8 Seven Dimensions of Religion in Hinduism

Narrative and Experience in Hinduism

Hinduism developed a broad range of literature, beginning with the chanted hymns of the Vedas, the dialogues between master and disciple in the Upanishads, to the epic tales of the Mahabharata and the Ramayana and the legends and mythology of the Puranas.

Sruti and Smrti

Hinduism makes a clear distinction between literature that is considered to have a supernatural origin and literature that preserves the living memory of the culture. The Vedas and Upanishads are classified as sruti, that which is heard. These works are believed to be the knowledge gained by sages or rishi, people who accessed this knowledge through concentration and mental powers. They were believed to have “heard” the hymns and instructions for the ritual. Sruti literature was primarily oral and memorized. Learning the hymns and rituals was mainly through close work with a teacher, and this knowledge was restricted to certain classes of people. Only those born in the priestly caste were permitted to perform rituals.

Smrti means that which is remembered. This category includes collections of stories, legends, law, and philosophic works. Srmti literature could be added to, changed, and developed freely. For that reason, it has had a great impact on the culture of Hinduism as it is flexible and can be told in many different ways. For example, parts of the great epics of the Mahabharata and Ramayana were presented in movies and television shows as these became popular ways of telling the tale.

The dimension of Narrative is therefore closely linked with the dimension of Experience in Hinduism. Through narrative, one experiences reverence for the gods and for the unity of the universe as Brahman.

Vedas

The Vedas are a collection of hymns to deities of the sky, atmosphere and earth. The Vedas also include songs and ritual chants that are done during the sacrifice. The hymns are not exactly narratives, but they often include a description of what the god did in the past. For example, a hymn to Indra, the great warrior and protector who defeated the serpent, Vritra declares:

Now I shall proclaim the mighty deeds of Indra, those foremost deeds that he, the wielder of the mace, has performed. He smashed the serpent. He released the waters. He split the sides of the mountains. He smashed the serpent, which was resting on the mountain; for him Fashioner had fashioned a mace [club] that shone like the sun. Like lowing cattle, the waters, streaming out, rushed straight to the sea. (Embree 1988, 12)

It is a myth of the great deeds of Indra and it contains a lot of physical detail that makes the story vivid. But it does not contain any dialogue, and it is not about human life. It is a hymn of praise of mythical, supernatural actions and the character of Indra. The hymn is declarative, not conversational.

There are four Veda, each with its own function:

- Rig Veda: the oldest Veda, a collection of 1000 hymns

- Sama Veda: verses for singing during a ritual

- Yajur Veda: the liturgy spoken by a priest as he performs actions during the ritual

- Atharva Veda: incantations for practical purposes, such as healing sickness or easing childbirth.

There were three basic types of Brahmanic ritual:

- Offerings to the gods to sustain them.

- Asking the gods for benefits.

- Praising the gods to sustain the relationship between humanity and the gods.

The Aryan gods or deva represented functions of the natural world. They fall into three types: those of the sky, the atmosphere and the earth. There were many gods in each of the three classifications, but the most important ones were Varuna, Indra, Agni and Soma.

Varuna is the sky god. His role is to preserve cosmic order. When humans fall into error Varuna will punish them by bringing on sickness. Cosmic order is an impersonal idea, it is the way of things. Hymns to Varuna express the relationship between cosmic and moral order.

Indra is the god of the atmosphere, a storm god. A famous myth of Indra defeating the snake-demon Vritra who had blocked the sun and the rain, made Indra famous as a warrior, one who saved humanity. Indra is fond of the intoxicating drink soma and is often shown as excited, waving his thunderbolt.

Agni is an earthly god, the god of fire. He is the central god in the fire sacrifice. Agni accepts the offerings of humans and brings them to the gods through the heat and smoke of the fire.

Soma is an earthly god, the god of the intoxicating drink made from plants. By drinking soma, humans could enter the kind of ecstatic state that allowed them to experience the divine. Soma, therefore, is both a god and a sacrifice at the same time.

The two earthly gods, Agni and Soma, are somewhat under the control of humans. The three types of ritual sustain the gods materially and strengthen the ties between humanity and the gods through asking for benefits and through praise of the gods. Human actions of making fire, chanting the sacred sounds, and creating soma out of a plant all contributed to the properly done ritual. Only then does the ritual have the power to influence the gods and call on their power. This is a key point in Vedic religion: that humans share in sacred power through their actions. By making offerings to the gods they help to sustain the gods. In this sense, they are partners with the gods in maintaining the order of the universe.

The later hymns of the Rig Veda question the underlying unity of the universe. They ask, if the gods maintain order, then order must have existed before the gods themselves. Ideas about how the universe might have been created began to appear. The most important idea is that the sacrifice itself is the creative power of the universe.

