, Japan, and later to the West. Since China received a great variety of different scriptures from early Buddhism through tantric texts in the eighth century, these “schools” or scriptural lineages at first were identified by the scripture that they held in highest regard. The rules of the monastery and the meditation practice was fairly uniform, but philosophically, different schools adopted the ideas of their main scriptures.

Three of the most important trends in East Asian Buddhist schools are:

- The Tiantai lineage, focused on the Lotus Sutra.

- The Pure Land lineage, focused on three Pure Land Sutras.

- The Chan lineage which did not take one single scripture as its focus. Instead, they regarded the enlightened master as their guide. The Chan school, or Zen as it is known in Japan, eventually developed their own literature of stories of people awakening to Buddhist truths.

Vajrayāna Buddhism

In terms of doctrine, Vajrayāna Buddhism is based on the Mahāyāna principles outlined above. But its approach to practice is quite different. Vajrayāna is also called Tantric Buddhism because it developed at a time in India when the use of tantric spells and practices was growing. Tantras are esoteric formulas: you must learn them directly from a teacher. The knowledge of tantras cannot be learned in a book. Buddhists adopted these new practices and applied them to Mahayāna Buddhist doctrines. So it is best to think of Vajrayāna as a form of Buddhism that uses esoteric methods of practice. This form of Buddhist practice developed in the seventh century and flourished in Tibet where it was imported by Indian teachers and developed in monastic institutions. It requires great dedication and concentration, but is considered to be an effective path to liberation.

Tantric practices are divided into four types: Action, performance, yoga, and advanced yoga. A person must first receive consecration from a teacher before beginning a tantric practice. Consecration is a ritual in which the person is dedicated to the practice. Once a person has performed the ritual of dedication then the teacher will teach the tantric practice. The first levels of tantra are devotional practices that involve performing rituals and devotions to gods, goddesses, and bodhisattva figures. The tantras involve body, speech and mind by employing visualizations, chants, and rituals. In higher levels of tantric practice, the practitioner creates a strong identification and visualization of a chosen deity or Buddha in order to embody the wisdom of that being. In this way, the individual transforms his or her identity through visualization and realization.