This creative power of ritual is expressed in the Rig Veda Hymn to the Person. The hymn first describes a primordial great man or Purusha, who extends beyond the limits of the universe. It then describes how the gods and the rishi or sages sacrificed the Purusha in order to create the world. The various parts of the body of Purusha are divided up to make the universe. Thus the natural order of the universe is dependent on a sacrifice that took place in a cosmic time. Humans, gods and all aspects of the universe came out of this primordial man, the Purusha.

The Upanishads: sitting at the feet of the teacher

The Upanishads were first composed from 600 BCE through 100 BCE. Upanishad means to sit nearby, a description of the relationship between one who teaches the sacred sounds and rituals and one who learns. Many of the Upanishads are written as dialogues between master and disciple, or a priestly father and his son since the knowledge of the ritual was passed down from father to son.

The Upanishads played a pivotal role in transforming the Brahmanic religion of ritual sacrifice. In the early period of Upanishad composition, from the sixth to the fifth century BCE, ideas in the Upanishads influenced the development of Buddhism and Jainism. These two religions, however, rejected the authority of the Veda.

Two important concepts in the early Upanishads shifted the basis of religious practice from the Brahmanical ritual sacrifice. The first was the concept of karma or action, and its effect on the future, including rebirth. The second was the idea of the atman, a greater Self within each person and its relation to the Brahman, the unitary reality of the universe.

In the Upanishads, the construction of a self through good works and properly done ritual is viewed as merely temporary. Continual birth and rebirth are seen as a negative, uncertain process. Although good actions might lead to heaven, even heaven is impermanent and the self will be reborn elsewhere once the effect of action (karma) has worn off. The Upanishads propose the idea that in order to gain liberation from the round of birth and death, one must gain knowledge of the true reality of the universe. The Vedic ritual system of Brahmanism is gradually superseded by a search for the knowledge of the unitary principle of the universe, Brahman.

True knowledge in the Upanishads is defined as the identification of the greater self of the individual, the atman, with the Brahman, the principle of the universe. The Upanishads shift toward various practices of mental and physical control. These practices fall under the general category of yoga which means “union.” In order to realize the underlying unity of the individual and the universe, a person withdraws from society to practice control of physical needs and to develop mental concentration. These practices came to be known as jnana yoga, or “knowledge yoga.” By 200 CE Patanjali, a teacher in the Upanishad tradition, had composed the Yoga Sutras which explained eight aspects of yogic practice.

Narrative in the Upanishads

The Upanishads contain similar descriptions of mythical events, but it introduces dialogues between master and a disciple. These short narratives have a doctrinal point. The dialogues also show the warm, trusting relationship between them. For example, here is a famous dialogue between Uddalaka (the master) and his son Svetaketu (the disciple). The topic is the atman and the Brahman:

[Master says]: Bring a banyan fruit.

[Disciple replies]: Here it is, sir.

Cut it up.

I have cut it up, sir.

What do you see there?

“These quite tiny seeds, sir.

Now, take one of them and cut it up.

I’ve cut one up, sir.

What do you see there?

Nothing, sir.

The master told the disciple: This finest essence here, that constitutes the self of this whole world; that is the truth; that is the self (atman). And that’s how you are, Svetaketu.

(Chandogya Upanishad, 6.12.2; Olivelle 1996, 154)

In this dialogue, the master uses an ordinary fruit, the banyan, a kind of fig, to illustrate the relation between atman and Brahman. The nothing in the center of the seed is the essence of life: what makes it grow. Invisible, but real, this essence is indispensable. It is the same as the invisible principle of reality, Brahman.

Epic Literature

Two important epic texts became prominent around 200 BCE: the Mahabharata with its famous sub-section, the Bhagavad Gita; and the Ramayana. The Mahabharata and Ramayana are still popular in modern Hinduism. Epic tales are classified as things that are remembered and are understood to be composed by humans. But many consider them to be equivalent to scripture because of their depiction of moral dilemmas, courage, and wisdom.

The epics weave together much older materials, some of which may have been preserved since the Indus Valley Civilization period. They are a good example of the combination of different cultural traditions: the Vedic culture and popular religious values.

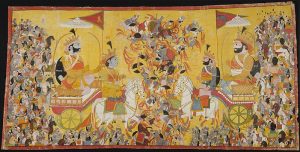

The two epics are both about epic battles, warriors and kings. They provide descriptions and narratives for important deities that come to dominate Hinduism. This section describes the different deities associated with each of the texts.

Mahabharata

The Mahabharata is an epic poem whose core may date back to the fifth century BCE. Various sources, including the Vedas and other literature were absorbed into the Mahabharata until it became a large collection of literature that amounted to almost 100,000 verses.

The story of the Mahabharata begins with Siva, a god whose form and identity closely resembles the ancient horned god of the Indus Valley Civilization seals. Siva appears in the Mahabharata as a more fully developed figure, portrayed as a mountain ascetic, one who practices control of the senses and desires in order to gain spiritual power. He uses this power to help those who pray to him. He is also described as a great creator. His symbol is the phallus or erect penis (lingam) which symbolizes fertility. His creator role resembles the Indus Valley seal of the horned god, surrounded by his creatures, the animals. The two opposites of celibate ascetic and the creative power of the lingam give Siva a double identity.

Vishnu, a god closely associated with the Vedic sacrifice, is a major figure in the Mahabharata. His identity is a combination of both Vedic sources and stories outside of the Vedic tradition that had gained popularity in the second century BCE. These two kinds of sources can be traced through the various names associated with Vishnu and the stories themselves. The text merges the priestly and popular sources to create a wide range of qualities and forms for Vishnu, making him an attractive focus of worship for various groups of people. The Vedic scriptures provided religious teachings for the figure of Vishnu.

Narrative in the Bhagavad Gita

The Bhagavad Gita is a subsection of the Mahabharata epic poem that contains a long discussion of morality and duty. In the story, the throne has been stolen by one division of the family of the rightful king, creating disorder that must be corrected. Arjuna, the rightful heir to the throne and a warrior, is very upset by the idea of having to fight and even kill his cousins to win the throne. He believes that such a sin would cause karmic harm. But it is his duty to fight, so how can he resolve this conflict?

The moral dilemma set up in this epic tale has mainly to do with action (karma). How does a person act in the world when all the choices appear to be bad ones? The narrative focuses on a dialogue between Arjuna and his charioteer, Krishna. It is the night before the crucial battle. Arjuna is so disturbed that he lays down his arms. This is a crisis of confidence. It needs immediate action if Arjuna is to fight tomorrow, win back the kingdom, and restore order. If he refuses to fight he cannot fulfill his dharma.

Krishna explains the three yogas

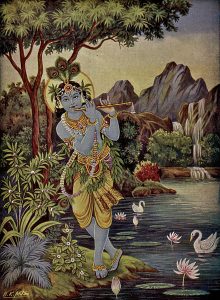

The solution to the dilemma is taught to Arjuna by his charioteer, Krishna. Krishna is actually an avatar of Vishnu. As the supreme god, Vishnu has many different forms in the world. An avatar is an appearance or manifestation of the god Vishnu in visible form for the purpose of teaching human beings. Krishna, as the avatar of Vishnu, teaches Arjuna the highest truths.

Krishna explains two ways that Arjuna can overcome his hesitation. The first way is through jnana yoga, the way to liberation through knowledge. He argues that Arjuna’s understanding of killing is wrong. Since everyone must die and be reborn, thinking that you are killing is a wrong view of the actual situation. Krishna explains that just as the embodied soul in this life continuously passes from boyhood to youth to old age, the soul similarly passes into another body at death. The experiences of happiness or sorrow arise from sense perception, so the wise person must learn to tolerate them without being disturbed.

Second, Krishna argues that it is Arjuna’s duty to fight. If he does not fulfill his Dharma, then no one will respect him, and he will be remembered as someone who let everyone down. Krishna’s argument goes deeper than this later in the text. Krishna explains karma yoga as the way to liberation through action. Since a warrior’s duty involves killing, then performing this duty completely with no thought of reward can lead to liberation.

Krishna begins with jnana yoga, teaching Arjuna the path of wisdom in which a person realizes that the atman, the indestructible part of one’s being is identical with Brahman, the principle of the universe. Krishna then argues that a person may fulfill spiritual goals through action or karma yoga. By completely fulfilling one’s karmic role with nothing held back, a person achieves liberation. Finally, when Vishnu then reveals Himself through Krishna, we see the power of devotion or bhakti yoga.

These three paths to spiritual knowledge: jnana yoga, karma yoga, and bhakti yoga are all explained in the text of the Bhagavad Gita through the dramatic situation of a warrior who hesitates to fight. Doctrinal teachings are woven throughout the narrative, making these ideas about the Hindu path to liberation more relevant to their lives.

Ramayana

The Ramayana is also a tale of a lost kingship and battles to restore order. The hero of the story, Rama, faces many challenges throughout the story. Each time he chooses the right path to fulfill his Dharma. His behavior sets the model of an ideal man: honest, persistent, ruling as a good king. His wife, Sita, is also a model of the ideal woman: compliant, faithful and pure in her behavior. But there are many difficulties along the way.

Rama is depicted in the epic poem, the Ramayana, as the oldest of three princes who is heir to the throne. When it is time for him to take the throne, his step-mother reminds the king that he promised her that her son would be the ruler, not Rama. The king upholds his word and banishes Rama and his wife Sita to the forest. In the forest Sita is captured by the demon Ravana and taken away to an island. Rama and the monkey god, Hanuman, attack the island and rescue Sita from the demon. They have her undergo a fire ritual to prove her faithfulness. Agni, the fire god, protects her, proving her faithfulness while she was held captive. Rama regains the kingdom as the rightful king.

However, rumors that Sita must have submitted to the demon persist in the kingdom, so Rama gives in to public opinion and exiles Sita to the forest. There she gives birth to their children and raises them to praise their father, Rama as the perfect ruler and perfect man. Years later at a festival, the children attend and recite the Ramayana, bringing Rama to tears. He brings Sita back to the kingdom, but continues to doubt her purity. In a final test, Sita asks mother earth to swallow her up if she has been faithful to Rama. Sita, the faithful wife, is taken by the earth. Rama now learns that he is in fact an avatar of the god Vishnu.

The Ramayana is a somewhat ambivalent tale. Although the hero of the epic, Rama, believes that he is a human throughout the story, at the end of the story he learns that he is in fact an avatar of the god Vishnu. All the actions which he believed that he took as a man were in fact accomplished as Rama, the avatar of Vishnu.

These two epic tales of Rama and Krishna as an avatar of Vishnu set the stage for the next phase of Hinduism in which religious identity was based on which deity one worshiped.

Puranas c. 380 CE – 600 CE

By the third century CE, the form and content of the Mahabharata and Ramayana were complete. New theistic movements developed that centered on Vishnu and Siva. Those who focused on Vishnu were called Vaishnavites; those who focused on Siva were called Saivites.

Theistic movements developed through a new form of literature called the Puranas. Also written in verse form, their purpose was to transmit ancient materials that were outside of the Vedic tradition. The Puranas deal with five themes:

- Creation of the universe

- Re-creation of the universe after periodic destruction

- Genealogy of gods and sages

- Ages of the world and rulers

- Genealogy of kings

The Puranas are the main source of teachings for theistic Hinduism. They provide stories of the gods and their avatars that provide believers with a backstory and a focus for their devotion. For example, the Vishnu Purana describes the boyhood of Krishna as a cowherd. Some stories show Krishna having divine powers, other stories show him as a young man, playing with the cowgirls and seducing them. These imaginative stories help devotees to feel close to Krishna and to fall in love with him.

Theistic movements developed into the full practice of bhakti yoga, the path of devotion. The bhakti movement received a boost in 320 CE when a new ruling family, the Gupta, began to actively support these movements. The Gupta referred to themselves as devotees of Krishna, and suggested that their reign represented Vishnu’s protection. The enthusiasm of the Guptas for devotional practice established theism as a state religion. They donated money to build temples, and their generosity was imitated by other wealthy donors.

Narrative in the Puranas: Bhagavata Purana

The Puranas are filled with long, detailed stories about the gods. Many of the stories fill in the gaps left by the epic tales. This is especially true of the avatars of Vishnu such as Krishna. If Krishna appears as a charioteer who guides Arjuna in the Bhagavad Gita as an avatar of Vishnu, then what was his boyhood like? Was he always divine? The Puranas answer questions like this.

The Bhagavata Purana describes Krishna as a young boy. Krishna is very playful and mischievous, letting the cows out and pulling their tails, and playing many tricks on people. In one incident, his mother, Yasodara tries to scold him, but finds instead a vision of the universe:

One day when Rama [not the avatar Rama] and the other little sons of the cowherds were playing, they reported to Krishna’s mother: Krishna has eaten dirt.

Yasodara took Krishna by the hand and scolded him for his own good, and she said to him seeing that his eyes were bewildered with fear, Naughty boy, why have you secretly eaten dirt? These boys, your friends, and your older brother say so.

Krishna said, Mother, I have not eaten. They are all lying. If you think they speak the truth, look at my mouth yourself.,br> Yasodara said, If that is the case, then open your mouth… She then saw in his mouth the whole eternal universe, and heaven, and the regions of the sky, and the orb of the earth with its mountains, islands, and oceans; she saw the wind, and the lightning, and the moon and stars…

(O’Flaherty 1975, 220)

The Purana goes on to describe all the things that Yasodara sees. Through this experience, Yasodara realizes that her son Krishna is a god, and her narrow ideas about being the mother of a child and wife of a husband are a delusion. Instead, there is only devotion to god. The god then lets her forget this vision and return to her life as before, but filled with love.

This dramatic story from the Bhagavata Purana illustrates a doctrinal point: that the world of the senses is an illusion, but that devotion to the god reveals the truth.